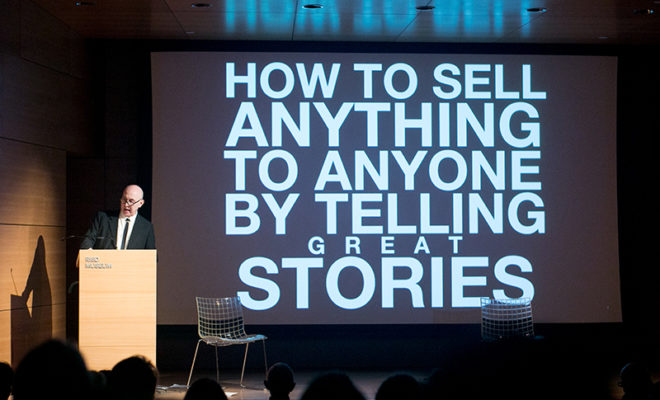

Murray Moss's presentation at RISD. Photograph by Jo Sittenfeld.

Murray Moss's presentation at RISD. Photograph by Jo Sittenfeld.

Design

Murray Moss: A Class Act Comes to RISD

Contrary to what might be expected of a design-world celebrity, Murray Moss is refreshingly unpretentious and eager to share his considerable knowledge with anyone showing the least bit of interest in his favorite subject. Hence, the latest project for this design guru, whose eponymous SoHo emporium introduced a generation of collectors to iconic objects like those now found in museum collections, and stores, across the country. Since closing the business in 2012, Moss and partner Franklin Getchell have been in demand as consultants to a variety of clients, including several museum shops. But his recent affiliation with the Rhode Island School of Design is especially close to his generous heart: as a faculty member, he has the opportunity to teach the next generation how to understand design. How is he doing it? With a characteristically innovative approach: a graduate-level course he calls “Torpedo Lab,” a case study/think tank for which the classroom is his own object-filled home.

Moss’s 1929 garrison-style house in Hamden, Connecticut. Photograph courtesy of Moss Bureau.

Moss and Getchell, partners in life and business for forty-seven years, moved last year from a sleekly modern New York apartment to a 1929 garrison-style house in Hamden, Connecticut, which he describes as “a pastiche: some early American, some Rococo, with elements of a Noel Coward set,” and not at all what they were looking for. “We wanted a small modernist house in convenient commuting distance to New York. After two years of looking, the real estate agent brought us to see this house. I took one look and said, ‘Let’s buy it.’

Interior view of Moss’s home featuring a Gaetano Pesce light.Photograph courtesy of Moss Bureau.

This wasn’t his first impulsive life-change. Chicago-born Moss didn’t plan to be involved in design, and never aspired to open a store. He began his professional life as an actor, and switched careers to run the high-end Ronaldus Shamask fashion business. During trips abroad, he became enamored with the beautiful modern objects he saw in Italy—objects not then available in the United States—and decided to bring them to America. He and Getchell opened the Greene Street shop in 1994, when SoHo was a burgeoning art gallery neighborhood. Showcasing merchandise in glass cases like museum exhibits, Moss became a magnet for design junkies, and introduced an impressive roster of international design celebrities to collectors, curators, and designers.

The now closed Moss store in New York City. Photograph courtesy of Moss Bureau.

The RISD students in Moss’s seminar, too young to remember the store, will be exposed to the Moss approach to in five biweekly sessions this semester. He is using the objects in his highly personal collection as tools to look at, touch, and discuss, helping the students to see connections and draw parallels between disparate works of different styles and periods. “Not exactly a petting zoo,” he says, “but things that have meaning to me that I think are interesting for them to look at and put in hand.” He admits to some concern: “It’s a huge responsibility—it’s a different thing when you have to articulate what it is you do and how you approach something.” Though he believes it will benefit the students to leave campus with a different kind of experience. The course is limited to graduate students: “I wanted students about to begin a professional career. It’s a big change—from someone expected to ask questions to someone expected to answer them. I want to help them think of answers.”

An interior view of Moss’s now closed storefront in New York City. Photograph courtesy of Moss Bureau.

RISD also sponsored two well-attended public lectures by Moss last fall, in which he discussed his experiences with innovative design, and his then-transgressive approach to display and merchandising. About her recruiting of Moss, President Rosanne Somerson says, “At RISD, where immersive making is fundamental to critical and integrative thinking, the customized set of experiences that Murray has designed will foster dialogue around object narratives and interdisciplinary design…and inspire the next generation of creative leaders.”