Design

When Modernism Met the Potter’s Wheel

CHICAGO CERAMIST EUGENE DEUTCH FOUND BEAUTY AND JOY IN THE “MODEST SIMPLICITY” OF CLAY

It’s hard to remember now the sheer joy of encountering handmade objects in the postwar years, when uniqueness and irregularity were so often undervalued. In Chicago, Eugene Deutch was a master potter of useful and classically modern bowls, lamps, plates, tumblers, vases, and pitchers, bucking the trend toward industrial mass production. Though he made pottery in large quantities and though there is continuous variety and experimentation in his work, his ceramics have a distinct style—rugged, tactile, and respectful of material, tradition, and function.

In his studio he was in charge of the entire production process, beginning with the selection of clays from Kentucky, New Jersey, Missouri, and Tennessee, which he churned in a pug mill adapted from a farmer’s feed grinder. He threw thickly potted shapes on a hand-built kick wheel, sometimes carving them as a sculptor, and he applied a wide range of vibrant glazes in earth colors such as gunmetal, cream, rust, granite gray, and chocolate, contrasted by luminous cobalt blue, aqua, gold, turquoise, and moss green. During World War II, he made ceramic cones for military airplanes and was able to acquire uranium for his glazes, expanding the colors to bright oranges and yellows that even today show up hot on a Geiger counter. He lamented that after the war and the explosions of atomic bombs, the mineral became unavailable.

Deutch created his own plaster molds for slip-casting biomorphic forms that complemented the shell-shaped chairs and kidney tables furnishing the architectural designs of the day. He was conscious of the challenge of fitting modern ceramics into informal and irregular living spaces. In his only published article, “Form in Ceramics,” he presented his thoughts in a charming way, “Often our free forms are off-round, and many times they have constant movements which make heavy clay jumpy.”

Deutch believed in the need to respect both the materiality of the clay and its “modest simplicity,” a philosophy that fit his dynamic but gentle personality. Like Bernard Leach and Shoji Hamada, who set up their famous studio at St. Ives, Cornwall, he was convinced that pottery should fuse art and design through an understanding of basic and universal principles: “Nature has created forms through evolutions, growth, and adaptations.” But Deutch’s character was more congenial than austere, and this led him in many directions outside his atelier. He played tennis, enjoyed chamber music, and was known for his legendary recipe for potatoes and eggs baked with paprika in sour cream and butter.

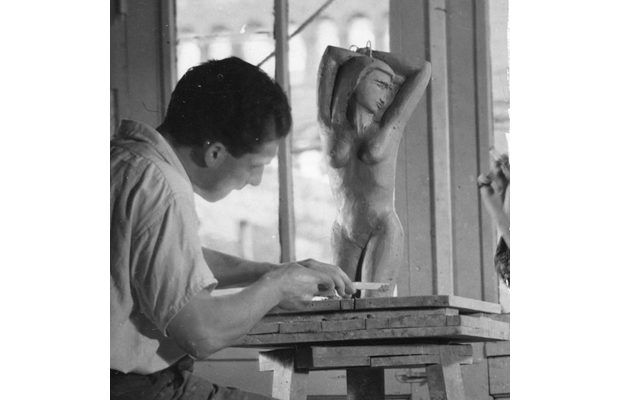

As an artist his influences were complex. He was born in 1904 into a working-class Jewish family in Budapest, a city with a tradition of folk pottery and ceramic decorative work. During his teenage years, he learned the trades of carpentry, cabinetmaking, and woodcarving. In 1923 he went to work in France, making his living as a carpenter in the factories on the French-German border and later in Paris, where he took classes in various crafts and sculpture. He was well aware of modern ideas about applied art and its relationship to folk art and architecture, factory production, and the problem of ornamentation, writing later: “In ceramics form has been misunderstood, and often completely forgotten, for the sake of decorative, surface expression.” In Paris he became friends with Constantin Brancusi, whose spirituality and thoughts about differentiating the essential from the ephemeral must have galvanized his own.

“I design to express something I feel and the result represents my best effort to create something decorative and functional,” wrote Deutch, a sentiment exemplified by this lamp of 1952. Aaron Wolf photo courtesy of Amy and Ken Wexler.

In 1927 Deutch arrived in Chicago, joining his brother Alfred, an artist who had a business specializing in handicrafts such as ceramics, wood inlays, and painted fabrics. Another brother Stephen, a photographer and sculptor, came to Chicago in the 1930s following Alfred’s death. Chicago was a crucible for broad and competing cultural ideas; the city had been one of the centers of the arts and crafts movement, and Frank Lloyd Wright had made his famous “The Art and Craft of the Machine” speech there, predicting that the machine age would bring simplicity and precision to works of art and alleviate the hardship of menial labor. But Deutch, who took classes at the Art Institute, was moving in the other direction, toward the model of the potter-artist whose handcraftsmanship would result in work that was responsive to “the inner needs of the material.” In 1934 he opened his own studio on Kilbourn Street, a year later moving his workshop to 923 North LaSalle Street, a garage off an alleyway where he made ceramic bowls, lamps, and pots as well as sculptural objects. Two of his pieces—a double vase pot and Nude, a terra-cotta figure—were selected for the prestigious Ceramic National exhibition in Syracuse, New York, in 1937.

