This quiet family vacation villa, completed by Studio Rick Joy in 2014, is secluded in the arid highlands of Sun Valley, Idaho. The living room features a fireplace of locally sourced small-rubble stone and a view of Baldy Mountain. EXCEPT AS NOTED, ALL IMAGES ARE JOE FLETCHER PHOTOS.

This quiet family vacation villa, completed by Studio Rick Joy in 2014, is secluded in the arid highlands of Sun Valley, Idaho. The living room features a fireplace of locally sourced small-rubble stone and a view of Baldy Mountain. EXCEPT AS NOTED, ALL IMAGES ARE JOE FLETCHER PHOTOS.

Architecture

Lessons from the Land

IT HAS BEEN FIFTEEN YEARS SINCE we made our first monograph, Rick Joy: Desert Works, with a moody close-up photograph of “my first house,” the rammed-earth Catalina House, on the cover. With that book, we aimed to define our process, collecting into printed form our thoughts on working in a desert context, our use of then-unusual materials, like exposed rammed earth, and our at-once straightforward and deeply emotional approach to the practice of architecture. Now twenty-five years after forming Rick Joy Architects, I seek to understand place anew.

The partially covered northern terrace also has a fireplace; a stair leads to a hidden roof terrace that offers a 360-degree view that can be enjoyed from chaise lounges, as well as the opportunity to sleep under the stars.

We have kept our desert home, but beyond that, so much has changed. While my firm began as “local” (to a hundred-mile radius of our studio), it has, over time, extended to sites far away from our strip of land in Tucson, Arizona, to the rolling hills of Vermont, the jungles of Mexico, the campus context of Princeton University, the urbanity of Mexico City, and the island cultures of Turks and Caicos, Ibiza, and Long Island. Yet we have remained dedicated to the same clarity we cultivated so many years ago.

A view of the Sun Valley house from the rear, surveying Baldy Mountain.

Our studio is in Tucson, deep in the Sonoran Desert, a wide-ranging landscape that begins in Baja, California, winds its way through northern Mexico and continues north of here. Our compound of seven earthen buildings is in Barrio Viejo on one of the oldest streets in the United States. A wooden door opens into our entry courtyard that is flooded with sunlight; our main work space, a long narrow studio with a glass wall that provides a thin barrier between inside and outside, demarcates this courtyard’s edges. A conference room, model shop, and more studio spaces reside in the other buildings that are linked by a series of exterior courtyards and pathways.

Comprising three cubes, the Desert Nomad house, 2006, sits in a remote, bowl-like land formation in Arizona and is in equilibrium with the famed Sonoran saguaro cacti. The living room, bedroom, and den each occupy one of the independent structures, requiring travel on footpaths to move between them. JEFF GOLDBERG/ESTO PHOTO

The studio campus is one of our earliest works—originally built as artist live-work spaces. Working in and around these structures deeply influences our process, as we absorb lessons from the architecture and the surrounding environment. The skylight at the end of the main office, the leafy shadows that speckle the white walls outside the studios, the deep shade from the buildings on the paths between, the crunching of the gravel underfoot, the difference between winter and summer light, the times when summer sunsets enter the studio at an angle that requires a couple of us to wear sunglasses at our desks, the months when we work with the doors open and feel the air flow through the studio—these are all experiences that influence the way we create.

Amangiri, 2008, a thirty-four-room luxury hotel and spa in southern Utah, is situated against a low Entrada Sandstone formation that allows guests to experience the natural beauty of the surrounding mesas and light shows.

My early buildings conveyed their character through massive earthen walls, through the way structure captures the movement of the day from light to dark and back again to light, through spatial feeling and the deeply felt moments of recognition that come with sensing the “thickened atmosphere”—as Steven Holl described it—of our architecture.

A building becomes architecture when graciously enlivened. It is the stage for personal events where daily life and momentary dramas unfold. Spaces condition behaviors as much as they are eventually conditioned by their inhabitants.

The architecture of the spa mirrors the erosion and silent passage of time that typify the surrounding rock formations.

This view of architecture is deeply humane and unfashionably grounded in patience and perseverance in observing habits, listening to nuances, sensing moods, and reading a place. Unique and intimate experiences involving place, nature, and especially light and darkness perpetually surround us. Whether it’s the swirl of yellow flowers beneath the paloverde tree in front of my house, the dark reflections of human shapes on the polished concrete floor at a recent gallery opening in Venice, the smoky coastal morning fog from my youth in Maine, or the few minutes when our immediate atmosphere becomes a deep blue at dusk, there is transcendent power in living in observance of nuance. This nearly constant interaction of seeing and recording has an enormous influence on the work.

