Courtesy Victor Deupi and Lin Arroyo Collection

Courtesy Victor Deupi and Lin Arroyo Collection

Exhibition

Preview: Cuban Architects at Home and in Exile: The Modernist Generation

This article was originally published in Cuban Art News on October 25, 2016 and appears in Modern Magazine with their permission.

Early next month, the Coral Gables Museum turns the spotlight on modernist architecture by Cuban designers on the island and abroad. Victor Deupi co-curated the exhibition with Jean-François Lejeune, his colleague at the University of Miami School of Architecture. Here, Deupi gives us a pre-opening glimpse of Cuban Architects at Home and in Exile.

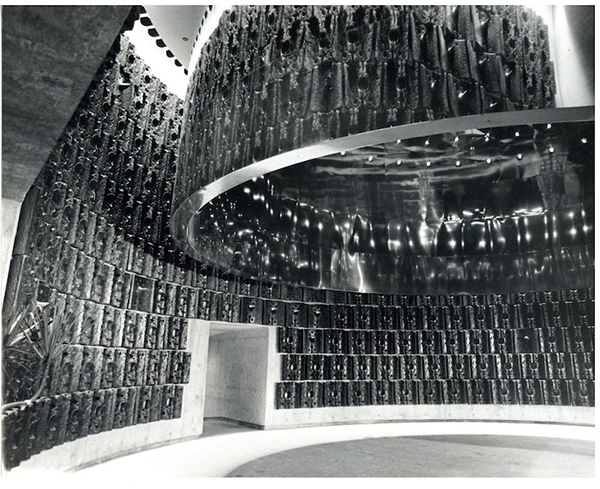

Emilio Fernández, building for the Liga Contra la Ceguera (Anti-Blindness League), Marianao, Havana, 1957–59

Courtesy Victor Deupi and Emilio Fernández Collection

How did the project come about?

As a Cuban-American I had always wanted to engage with Cuba, even though my early research was on Spain and Rome in the 18th century. My parents grew up in Cuba and studied architecture in Havana in the 1950s. Yet as a young scholar I was drawn to Europe.

Nevertheless, while doing some research at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York a few years ago, I came across a collection of un-catalogued drawings, watercolors and lithographs of the 20th-century Cuban-American artist Emilio Sánchez, who lived both in New York and Havana.

That discovery started this journey. When I arrived in Miami two years ago, the dean of the UM School of Architecture, Rodolphe el-Khoury, asked if I could extend my research on Cuban artists to include architects who worked both in Cuba and abroad. I reached out to my colleague Jean-Francois Lejeune, who had done some work on Cuba previously, and the project took off immediately.

Arquitectos Unidos at lunch in the Mulgoba Restaurant near Rancho Boyeros

Courtesy Victor Deupi and Humberto Alonso Collection

Why do you think it’s important to look at mid-century architecture by Cuban architects on an international scale? What can this perspective bring to our understanding of Cuban architecture and architects?

Havana has an architectural patrimony that pertains to everyone, and now more than ever, that patrimony is under great stress. The effects of age and the impact of global tourism will certainly test the limits of the city’s infrastructure.

But this project is not just about Cuba. The architects under consideration spread Cuban culture beyond the confines of the island to countries such as the US, Mexico, Puerto Rico, Venezuela, France, Spain and many more. To date, however, there is no study that examines the life and work of mid-20th-century Cuban architects in both Cuba and abroad.

It is the aim of this exhibition to bring together important works of art and architecture that extend beyond the island of Cuba and reveal the sense of Cuban architectural culture at home and away.

The project will focus on several Cuban architects and artists whose work represents the challenges that their generation had to face to establish themselves in a country on the verge of dramatic change, and then as expatriates in various foreign countries. The aim of the exhibition is to understand 20th-century Cuban architectural culture in its widest context.

Raúl Álvarez, Enrique Gutiérrez & Rolando López Dirube, The Timeless Cylinder, One Biscayne Tower, Miami, 1973

Courtesy Victor Deupi and Raúl Álvarez Collection

In your opinion, what do Cuban architects and architecture bring to our understanding of midcentury modernism?

Cuban mid-century architects largely practiced in a domestic studio format (casa/taller). There were very few large firms on the island and the architectural culture relied to a great extent on patronage (government or private). There was little speculation.

