Photography by Cervin Robinson

Photography by Cervin Robinson

Architecture

Paradise Lost

IN THE 1960S, WHEN BRIDGEHAMPTON WAS A TAPESTRY of potato farms, dunes, sky, and sea, my grandparents purchased a small house on the beach. Their simple shingled wood-and-glass home was by no architect of note, but it kept good company. As farmland turned into residential enclaves, and the fields were replaced by crisp landscaped lawns, a new type of architecture emerged, one that was bravely contemporary in look and feel, but still communing with the landscape. During the summers I spent there with my family, my frequent bike rides in and around town would take me breezing past houses designed by the likes of Charles Gwathmey, Philip Johnson, Andrew Geller, and most notably, Norman Jaffe—an informal yet formidable education in modernism that cultivated a deep affection for the local architecture.

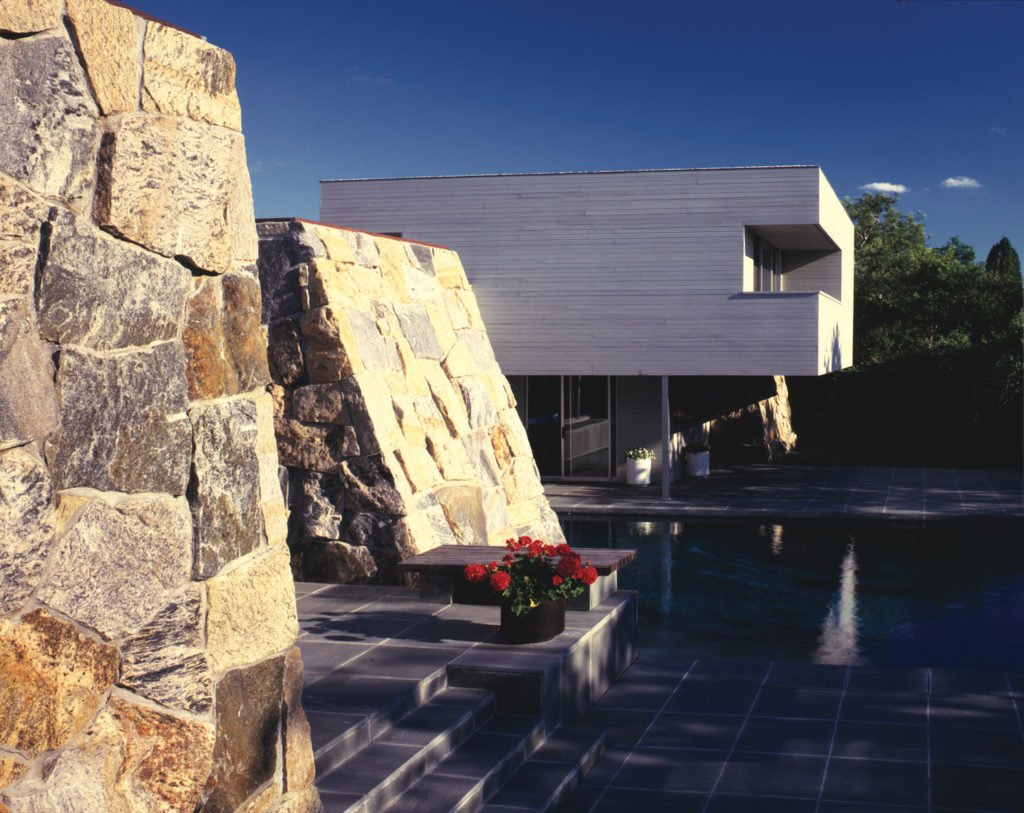

Architecture and landscape design came together as a unified concept in Norman Jaffe’s Lloyds House, 1977, in East Hampton, New York. Here, the pool seamlessly met the exterior of the house, encircled by the rear bedroom wing and stone wall. The house was recently razed. Photography by Cervin Robinson

