The Gropius House in Lincoln, Massachusetts, completed in 1938. COURTESY OF HISTORIC NEW ENGLAND, ERIC ROTH PHOTO.

The Gropius House in Lincoln, Massachusetts, completed in 1938. COURTESY OF HISTORIC NEW ENGLAND, ERIC ROTH PHOTO.

Exhibition

Boston Goes Bauhaus

IF YOU LOOK AT THE COLLECTION OF WALTER GROPIUS’S OLD WORLD, formal bowties—his wife called them “brilliant little butterflies”—or the thick frames of his vintage black eyeglasses carefully displayed in front of a box of Leavitt and Peirce Cake Box Cigars at the Gropius House in Lincoln, Massachusetts, you might get the wrong opinion of the profoundly modern man who was the founder of the Bauhaus, the radical school of design that opened its doors in Weimar, Germany, in 1919. During the turbulent interwar period, Gropius’s forward thinking helped the Bauhaus survive in three German cities, moving from Weimar to Dessau to Berlin, each iteration testing out notions about unifying the arts and “unencumbering” architecture in order to adapt to the modern age with its assembly lines, radios, and speeding motor cars. Although the school was finally closed under pressure from the Nazis in 1933, Bauhaus ideas and teaching methods have survived to this day as the underpinnings of design standards, even if they often represent a point of departure or a springboard for resistance.

A desk-scape inside the Gropius House. COURTESY OF HISTORIC NEW ENGLAND, ROTH PHOTO.

When Gropius came to Harvard in 1937 to teach architecture, he managed to bring with him furniture from the Bauhaus Dessau (including the double desk Marcel Breuer designed for the director’s house and which is now in the Gropius House office), books, documents, and correspondence, as well as an innate capacity for adaptation. It didn’t take long for him to become an inspirational figure in the Boston area, where he spread his ideas about education, “unity in diversity,” and finding form through the resolution of practical problems. “Anything we do,” he would say, “we have to study the human being using it, a chair for instance, that is the starting point.” As he brought along fellow Bauhauslers— Breuer and Josef Albers taught at Harvard, and Herbert Bayer and Alexander Schawinsky often visited Gropius in Cambridge—his influence among students and young architects grew, and Boston became a hub of the Bauhaus diaspora. It’s no wonder that Boston is pulling out all the stops for the Bauhaus centennial.

Ati Gropius’s room at the Gropius House. COURTESY OF HISTORIC NEW ENGLAND, ROTH PHOTO.

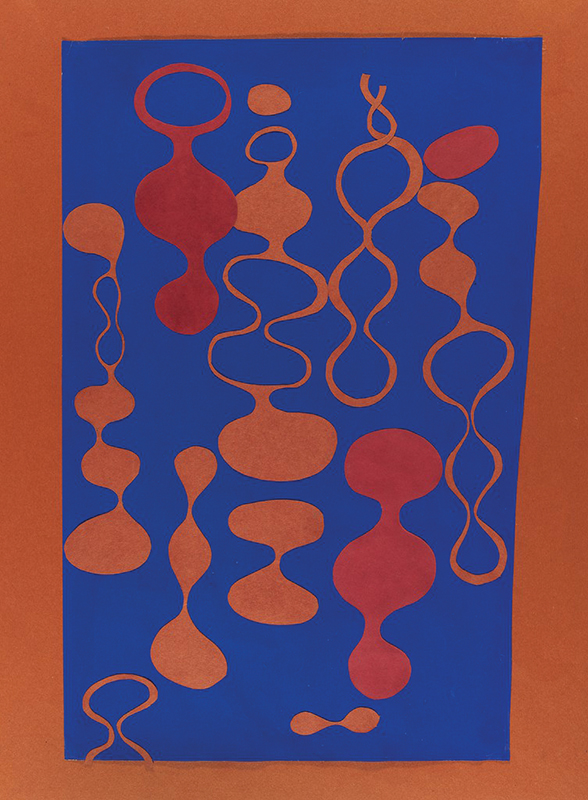

Among the many festivities planned in the Boston area in 2019 is The Bauhaus and Harvard, presented by the Harvard Art Museums, a meticulously curated show of nearly two hundred objects, primarily from its own enormous collection, that illustrate the protean nature of the Bauhaus idea as it developed and evolved. The exhibition contains many famous works, such as virtuosic drawings and wall hangings by Anni Albers and Wilhelm Wagenfeld’s coffee and tea service, handmade with brass and ebony fittings in the Weimar metal studio. Wagenfeld’s vessels—finely proportioned, modern geometric volumes—are completely unornamented on their surfaces and stand together in their stark simplicity like a miniature architectural grouping. The show also includes a unique sampling of compositional exercises by Bauhaus students and students of students. The artist Ruth Asawa, for instance, was working with Josef Albers at Black Mountain College when she experimented with color vibrations and patterning. In her brilliant collage of cut colored paper, organic shapes and empty loops float like lanterns or balloons on an irregular blue-painted rectangle affixed to orange wove paper.

