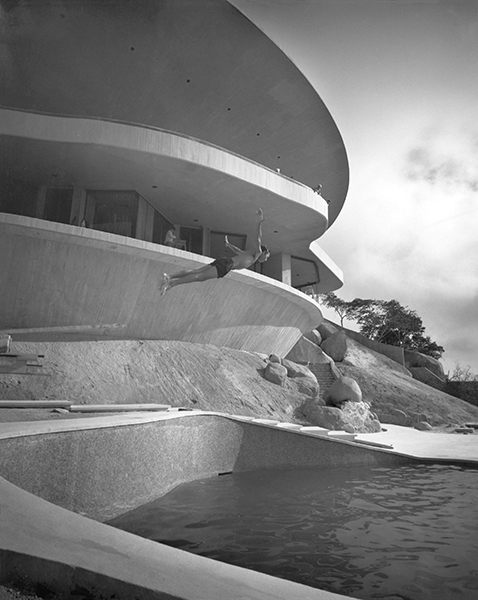

House at 131 Rocas, Jardines del Pedregal, Mexico City, designed by Francisco Artigas and Fernando Luna, 1966, illustrated in the book Francisco Artigas (1972). Roberto and Fernando Luna photo, © Roberto and Fernando Luna.

House at 131 Rocas, Jardines del Pedregal, Mexico City, designed by Francisco Artigas and Fernando Luna, 1966, illustrated in the book Francisco Artigas (1972). Roberto and Fernando Luna photo, © Roberto and Fernando Luna.

Design

Simpatico Modernism

NEARLY THE ENTIRE January 24, 1954 edition of the Los Angeles Times’s Home magazine—organized by the city’s preeminent architecture critic, Esther McCoy—was devoted to design emanating from Mexico. Dismissing stereotypes that cast the nation as a technological backwater, McCoy praised the advances made by companies like Industria Mueblera, proclaiming that its furniture had “as fine a finish as Swedish and Finnish chairs.” In her estimation, the Mexico City firm had perfected the balance of handwork and innovative machinery. One chair from a line by New York–based designer Edmond J. Spence, for example, combined electronically molded mahogany plywood with handwoven palm, a traditional material in Mexican seating.

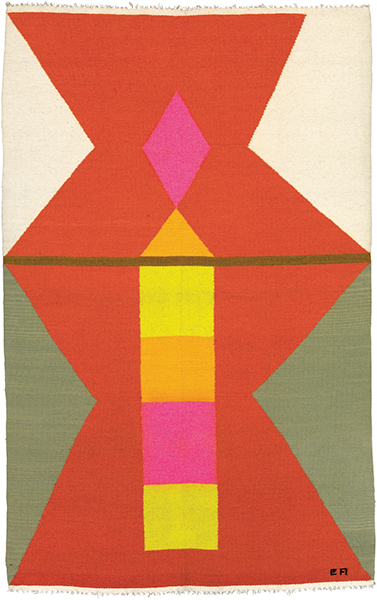

Launch Pad, tapestry by Evelyn Ackerman for ERA Industries, 1970. Collection of Jerome Ackerman, © ERA Industries/Evelyn Ackerman, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

The January 24 publication was one of several produced by McCoy, an active champion of Mexican modern architecture and design. An astute observer of the California scene, she clearly recognized that many of the same issues that galvanized Mexican designers, such as the blurring of indoor and outdoor spaces, the commingling of industrial and handmade goods, and the need for a new paradigm of modern single-family housing, would resonate with her readers at home. The exhibition Found in Translation: Design in California and Mexico, 1915–1985 delves into these connections and others. The histories and populations of these neighboring places are deeply intertwined. Their cultures remained linked even after the Mexican-American War, when Alta California became part of the United States.

Hanging light by Raul Angulo Coronel for Stoneware Designs, c. 1964. Collection of Michael and Mindy Hickman, Brian Forrest photo

Chaise longue by Po Shun Leong, 1971. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of Po Shun Leong, © Po Shun Leong, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Architects and designers invoked aspects of this shared past in their efforts to establish national and regional identities, often looking beyond political boundaries. In his designs for the 1915 Panama-California Exposition in San Diego, the East Coast–based architect Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue channeled the Churrigueresque churches of Taxco and Puebla rather than the more austere California missions, inventing a fantasy colonial history to match the grand visions of the city’s boosters. In the 1930s and 1940s, developers in Mexico City adopted design elements from the elaborate Spanish colonial revival mansions shown in Hollywood films and magazines to appeal to the aspirations of affluent clients. This hybrid style became known as colonial californiano. Historic structures also served as source material for architects who sought a regional interpretation of modernism. Irving Gill and Luis Barragán simplified, respectively, the forms of missions and monasteries down to their geometric essences, while Frank Lloyd Wright echoed the imposing mass of Mayan buildings in his Southern California homes.

Butaca chair by Clara Porset and Xavier Guerrero, designed c. 1940. This example was made in 1955–1956 for the Luis Barragán–designed Galvez House, Mexico City, 1955. Collection of Emilia Guzzy de Galvez, Francisco Kochen photo

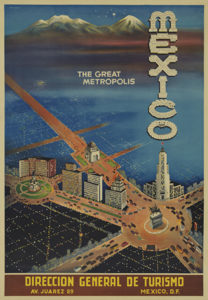

The exhibition traces this dialogue through four sections: Spanish Colonial Inspiration, Pre-Hispanic Revivals, Folk Art and Craft Traditions, and Modernism. This last focus may come as a surprise to many visitors, but the frenetic urbanization of both places in the mid-twentieth century provided perpetual fodder for trans-border exchange. This was particularly true of Los Angeles and Mexico City, which both developed into sprawling metropolises in the decades following World War II. Burgeoning populations required new housing and civic spaces, providing opportunities and challenges for architects and designers. While modernists in both places were profoundly influenced by functionalist, unornamented designs of the European avant-garde, they also looked to each other.