Down the road from us was Sam’s Creek, an orderly cul-de-sac in which were six houses designed by Jaffe over the course of about a decade, from the early 1970s through the ’80s. These homes—aligned on adjacent plots and nestled into the land—exuded a graceful restraint with their low-lying linear forms. In a letter to Paul Goldberger, who was then the architecture critic at the New York Times, Jaffe wrote, “At Sam’s Creek I learned in most cases it is the garden, the land forms and the lighted interior spaces that are the issues in residential design. Community and privacy. Nature and family.” This deference to the region’s natural landscape and its local architectural language played a strong role in Jaffe’s work from the moment he arrived in the Hamptons to design a house for Sascha Burland in 1967. He explored the delicate relationship between nature and dwelling, between interior and exterior space, keeping a gentle footprint on the land. “Arriving for the first time I was taken with the at, green pool table horizontal character of the landscape, the sky came down dramatically. . . . The shapes on the horizon were only agricultural buildings or natural groves of vegetation,” he wrote in the letter to Goldberger. “In the sixties the character of the farms dominated.”

Norman and Miles Jaffe, about 1965. Courtesy Miles Jaffe

Jaffe wove the farmhouse vernacular and local material palette—stone, wood, and shingles—into modern compositions that favored canted roofs, angular massing, and the dynamic play between light and space in his interiors. The landscaping always figured prominently in his designs; he implemented berms and plantings to work harmoniously with his architectural forms, perhaps reflecting the profound influence of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Prairie style, which he greatly admired. This balance between the land and built environment reveals itself in the twenty-five plus houses he designed in the course of his first decade in the Hamptons, the majority located in Bridgehampton, which Jaffe, too, called home. Burland, Jaffe’s first client there, recalled his approach in the September 1980 issue of Hamptons Magazine: “He thinks of shapes. He’s more of a sculpture architect, rather than one who designs spaces only for a certain type of living.”

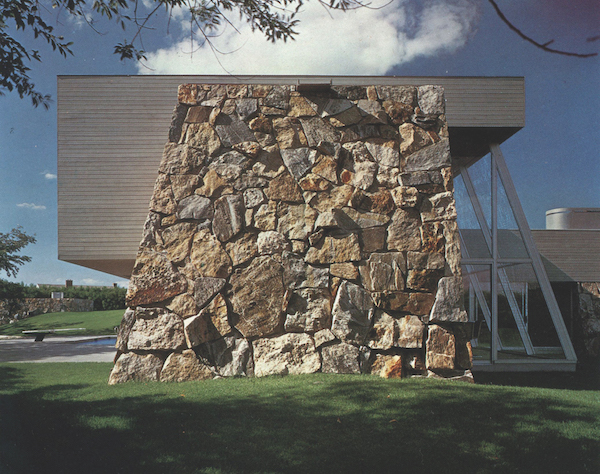

The muscular wall on the southeast corner was made of Westchester granite, a stone that appeared throughout the Lloyds House. Jaffe saw this project as a turning point in his ability to design with large masses of stone, as he expressed in a letter to Paul Goldberger. Photography by Cervin Robinson

Jaffe hit his stride in the design of the Lloyds House in East Hampton in 1977. Down the street from the beach, the four-bedroom home was to be situated on a snug, roughly one-acre plot, which, as Alastair Gordon explained in his monograph, Romantic Modernist: The Life and Work of Norman Jaffe, Architect, proved to be more challenging than sites that boasted ocean views or spacious properties. Though these initial restrictive circumstances forced Jaffe to reach into his wellspring of ideas and think creatively, the result was a lively arrangement of cantilevered, rectangular volumes, anchored by large stone walls. On the southeast side, floor-to-ceiling glass enclosed the dining room, bringing in ample light and offsetting the brawniness of the stonework. What the site might have lacked in vista or seascape, it made up for in elegant landscaping and detailed planning. A swimming pool was carved into the structure—its shape dictated by the irregular contours of the house and the water seemingly engulfing the massive stone wall.

A floating staircase led to the living room and dining area. Photography by Cervin Robinson

According to Jaffe’s son Miles, the house was a personal favorite of his father’s. In the Goldberger letter, he acknowledges the project as a landmark in his career: “My ability to handle the detail for larger masses of stone improved. Masses becoming bolder, the plan simpler and clearer. I had learned something about building and my sketches came closer to what the finished product became.”