Coffee and tea service by Wilhelm Wagenfeld, 1924–1925.

HARVARD ART MUSEUMS/BUSCH-REISINGER MUSEUM, GIFT OF HANNA LINDEMANN, © ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/VG BILD-KUNST, BONN; ALL HARVARD PHOTOS © PRESIDENT AND FELLOWS OF HARVARD COLLEGE.

Harvard has also installed the accompanying exhibition Hans Arp’s Constellations II. The thirteen shaped panels were originally commissioned for Harvard’s Graduate Center, which Gropius designed between 1948 and 1950, when he was still chairman of the department of architecture. Following the Bauhaus philosophy of integrating the fine and applied arts, he insisted that the architectural project include a budget for art, and he asked for work from Arp as well as Joan Miró, Herbert Bayer, Josef Albers, and Richard Lippold, an American sculptor who had trained in industrial design. Arp refined his composition of enormous, gravity-defying biomorphic shapes and stars on site, as he shifted around cardboard sample pieces cut to scale until he was certain they would complement the specific components of the Gropius- designed space. Mounted in the dining room of Harkness Commons, the wall reliefs were intended to demonstrate the way in which art and architecture could be fused—in the words of the Bauhaus manifesto, “in purposeful and cooperative endeavors.” But in time the work experienced the wear and tear that comes with use in a dining area; in 1958 the pieces were reinstalled higher on the walls as Constellations II and they were painted over in different colors over the years. After fifteen years in storage, the panels have recently been restored to their original stained redwood finish, highlighting the artist’s original intention to use natural and indigenous (indigenous to America, if not to Boston) material to transmit his dreamlike narrative of the constellations to Harvard.

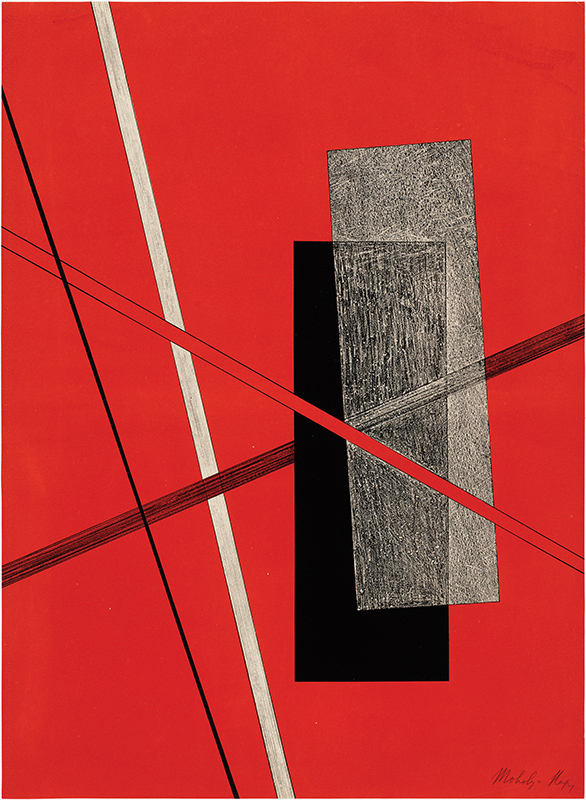

Untitled from Constructions: Kestner Portfolio 6 by László Moholy-Nagy, 1923. MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON, PROMISED GIFT OF RICHARD E. CAVES.

Across the river, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston is putting on two shows. Radical Geometries: Bauhaus Prints, 1919–1933 includes work by many Bauhauslers, including Lyonel Feininger, László Moholy-Nagy, Paul Klee, and Wassily Kandinsky. Kandinsky’s Kleine Welten (Little Worlds) suite is hardly ever exhibited as a whole, so it’s a great pleasure to see this small masterpiece comprised of four drypoints, four lithographs, and four woodcuts that play off one another like variations in a musical composition. Kandinsky’s clustered configurations of geometric shapes and biomorphic forms, squiggles, crosshatching, and tassels sometimes appear to float like boats in water and sometimes to explode like a confetti of space matter. The museum is also mounting Postwar Visions: European Photography, 1945–60, which explores how fundamental elements of the Bauhaus survived the ravages of World War II and gave direction to major photographers during the postwar period. Looking back to the Bauhaus’s beginnings, the MIT Museum is presenting the exhibition Arresting Fragments: Object Photography at the Bauhaus—ninety digital prints, architectural photographs, and photos of Bauhaus objects taken from Berlin’s vast Bauhaus Archive that cut across disciplines, demonstrating the way photography was used by Bauhaus artists to promote architectural projects and production pieces originating in the many workshops. Among the many striking images is Lucia Moholy’s photograph of Marianne Brandt’s tea infuser: a series of perfectly balanced, stacked volumes fills the picture frame, as if the object were a portrait, and every detail, from the distorted window reflected on the bowed silver surface to the dust collected on the lid, is lovingly recorded by the camera lens.