One can gain a sense of place only by taking the time to become intimately immersed in its particular natural characteristics—the characteristics that make it unique at a broad range of scales.

Wet-treatment areas are defined by sculpted organic forms and natural or filtered light, while dry-treatment areas are lined with wood and illuminated with colored light. AMAN RESORTS PHOTO.

As architects, what are the means to enable this process of taking charge of a place’s locality without overstating our influence? We do this by working within the interstices and harnessing details: designing an ascent through an immersive stone maze when entering the Woodstock Vermont Farm, or by creating a long driveway to the Amangiri resort in the Utah desert to heighten the sense of discovery. Through constant exploration, we seek the balance between sensually attuned and sovereign inhabitation.

Sited in relation to remnants of historic fieldstone walls, a pond, and the road, Woodstock Vermont Farm, 2008, evokes the simple gable forms of vernacular New England architecture. UNDINE PRÖHL PHOTO.

Lately, my studio has been entrusted to expand the notion of place and home to the public realm. Public space deserves the same care in terms of these up-close and personal considerations of attuning as a house—sensitivity to the qualities of grace and calm, experiences that are personable and insinuate connectedness to a place and a community. For example, our design for the new transit hall and market for Princeton University delicately balances both the university’s and the township’s confidence and pride.

Distinctive to this architectural approach is the emergence of a unique identity of place, without falsifying history—in other words, searching for identity without being identical. We create these unique identities through direct sensory experience and conceptual insight while borrowing from and enhancing the emotional identity inherent to a context.

Designed as a retreat in New York City, 2012, this open, 1,000-square-foot loft is divided into distinct areas: cooking, sleeping, eating, and gathering.

The places we have been and that remain with us in our memory and imagination commune with the context, culture, and nature of new sites. This connection does not mean that the building and its inhabitants will simply inhabit a place. Rather, it inhabits them, stokes their awareness and soul. It creates lasting sensational depth to live by, getting beyond the surface and into the spirit where place and experience can identify with each other and coexist for a little while.

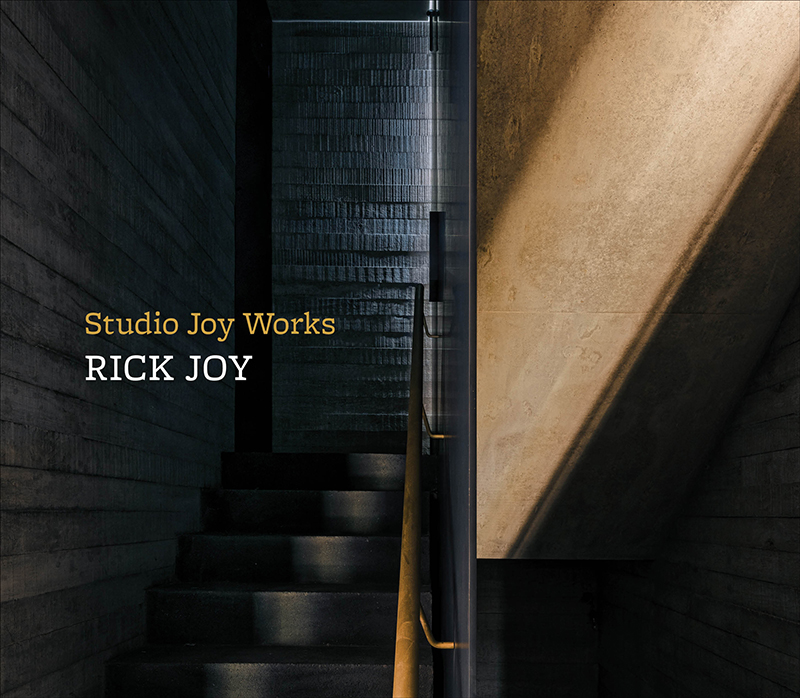

Studio Joy Works by Rick Joy, 2018. (Princeton Architectural Press, $55).

As I turn sixty later this year, I am taking stock of that milestone and realizing the merits of slowly becoming an elder and more of a mentor myself. Having some of the most switched-on young talents on the planet coexist and cocreate with me for more than a little while is the most meaningful aspect of my career in architecture.