Design

Claire Falkenstein: Small Sculpture/ Large Jewelry

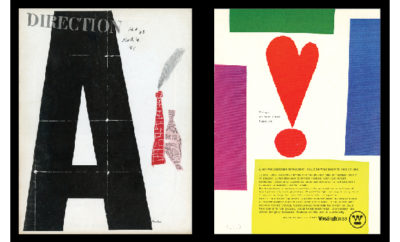

Clare Falkenstein with her kinetic sculpture Big Apple of 1948 in aluminum and Hydrocal. Photo courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, New York.

IN HER LIFETIME AND AFTER, Claire Falkenstein (1908–1997) was known as a sculptor, painter, and teacher as well as a ceramist and glass designer. Less is known about her stunning and dramatic jewelry, which has been exhibited only rarely, and not in many years. I became interested in her work about fifteen years ago when I bought one of her small “fusion” sculptures from a Chicago auction house. As I learned more about Falkenstein, I was astounded by her talent and facility with a range of materials. Each piece was distinctive, from her large sculptures in metal to her stained-glass windows to her jewelry—which I found particularly intriguing.

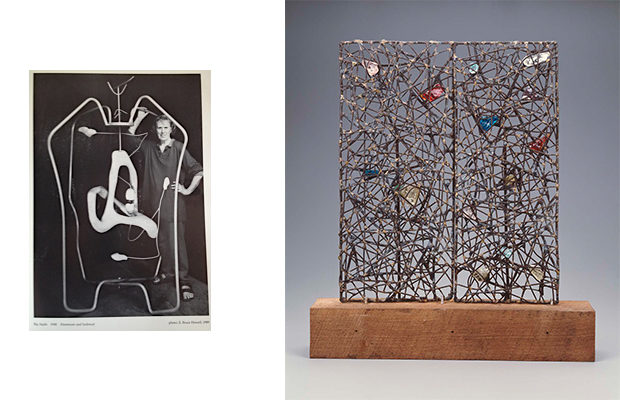

I am always interested in artists and industrial designers who “push the envelope.” Falkenstein explored new territory in both her jewelry and her sculpture. Each piece was unique, made by her own hands, and each more beautiful than the last. Falkenstein’s most famous work, The New Gates of Paradise, is a set of doors commissioned in 1960 by Peggy Guggenheim for her private palazzo (now the Guggenheim Museum Venice) on the Grand Canal. Each measuring nine by three feet, the doors are made of metal webbing into which Falkenstein placed large chunks of colored Venetian glass.

Falkenstein’s model for the gates she designed for the Venetian palazzo of Peggy Guggenheim, 1961, is made of painted copper wire and glass. Photo © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Born in Coos Bay, Oregon, Falkenstein received her B.A. in fine arts in 1930 from the University of California, Berkeley. She had her first gallery exhibition prior to graduating from college. Over the summer of 1933 she was exposed to some of the most avant-garde theories of the day by meeting László Moholy-Nagy and Gyorgy Kepes and through her studies at Mills College with sculptor Alexander Archipenko. She taught at a variety of schools and universities, honing her skills and developing her unique style through interactions with fellow teachers, particularly at the innovative California School of Fine Arts, where she taught alongside abstract expressionists such as Clyfford Still, who would become a close friend and artistic influence, and Richard Diebenkorn. During this period, Falkenstein frequently worked with carved wood and molded clay.

In 1950, believing that she needed new avenues of stimulation, Falkenstein decided to move to Europe. (She asked her husband to accompany her and when he refused, she divorced him.) From 1950 through about 1963, she lived in Paris, maintaining a studio on the Left Bank, where she met such artists as Jean (Hans) Arp, Alberto Giacometti, Sam Francis, and Paul Jenkins, as well as the art connoisseur Michael Tapié, who acted as a sort of mentor and promoter for the American expatriate community. Falkenstein found that her experience in Paris greatly advanced her artistic vocabulary and strengthened her foundation as a sculptor. During this period her work was shown frequently at the Galleria Spazio in Rome and Galerie Stadler in Paris.

Brooch by Falkenstein in silver. Bill Hibbs photo.

The rings, brooches, bracelets, and extraordinary necklaces Falkenstein fashioned were not maquettes for her sculpture. Instead, they were intended to be small wearable works of art. Her jewelry was shown at various prestigious exhibitions during her lifetime, including the second annual Exhibition of Contemporary Jewelry at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis in 1948 and the International Exhibition of Modern Jewelry in London in 1961. In 1962 the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris held a one-person exhibition of both her sculpture and jewelry.

From 1962 to 2004 her jewelry went relatively unrecognized. Not until 2004, seven years after her death, did the Long Beach Museum of Art in California have the insight and courage to mount The Modernist Jewelry of Claire Falkenstein, the most comprehensive exhibition of her jewelry to date. Maren Henderson, a co-curator of the exhibition, wrote in the accompanying catalogue: “Falkenstein cared very much about fit and comfort, and her works are a joy to wear. A piece of jewelry by Falkenstein however was never just an accessory. Falkenstein’s jewelry is not about costuming or fashion so much as formal ideas involving line, space, surface, materials, and color. Wearability and formal experiment become one and the same. The artist never pandered to the marketplace or fashion trends. Falkenstein looked more to the future, convinced that her work would find its time and place in history.”

Now, more than ten years since the Long Beach exhibition, I think it’s time that Claire Falkenstein’s jewelry be re-examined and enjoyed by a new generation. Her jewelry pieces are miniature sculptures, each unique and exciting, showcasing her talent and the numerous techniques she used.

In 1963 Falkenstein returned to Venice, California, where her work consisted primarily of large-scale commissions, such as the fifteen towering stained-glass windows that she created for Saint Basil Catholic Church in Los Angeles (1969), and Accelerating Point, a 1974 commission for the entrance of the San Diego Museum of Art.

A Venetian glass bead is incorporated into this gold-plated brass necklace of c. 1955.

Falkenstein started making jewelry in the mid- to late 1940s for numerous reasons, among them economy of scale and as a way to learn how to work with different metals. With jewelry, she was able to stretch her limited budget while taking risks and experimenting with different techniques. She practiced bending, welding, soldering, and casting metals—techniques she continued to use in her later sculpture and jewelry. In the 1950s, she used both glass and metal together, creating her “fusions.” At first she placed the glass chunks within her sculptures and jewelry, then later she melted the glass over the metal.

Note: After Falkenstein’s death in 1997, a group of her friends established the Falkenstein Foundation to expose and educate people about her work. Recently, the foundation became associated with the Michael Rosenfeld Gallery in New York to further promote her oeuvre.