Consequently, Cuban architects were able to produce work of the highest standard while maintaining very little overhead. It was a kind of arts and crafts culture that they maintained even outside of Cuba. The relationship between master and apprentice was established at the universities where teachers and students often worked together on real projects. Many Cuban architects took up teaching positions after they left Cuba. Today more than ever, we have a great deal to learn from this architectural culture.

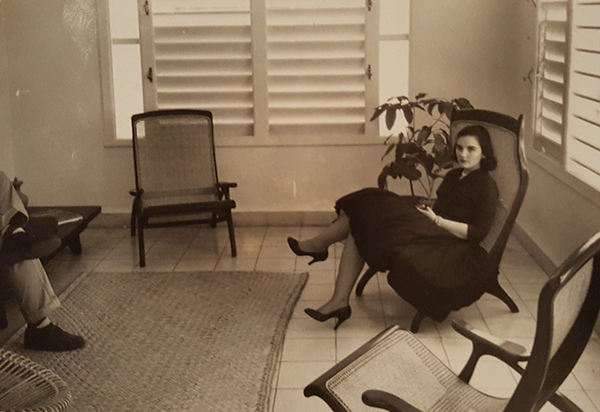

Margarita Cano with her collection of furniture by Ricardo Porro, Havana, c. 1956

Courtesy Victor Deupi and Margarita Cano Collection

What sort of materials are included in the show? photographs, models, documentation?

The exhibition brings to light both public and private collections. Institutions like the Cuban Heritage Collection at the University of Miami and the Bacardi Archives have contributed original documents, drawings, photographs, letters and other ephemera.

Similarly, private collections that have been largely stored in Cuban architects’ closets—or with their families—have yielded a great deal of material.

Additionally, we will provide videos dealing with Cuban architects’ private lives, examples of Cuban architecture throughout the island, and details about the events in 1959 that affected the profession and teaching of architecture in Cuba.

Architect Eugenio Batista in an undated photograph

Courtesy Victor Deupi and Cuban Heritage Collection, University of Miami

How is the exhibition structured?

It’s organized thematically around eight topics: Architectural Education & Practice; Art, Architecture & Design; La Casa Cubana, including both the historical house and the modern; Making the City, including the historic city, civic space & civic buildings, and commercial & residential; and Tourism and Leisure.

Nicolás Arroyo & Gabriela Menendez, Palacio de los Deportes, Ciudad Deportiva, 1955–57

Courtesy Victor Deupi and Lin Arroyo Collection

Who would you say are the “stars” of the show—the well-known architects whose work deserves a closer look in our time?

The Cuban Heritage Collection at the University of Miami already has the collections of Eugenio Batista and Nicolás Quintana. A great deal of material from these two important figures will be on display. In addition, the living architects Raúl Álvarez, Enrique Gutiérrez, Humberto Alonso, and Ermina Odoardo have contributed significantly. Finally, the families of Nicolás Arroyo and Gabriela Menéndez, Max Borges, Ricardo Porro, and Carlos Artaud, among others, have contributed very generously to the exhibition.

Take, for example, Nicolás Arroyo Márquez (Havana, 1917–Potomac MD, 2008) and Gabriela Menéndez García-Beltrán (Havana, 1917–Potomac MD, 2008). He received his architecture degree from the University of Havana in 1941, then married his classmate and fellow architect. Together they formed the hugely influential firm of Arroyo y Menendez Architects, practicing in Cuba until 1959.

Among their most notable projects in Cuba are the Ciudad Deportiva (1955–57), the Plan Piloto of Havana (1959, along with Mario Romañach, Josep Lluís Sert and Paul Lester Weiner), the Teatro Nacional (1954–60 with Raúl Álvarez), and the Havana Hilton (1958 with Welton Becket and Associates).

After the Revolution, Arroyo and Menéndez settled in Washington, DC, and established a practice that focused on residential, commercial, and resort architecture. Arroyo was a member of the American Institute of Architects and served on the US Commission of Fine Arts from 1971 to 1976.

Carlos Artaud, Vivienda Economica, Havana

Courtesy Victor Deupi and the Vidal Artaud Family Collection

And who else will be stepping into the spotlight?

Among the lesser-known architects whose work we are including, Emilio Fernández and Carlos Artaud stand out as two who deserve much greater attention. The vast body of work each produced is impressive. Artaud in particular was developing affordable housing (viviendas económicas) very early on.

