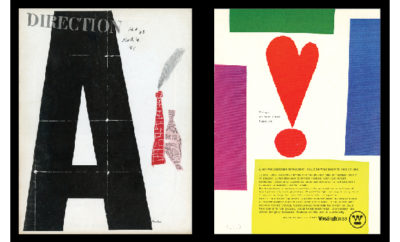

Feature

Modern Japanese Tea Bowls

This Sekisoh (accumulated layers) tea bowl by Izumita Yukiya, displays his technique of creating layers by painting clay onto paper.

A HUNDRED YEARS AGO, when Marcel Proust famously wrote about a cup of tea, he was introducing a modern idea, the phenomenon of involuntary memory that can recapture the essence of the past because of the masterful design of recollection. If you read carefully you’ll see that his fictional teacup hardly had a material essence. What did it look like? Did it resemble the well-designed teacups in still lifes rendered by Henri Fantin-Latour, whom he writes about in The Guermantes Way? More likely, if Proust was imagining a teacup from his past, it was less tasteful, wide brimmed, stretched low, painted with prim flowers like the plates on the wall in his aunt’s house in Illiers-Combray. Never described as an object, Proust’s teacup served his purposes only as a container for the perfume of warm tea and cake crumbs, the accidental and fragrant concoction that surprisingly called up lost memories. If it existed as a repository for an obliterated and long-forgotten past, the cup was also a holder of ideas of French Japonisme, experienced primarily through taste and smell, imagination and consciousness, rather than through the eyes.

“…the whole of Combray and of its surroundings, taking their proper shapes and growing solid, sprang into being, town and gardens alike, from my cup of tea” — Marcel Proust

Tsujimura Shiro’s Big Ocean tea bowl is in the Oribe style, which is known for its shining black color (achieved with a dark green copper glaze), and a coating of white slip enlivened with drips and flows, and the radiant yellow of kintsugi, a material often used for repair work.

I thought about Proust’s teacup recently when I was visiting the Ippodo Gallery in New York, where there was an exhibition of contemporary Japanese chawan, modern tea bowls constructed in the traditional Japanese forms and associated with the ritualized tea ceremony. The tea bowl and tea utensils continue to be central to the Japanese pottery tradition, even to contemporary potters oriented within the avant-garde, who work to create a perfect tea bowl within their lifetime. Like Proust’s teacup, these bowls are holders of memory, or rather, historicized memory encoded by those who know the tea ceremony. And, like his teacup, they are meant to be experienced by all the senses: by the eye, which perceives them from every direction; by the hands, which pick them up, touch their clay walls, bear their weight, feel the heat con- ducted through their skin; even by the lips touched to the irregular surfaces of the rim. Within the tea ceremony, they also have a conceptual purpose, linking host to guest and human imagination to nature and spirituality.

There was a great variety among the bowls in the Ippodo exhibition, representing all the styles employed today: Raku, Ido Hagi, Karatsu, Oribe, and Shino. Some were in- tended for use and others were clearly non-functional. Some shimmered with metallic slip and others were rugged, scratched, or “clog-shaped.” As objects, they had atotemic quality, standing together like Cycladic figures, and I felt the temptation to think of them sculpturally. Like snuffboxes, antique pipes, or bells (and some of the bowls turned upside down would resemble monastery bells in shape and size), they can be appreciated for their beauty as art or craft, but within Japanese culture their value is more than the sum of their parts.

Tsujimura’s shallow tea bowl in the Oribe style. Here the decoration falls over the rim and into the bowl’s interior.

Among the sixteen artists represented in the show, two are outstanding representatives of the different directions taken by contemporary Japanese potters. Tsujimura Shiro is a master of traditional Japanese forms, and his tea bowls are owned today by major institutions including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, Harvard, Yale, and Princeton. The story of his life resembles a Japanese fairy tale: born in 1947, in the poverty of the postwar period, he moved as a teenager from the Nara Prefecture to Tokyo with the intention of becoming a painter. After seeing a famous Ido bowl he decided to dedicate his life to pottery. Tsujimura never trained with a master but started his career making one bowl at a time, which his young wife would sell on the street. A Buddhist monk known as a connoisseur of pottery bought one of Tsujimura’s bowls, and with that stroke of luck he began to build a reputation and moved back to Mima-cho, Nara, where he built his own house and several kilns. He lives there today, working in the wooded area by the mountain-side and continues to make up to five hundred pots in a morning, then selects two or three to be salvaged, fired, and glazed in the afternoon. After his pots are completed he sets them outside, along the path to his garden or in the woods so they will absorb the elements and achieve the weathered appearance, marks, and stains so highly prized in the famous bowls that have preceded his. Photographs of Tsujimura’s home show his pots covering the hills and grounds and trenches, strewn randomly and everywhere in heaps and stacks as if they were part of nature.