Constellations II by Hans Arp as the work was arranged in 1958 on the south wall and north wall of the Harkness Commons dining room at the Harvard’s Graduate Center. HARVARD ART MUSEUMS, TRANSFER FROM HARVARD LAW SCHOOOL, © ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/VG BILD-KUNST, BONN.

Certainly, the most spirited centennial event is planned for Walter Gropius’s birthday on May 18, with a Bauhaus-style birthday Metallisches Fest. Birthdays, costume parties, and ornately designed festivals (sometimes organized to help dissipate highly charged conflicts arising within the school) were a fundamental part of Bauhaus culture, and the 1929 Metallisches Fest was perhaps the most elaborate. Decorated with brass fruit bowls and Christmas ornaments, and with painted lights and mirror balls hanging from the ceiling and tinfoil covering the glass windows, the plaster and glass Bauhaus building glowed from the inside out. Guests, dressed in futuristic silvery costumes and metallic hats, helmets, or antennae, chuted down to the main foyer on a metal slide and danced to music played by the Bauhaus Band.

Kleine Welten IV by Wassily Kandinsky, 1922. MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON, BEQUEST OF W. G. RUSSELL ALLEN.

In 1970, the year after Gropius died, a thousand students and friends celebrated another Metallisches Fest in Cambridge as a memorial birthday party. This year’s party will take place at the Gropius House (a National Historic Landmark and a property of Historic New England), a modest jewel of modern architecture that Gropius designed, with Breuer as collaborator, for himself, his wife Ise, and their daughter Ati. On May 18 there will be the normally scheduled daytime tour of the house and an evening metal-themed garden party for visitors (encouraged to wear costumes) who purchase tickets in advance.

Design for a rug by Anni Albers, 1927. HARVARD ART MUSEUMS, GIFT OF ANNI ALBERS, © THE JOSEF AND ANNI ALBERS FOUNDATION/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK.

Like its émigré designer, the house optimistically carried the past forward. From the outside, its simple, massed rectangular forms and slightly sloping flat roof are reminders of the white interlocking cubes of the Masters’ Houses at the Bauhaus Dessau. At the same time, in acknowledgment of the New England landscape, Gropius chose to honor regional architectural traditions, using brick for the chimney, fieldstone at the foundation, and white-painted wood sheathing on the exterior— though the tongue-and-groove boards were applied iconoclastically, running vertically rather than horizontally. The house has garden party for visitors (encouraged to wear costumes) who purchase tickets in advance. Like its émigré designer, the house optimistically carried the past forward. From the outside, its simple, massed rectangular forms and slightly sloping flat roof are reminders of the white interlocking cubes of the Masters’ Houses at the Bauhaus Dessau. At the same time, in acknowledgment of the New England landscape, Gropius chose to honor regional architectural traditions, using brick for the chimney, fieldstone at the foundation, and white-painted wood sheathing on the exterior— though the tongue-and-groove boards were applied iconoclastically, running vertically rather than horizontally. The house has been called a laboratory for Gropius’s ideas for small house design. Efficient and economical (he ordered fixtures and appliances from catalogues and supply houses), it opens out to nature with the downstairs screened porch, the ribbon windows facing out to the garden and surrounding fields, and the upstairs roof deck providing a wider panorama. There are many lovely indoor touches: luminescent glass-block walls, cork tile in the entryway, and white clapboard interior panels, also set vertically.The streamlined, mantel-less fireplace and the organic sweep of the central staircase with its widely spaced polished chrome tubing create an elegance that seems to belie the fact that the house was built on a $20,000 budget and completed in little more than half a year.With a reduced palette of black and white and grays, and the simplicity of its light and portable tubular furniture, the house can be seen asa showcase for Bauhaus ideals, but it also resonates an intimacy and demonstrates the way good design emanates from consideration of the people who will use it. This is most obvious in the charming exterior staircase Gropius built for his daughter, who asked for a private entrance to her bedroom so her friends could come and go without formalities, or the way the screened porch accommodated a pingpong table that could be used for recreation during long New England winters. From room to room, there are countless intimations of the way the space and a family intertwined, and it’s a wonderful testament to an idea of modernity that’s now a hundred years old.