While Fernandez and Artaud left Cuba, Ricardo Porro (Camagüey, 1925–Paris, 2014) returned to Havana after the Revolution and participated in the design of the National Art Schools along with Italian architects Vittorio Garatti and Roberto Gottardi.

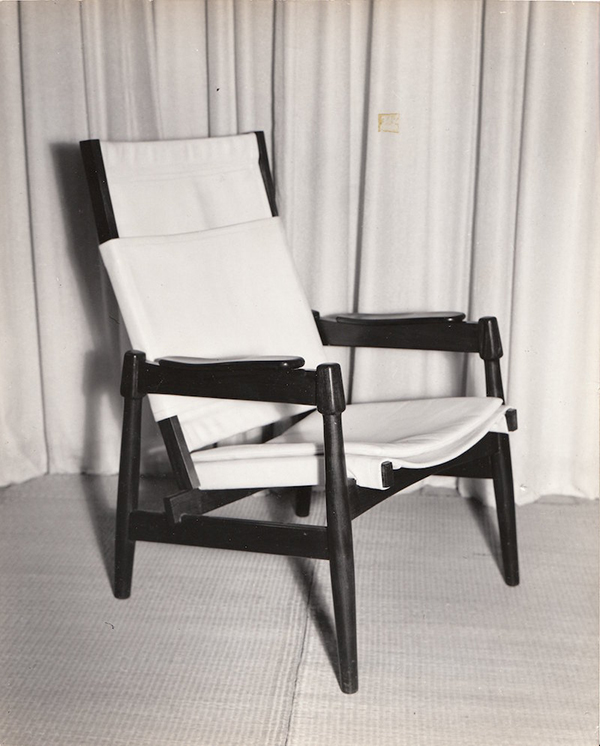

A chair designed by Myrtha Merlo Vega

Courtesy Victor Deupi and Myrtha Merlo Vega Collection

In a previous conversation, you mentioned that women architects in particular will be included.

Several women architects emerged in this period. Both Gabriela Menéndez and Rosa Navia were married to architects (Nicolás Arroyo and Jose Gelabert respectively), yet their work stands on its own. Both ran the offices when their husbands took government positions in the Ministry of Public Works and the City of Havana, and both produced important designs.

Gabriela Menéndez designed the Presidential Palace as part of the Plan Piloto for Havana (1959) and Rosa Navia designed the Ministry of Transport (1961). Ermina Odoardo started the practice that she and her husband ran in Cuba (Ermina Odoardo–Ricardo Eguilior, Arquitectos). She was the main designer while he was more of the technician. And Myrtha Vega was a leading designer of interiors and furniture.

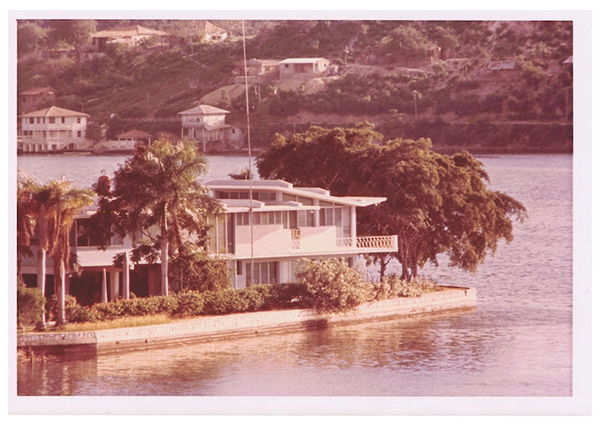

Ermina Odoardo & Ricardo Eguilior, House for Joaquin and Caridad Bacardí, Santiago de Cuba, 1955–56

Courtesy Victor Deupi and Ermina Odoardo Collection

Anything you’d like to add?

The project is dedicated to my parents, their generation, and their teachers and colleagues who gave us, through their dedication and passion, the Modern architecture of Cuba. It is a work of tremendous love and gratitude.

Cuban Architects at Home and in Exile: The Modernist Generation opens Friday, November 4, at the Coral Gables Museum, where it runs through February 26.

________________________________________________

Susan Delson has been the New York editor of Cuban Art News since 2009. A former member of the Metropolitan Museum of Art education department, as editor she has worked with the Museum of Modern Art, Asia Society, El Museo del Barrio, and other institutions. Her books include the film study/biography Dudley Murphy, Hollywood Wild Card and (as editor) Ai Weiwei: Circle of Animals. As a magazine editor, she has worked at Forbes, Louise Blouin Media, and other companies.