Tsujimura’s katsuwa (warped or clog-shaped) tea bowl gleams with a black enamel-like finish. The technique of Hikidashiguro, in which the iron-glazed pot was high-fired, then removed from the kiln and plunged into water, created subtle variations and shades of black to wash across the bowl’s skin.

Tsujimura’s bowls display profound technical mastery as well as the vitality and depth of character demonstrated by the great innovators of the tradition. He works in many of the classical styles and does not care about the region that his clay comes from. “I have never cared about a few scratches or marks on my pots if I could achieve the effects I want,” he has said. “My interest is in the less than perfect shape, in the less than perfect kiln.” You see this in the nicked matte of a black tea bowl with tiny dents in the rim or in the surface of the foot untouched by glaze. An Ido-style bowl is crackled all over in intricate spiderweb patterns and the remains of white slip cling in droplets surrounding the foot and base. I’ve been told that the test for a master’s bowl is that the weight matches how it feels—you never say, “Oh, it’s heavier than I thought.” When I pick up this bowl, it’s something like the weight of half a honeydew but fits absolutely naturally in my hands. Perhaps Tsujimura’s most beautiful series was done in 1993, a particularly inventive period when he lived in Devon, England, and created his Oribe-style Big Ocean bowl using a rich, lathered black glaze, white slip, and kintsugi, the gold repair material made from gold powder and lacquer. Rising to the challenge of capturing the wild sea on the surface of a pot, he splashed the surface in broad calligraphic strokes and puddles like an action painter.

Izumita Yukiya (b. 1966) represents a younger generation and demonstrates a virtuosity that mixes a deep knowledge of the traditional with many contemporary trends in earth art and sculpture. As a young potter, Izumita became fascinated with the many uses of pa- per—for writing letters, bearing sacred texts, or making paintings, wrapping, padding, preserving, shredding, even representing money—and he began to find ways to combine it with the clay he was working with. He developed a technique that uses paper as an armature that allows him to make fine ceramic strips, or accumulated layers, Sekisoh, that he can shape into waves and rolls and angles, sometimes reminiscent of origami. In his boxes, vases, and tea bowls he achieves something like the appearance of the folds of a fan or a series of waves or even reptilian zigzags. His style is both rugged and fragile, hard and soft; the surfaces sometimes achieve the abrasive texture of Giacometti’s bronzes.

The rough and pitted, razor-thin surface of Izumita’s Trench seems to pull the abstracted shape of a vase into a ceramic vortex.

Izumita’s Sekisoh tea bowl at the Ippodo Gallery was built from a clay mixed with grog to achieve an earthy, gritty, coarse texture, but the interior is finished with a contrasting copper-metallic glaze. Cutting away a portion of the clay wall, he transferred the piece to strips of paper that could be stretched and bent before being patched back in like the drooping folds of an old gown or withered skin. In a way the bowl looks like an ancient object, a relic, or the remains of petrified wood. The surfaces of Izumita’s objects sometimes have the organic quality of bark and sometimes the quality of marked and roughed concrete. The openings of his vases and boxes, pitted or rutted, once again reflect the classic Japanese aesthetic, valuing the markings of imperfection. More recently, his work, still virtuosic, has incorporated sculptural, abstract, and even heroic values. You can see this in the surfaces of the folded clay band titled Trench, as he breaks away from the functionality of a vase and dynamically folds and twists his shape into a ceramic vortex, all the while adhering to the principles of balance and sensuality intrinsic to the values he mastered in the tea bowl.

Izumita’s bold Sekisoh flower vase is built of accumulated layers of clay that has been shaped on paper.

Both Tsujimura and Izumita have made alterations while working in a tradition that has crossed centuries and geographic boundaries before plunging into our time. Proust saw his teacup as a memory vessel that could contain the debris of the past. The bruised and fractured surfaces of twenty-first-century tea bowls powerfully incorporate a modern sense of the erosion of time and the challenges of holding together nature and human history as they are constantly decomposing and being reconstituted within the small universes of these modest objects.

All photos courtesy of Ippodo Gallery, New York.