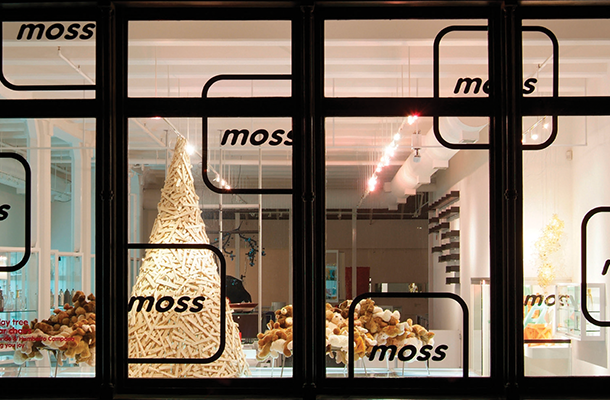

A view through the Moss storefront window on Greene Street in SoHo, New York. This holiday display featured the Campana Brothers’ Favela Tree and Teddy Bear chairs.

A view through the Moss storefront window on Greene Street in SoHo, New York. This holiday display featured the Campana Brothers’ Favela Tree and Teddy Bear chairs.

Design

All Sales Final

Please Do Not Touch (and other things you could not do at the design store that changed design) By Murray Moss and Franklin Getchell (Rizzoli, $55)

MOSS, THE BOOK, IS A LOT LIKE MOSS, the store, which is to say entertaining, titillating, genre-bending, and subversive—beginning with the cheeky title, Please Do Not Touch (and other things you could not do at the design store that changed design). For those who never had a chance to visit the dearly departed SoHo emporium during its eighteen-year run (1994–2012), or one of its two shorter-lived Los Angeles satellites, it’s true that manhandling the merch was verboten—nay, impossible, unless you asked a monochromatically attired salesperson to unlock one of the museumlike glass-and-steel vitrines in which visionary proprietor Murray Moss obsessively arranged arch tableaux of avant-garde fruit bowls, Meissen polychrome porcelain, postwar Italian vessels, Dieter Rams calculators, Lobmeyr stemware, Gaetano Pesce meltingish resin tables, Studio Job marquetry, and other high-concept bibelots in a manner that uncovered their common logic. No: you couldn’t touch. But you could look and you could covet and, most important, you could think…and thus rethink everything you understood to be true about modern design. Moss was in the business of blowing minds, shifting paradigms, dismantling boundaries, and building a market and audience for capital-D design.

This did not always translate to runaway sales, as it turned out.

At Moss, goods were presented as if they were rarities in a museum: placed in vitrines and on raised platforms labeled with the admonition “Please do not touch.”

Please Do Not Touch is ostensibly a memoir documenting the store’s rise from an 1,800-square-foot Greene Street storefront to its early aughts apex as Establishment Institution to its eventual denouement, told from the alternating viewpoints of Moss and his partner in life and business, Franklin Getchell—a fun conceit that neatly mirrors their interdependent but parallel roles as creative innovator and “enabler/facilitator.” Rather than write in tandem, they penned their manuscripts separately, and didn’t read each other’s take on things until the galley stage, which led to some humorous he-said, he-said moments. The narrative structure is a sort of Eisensteinian montage, interweaving the authors’ ruminations on topics like holiday gift wrapping and their killer Tupperware party with assorted source materials: reproductions of the employee handbook, articles Moss penned for Pin-Up and Interior Design, a master’s thesis excerpt, exhibition catalogue texts, wall signage. Also interspersed are visual essays—product still lifes by longtime collaborator Chalkie Davies—and less-slick snapshots of the various store interiors over the years.

Offered at Moss: the Flower Ball by Takashi Murakami for Molten, 2002.

Moss, the person, likens Moss, the store, to a form of theater, one in which the scenography was both setting and protagonist. It is thus satisfying and riveting to hear all the behind-the-curtains craziness the production entailed. The gentlemen dish on the mechanics of bridal registries, the complex geopolitics of global design fairs, the emotional tenor of the designer-retailer relationship, the devastating financial impact of the 2008 recession, and the death-defying logistics of such an ambitious exhibition program. Also: how much elbow grease, miles of Bounty paper towels, and truckloads of white paint were necessary to uphold the pristine aesthetic.

The store’s do-not-touch shtick was a canny psychological device to instill must-have-that! desire and spur sales, but it could feel overly museumlike, which occasionally undermined the mission of the whole enterprise: to make high design accessible. The authors avoid falling into that trap here. This is Murray—and Franklin—unfiltered and unmediated, as they divulge the thinking, questioning, agonizing, and philosophizing behind their decision making. You feel right there with them as they navigate the period before design became a full-blown cultural force—and before e-commerce disrupted traditional retail. It’s insightful, it’s funny, it’s devastating, it’s…well…touching.