Miles, who is also an architect, thinks the house was one of his father’s nest. “The visual appearance, the balance of forms, the simple materials were very strong,” he says. “And it functioned well, which was beautiful. Sometimes his houses were lacking in function, but it all came together in the Lloyds House.”

The solidity of the stone replace in the living area formed a counterpoint to the light from the sliding glass doors and skylight. Photography by Cervin Robinson

The house was recently razed, and in its place now is a seven-bedroom home that is a mash-up of historic American architectural styles (more commonly referred to as a McMansion). The tide of development hasn’t abated in the last forty years, and tastes have changed. The humble, and often idiosyncratic, homes built in the 1960s and ’70s are frequently supplanted by larger structures designed in a more traditional vein, striving for a new kind of grandeur.

The floor-to-ceiling glass panes created an open, light-filled dining space with views of the rolling lawn. Photography by Cervin Robinson

By the time of his unexpected death in 1993, Jaffe had witnessed the onset of development and was deeply conflicted about the changes to his beloved landscape, and his role in the ecosystem of Hamptons real estate. “We can apply our craft, art and inspiration hopefully to serve jointly architecture and our clients,” he wrote in the Goldberger letter. “The subtleties of understatement are generally not part of their [the clients’] daily lives. This power motive is often not comfortable to a gentle dialogue with the natural surroundings.” Having grown tired of the monotony of residential projects coming his way, Jaffe branched out and went on to design several celebrated buildings, including the Gates of the Grove synagogue in East Hampton and the commercial high-rise 565 Fifth Avenue in midtown Manhattan.

We sold my grandparents’ house ten years ago. And it too met the fate of the Lloyds House, along with so many others in the Hamptons. When I’ve gone back to Bridgehampton and biked around those same sandy roads, I notice fewer of those geometric forms peaking out from behind the hedges— fewer expressions of those modernist ideals that Jaffe and his peers brought to life through their architecture.

The house illustrated Jaffe’s mastery of shape and texture, with its bold rectangular forms and material palette of glass and stone. Photography by Cervin Robinson

LIKE FATHER, LIKE SON

Recently, Miles Jaffe completed a renovation and addition to a prototype of a weekend home Norman originally designed in 1975, known as Swan Creek House. We spoke with Miles about this unique opportunity to update and build upon his father’s initial vision and design concept.

Modern Magazine: Could you tell me about the original commission? What do you think was Norman’s intent and plan?

Miles Jaffe: The original house was not intended as a full-time residence. Norman designed it as a prototype for a simple weekend getaway: two and a half bedrooms, two baths, with only two materials—wood and glass. The intent was to create a modern vacation house at a modest price point. This was in part a reaction to the rapidly growing demands of ever-wealthier clients.

MM: When you were tapped to take on the renovation and addition, what was your thought process and approach in both restoring and expanding the house?

MJ: The renovation transformed the existing 1,800-square-foot building into a one-bedroom house with living spaces sized to support a three-bedroom addition. Functions were updated to contemporary standards and the interior was completely refinished. I imagined the house as if my father were tuning it up, adding stone— the missing signature Jaffe element—and the fine detailing necessary for a full-custom project. Further enhancements included re-creating a few of Norman’s early furniture designs and the addition of a copper roof with a solar energy system.

MM: What were some of the challenges of the project, and how did you resolve them?

MJ: The most difficult design problem was how to add on. The challenge was not to upstage my father’s work but rather to enhance it. What would Norman do? Eventually I found the solution—a reflection of the same form positioned to complement the original. Within this envelope I riffed on the established themes to create a family wing that fulfilled the program requirements.

Having responsibility for both interior design and landscaping allowed me to do what Norman had only been able to achieve on a few select projects—create a comprehensive, harmonious design unmolested by competing professionals. This is the sweet spot in architecture. Even better, this project was a chance to work with my father again. It’s been a labor of love.

Miles Jaffe’s renovation and addition to this 1975 weekend house pays homage to his father’s design sensibility and legacy, with subtle but critical changes, including refinishing the interior, adding stone elements, and implementing a solar energy system. Miles Jaffe Photo