Mexican Bauhaus teapot by Peter Shire, 1980. Collection of Ava R. Shire, © Peter Shire, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

The conversation predated the postwar boom. In 1937, California architect, photographer, and author Esther Born published The New Architecture in Mexico, the first book on the subject in any language. Architect Ernest Born, her husband and collaborator, mused in the introduction that “[Mexican architects] are engaged in the same pursuit as ours. . . . The point of view is familiar but the accent is different. That same year one of Los Angeles’s most progressive architects, Austrian emigré Richard Neutra, received an invitation to speak in Mexico, where his many admirers sought his expertise on the integration of buildings in the landscape. He returned the compliment in his introduction to I. E. Myers’s 1952 book Mexico’s Modern Architecture/Arquitectura moderna mexicana, praising Mexican architects for “saying an open-eyed ‘yes’ to a new architectural expression of a new situation.”

Robert Berns Beach House, Malibu, designed by Gordon Drake, 1951, in a photograph by Julius Shulman, 1953. Chairs by Clara Porset and a tapestry by Saul Borisov are on the deck. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, photo © J. Paul Getty Trust

In the subsequent years, leading Mexican architecture journals Arquitectura/México and Espacios published several of Neutra’s projects, as well as those of other California practitioners. They expressed a particular affinity for the Case Study House program, which was initiated by the avant-garde Los Angeles journal Arts and Architecture to address postwar housing needs. Envisioned as prototypes for modern living, these modest houses combined the latest advances in modular construction with a genuine attention to comfort and leisure. Photographer Julius Shulman’s glamorous images of these homes, which helped to establish their iconic status in American architecture, also appeared in Mexican publications. Architects in modern Mexican developments, such as the garden suburb Jardines del Pedregal, employed many of the same elements—glass curtain walls, daring cantilevers, and fluid boundaries between indoor and outdoor spaces—while meeting their wealthy clients’ expectations for luxury, scale, and formality.

Peineta chair from the Continental American Collection by Edmond J. Spence, manufactured by Industria Mueblera, 1952. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Decorative Arts and Design Council Fund, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Esther McCoy used Shulman’s photographs in her quest to find a US distributor for the work of Clara Porset, one of Mexico’s leading designers. Porset advocated for a distinctly Mexican form of modernism that derived from the nation’s heritage of handcraft. In her own designs, she captured the essence of vernacular forms such as the butaca, stripping away traditional ornamentation to create airy, minimalist furnishings in modest materials. At the critic’s encouragement, Porset sent chair samples to Shulman, who incorporated them into several of his staged images of California homes. Though McCoy’s effort to find US distributers for Porset’s furniture was ultimately unsuccessful, it demonstrates the close ties between Mexican and Californian design.

Californians also looked to Mexican crafts for inspiration, expressing admiration for everything from the abstract patterning of woven serapes to the vibrant whimsy of ceramic figurines. Many designers and craftspeople made pilgrimages to the remote villages of Oaxaca and Jalisco, seeking respite from fast-paced city life as well as training from expert artisans. Others had more sustained engagements with these places and practices. Raul Coronel created distinctive stoneware by combining aspects of the folk ceramics that had surrounded him as a child in Mexico with the principles he had learned through his rigorous modernist training at the University of Southern California. Los Angeles designers Jerome and Evelyn Ackerman produced their mosaic and textile designs in traditional craft workshops in and around Mexico City, allowing them to achieve their ideals of both handmade quality and affordable prices.

A swimmer dives into the pool of Casa Marbrisa, Acapulco, designed by John Lautner, 1973, in a photograph taken by Julius Shulman the same year. © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

While Californians went to Mexican villages in search of pastoral authenticity, postwar Mexican leaders aspired to US-style urban and industrial development. Newly constructed resorts like Acapulco attracted movie stars and other elite tourists, who enjoyed the dramatic landscape as well as its elegant modern buildings. The visionary Los Angeles architect John Lautner built his only Mexican commission there, embedding the circular concrete Casa Marbrisa (1973) in the rocky coastal cliffs to open up a spectacular view of Acapulco Bay.

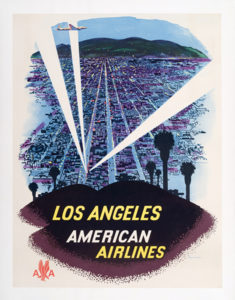

Los Angeles by Fred Ludekens for American Airlines, c. 1960. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of Martha and Bruce Karsh in honor of the museum’s 50th anniversary, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

This futuristic strain of California modernism encouraged designers in Mexico to create their own experimental projects in space-age forms and industrial materials. Po Shun Leong, a British designer working in Mexico, was inspired by the sculptural fiberglass furniture of San Diego designer Douglas Deeds that he saw in an exhibition catalogue from the Pasadena Art Museum’s influential California Design series. Leong used the material to create an innovative chaise, developing a simple sliding joint that allowed the user to transition between a seated and reclining position without getting up.

Mexico: The Great Metropolis, poster by A. Regaert for the Direccion General de Turismo, Mexico, c. 1950. LACMA, Decorative Arts and Design Council Acquisition Fund, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

In 1981, Leong moved to Southern California. He installed one of his chaise longues next to his backyard swimming pool, where it remained until he donated it to LACMA in 2015. In Found in Translation, it sits on a platform next to one of Deeds’s fiberglass prototype chairs, together for the first time. The exhibition is full of these moments, demonstrating again and again how the movement of people, ideas, objects, and images across the border has shaped both California and Mexico. While the last year the exhibition examines is 1985, the cross-cultural exchanges are ongoing, continuing to enrich both places.