During the Depression, Deutch was a member of the WPA and came into contact with many of Chicago’s outsized personalities—Ivan Albright, Nelson Algren, Studs Terkel—who hung out at Ric Riccardo’s restaurant and later at the Seven Stairs bookstore. The city’s grittiness was fortifying. Gallery owner Fern Simon, who carried work by Deutch for many years, calls him a renegade: “There was something defiant in his struggle, when you think of how hard it was to earn a living making pottery during his lifetime.” This determination is evident in an early photograph taken by his brother Stephen. Wearing splattered pants and a t-shirt, Deutch is poised in perfect symmetry at his kick wheel, hands and wrists washed in clay, the arms and chest of either a bricklayer or gymnast. Along with Myrtle Merritt French, he taught at Hull House Kilns, which served members of Chicago’s Mexican immigrant community, and with Stephen he made a trip to Mexico in 1938. The influence of the nationalist craft movement in Mexico with its idealized folk tradition is seen in the simple relief drawings—running horses or stylized birds—on Deutch’s handsome plates with unglazed edges.

Committed to making useful objects for domestic purposes, Deutch also taught at the Lewis Institute, home of the New Bauhaus, where Maholy-Nagy and Mies van der Rohe were on the faculty. He translated their ideas about honest treatment of material and form into straight-sided pots with semicircular “ears” for handles and handleless pitchers, pulled out at the rim and folded in at the shoulder so the glossy surfaces fit into the grasp of the pouring hand. In those pieces, bisque-fired first and then glaze-fired, his only ornament was the texture of the clay and the surface coatings, which he allowed to drip below the upper rim and pool into a contrasting color in the interior.

During the war years, American ceramic artists began struggling with their relationship to fine arts and the challenge of reconciling “necessary pottery” with self-expression. Deutch had always juggled his identities as a potter and a sculptor, and he continued to balance the two, sometimes casting fanciful figurines—little ducks for a daughter’s birthday party, for instance—as well as carving elegant human figures in clay. Probably his most innovative work is a hybrid of sculpture and pottery he developed in the 1950s, winning honorable mention in the 1955 International Exposition of Ceramics in Cannes. His beautiful, flaring Bird bowls (there may have been a hundred of them in all) have a heroic quality. The example now in the collection of the Milwaukee Art Museum swoops up like a composition by Brancusi or Arp. But the leathery, roughed-up skin of the unglazed exterior is scraped to allow the highlights of grout to show through, contrasting with the gleaming dark blue glaze of the interior. A simple object, it contains both self-assurance and grandeur and stands as a fine example of Chicago’s early avant-garde.

Deutch was one of the founders of Midwest Designer-Craftsmen, a group that promoted high quality design in both handmade and industrial work, but he was critical of the overly-glossy surfaces and the lack of personality in machine-made ware: “So many disinterested persons are involved in mass-production that the result is dead artistically,” he commented in a 1948 interview with the Dallas Morning News. But there were obviously fundamental problems for a potter-artist trying to put out useful objects one at a time in the age of industrial design.

Twice a year, at Christmas and Easter, Deutch would send out invitations for sales at his studio (which moved two more times as his family grew, first to a coach house at 12 West Maple in Chicago and then, in 1954, to 1419 Lake Avenue in Wilmette). He would purchase kegs of beer as enticement—“Buy a mug and fill it up”—and sell as many as a thousand pieces of thrown work. Otherwise, he showed with craftsman-artists (including Polia Pillin) at Merry Renk’s 750 Studio and Dorothy Rosenthal’s gallery in Chicago and he participated with designers such as Eva Zeisel and Russel Wright in exhibitions such as Useful Objects at MOMA (1946) and Useful Objects for the Home at the Akron Art Institute (1947), Chicago Potters’ Guild demonstrations at Marshall Fields (1948), and the US Designer-Craftsmen Show at the Brooklyn Museum (1953). A few prestigious retail shops carried his work—Artek-Pascoe in New York and Contemporary House Furnishings in Dallas.

Many of Chicago’s cognoscenti became his friends and patrons—Frank Lloyd Wright, the conductor Rafael Kubelik, University of Chicago president and chancellor Robert Hutchens, and the cellist George Sopkin. His work was exhibited at the Illinois State Museum in 1943; in a solo show at the Dallas Museum of Art in 1948; at the University of Chicago’s Renaissance Society in 1953; and, after his death, in a retrospective at the Art Institute in 1959. Today his work is owned by the University of Chicago’s Smart Museum, the Dallas Museum of Art, the Milwaukee Museum of Art, the Chicago History Museum, and the Racine Art Museum.

These Bauhaus-inspired bowls date between 1946 and 1952. Courtesy of Fern Simon, Arts 220.

Occasionally Deutch’s work comes on the market when the households of his contemporaries are disbursed. It is still collected, especially by people who value mid-century architecture—it looks right at home in photographs of a Chicago area Keck and Keck house or Wallace Neff’s Shell House in Pasadena. Framed in space and displayed as a group, his pieces tell a beautiful story about the search for what was essential at a seminal moment for modernism.