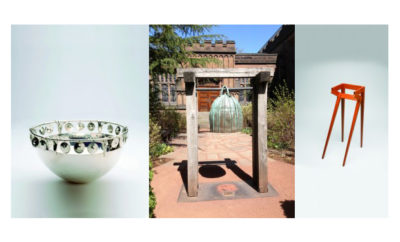

Gabriella Kiss and Chris Lehrecke, Christopher Kurtz and Deborah Ehrlich. Photos courtesy of Gina Dambra photo and Willa Kurtz.

Gabriella Kiss and Chris Lehrecke, Christopher Kurtz and Deborah Ehrlich. Photos courtesy of Gina Dambra photo and Willa Kurtz.

Feature

Two by Two

THE HUDSON RIVER was an essential corridor for industry in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and along its banks and a few miles inland were brickyards, whaling ports, and cement and ironwork factories. But with new technology and advancements, many of these industries died off. In recent years, the abandoned warehouses and factories have been transformed into art centers and exhibition spaces. Dia: Beacon renovated the 300,000-square-foot Nabisco box-printing facility in 2003, and a few years later, the Wassaic Project was born in the old Maxon Mills building. In the last year, Etsy, the e-commerce site for crafts and design, opened an office in the Cannonball Factory in Hudson. As it emerges from its post-industrial slump, the Hudson valley has also beckoned to designers and artists.

This cultural resurgence isn’t limited to one town or a single county. It lives on both sides of the river, stretching from Newburgh up to the area surrounding the town of Hudson. There are a few simple and obvious reasons behind the region’s burgeoning arts community: the close proximity to the city, the abundance of affordable real estate and studio space, and then, the beauty of the landscape. For many New Yorkers, the region (just two hours out of the city, give or take) has long been a weekend and summer destination, but in the last decade, many have traded in their apartments in the city for houses in towns where the arts and cutting-edge design are flourishing. The sidewalks of Hudson are dotted with twentieth century design shops and galleries, including Ornamentum Gallery of International Contemporary Art Jewelry, modernist furniture dealer Mark McDonald’s eponymous shop, and the gallery and store of furniture designer Chris Lehrecke, about whom you’ll learn more in the following pages. Last May the performance artist Marina Abramovic revealed her ambitious design plans, conceived by the partners Shohei Shigematsu and Rem Koolhaas of Netherlands-based architecture firm OMA, to turn a former theater in Hudson into the Marina Abramovic Institute for the Preservation of Performance Art. This new center will be a welcome addition to a region that is rich in performance art venues, from the striking Frank Gehry-designed Richard B. Fisher Center at Bard College to the Basilica Hudson, a nineteenth-century factory-turned art- and performance space where artist and musician Patti Smith once took the stage.

The four designers featured here—who happen to make up two couples—came to the Hudson River valley for an array of reasons, from the need for space to the contemplative landscape. It has proven to be a fertile ground for design and innovation.

Gabriella Kiss

GABRIELLA KISS HAS AN EYE FOR DETAIL. Each piece of jewelry she designs is a small sculpture that fits within a larger allegorical framework. Much of her work draws from nature and the beauty of the materials and her surroundings. Most recently, she has been working on a mushroom collection, casting these fleshy, umbrella-shaped organisms in gold, silver, or bronze and then making them into earrings, brooches, and necklaces embellished with golden slugs and precious and semiprecious stones. When looking at these pieces, it is nearly impossible to imagine that those golden fans were once mushrooms. But then that is the point. There is something lovely about what is often overlooked or deemed less desirable. And in this case, she is responding to how society views aging. “I am always aware of how there is beauty in decay,” Kiss says. “I love tulips the best when they are just on their way out, about to curl.”

Jewelry usually has its own narrative, which is what appeals to Kiss about the craft. It can be something that is passed down through generations or shared on special occasions. Kiss’s grandparents came from a peasant background in Hungary, and so there was very little jewelry in the family, but she always remembered the tiny golden walnut her grandmother wore around her neck, which had been a gift from her grandfather (the family name was Nuss, which means “nut”). The necklace disappeared, but Kiss created an entire series based on that one memory.

From a young age, Kiss enjoyed working with her hands and always had “an affinity for the small scale.” At the time she arrived at Pratt Institute in the late 1970s (she graduated in 1980), modernist jewelry was just having a resurgence: Ted Muehling and Elsa Peretti were receiving a lot of press. Kiss designed her own jewelry major within the sculpture department, and when she graduated she called Muehling and asked for a job. The timing was perfect. He needed help for a show that he was working on in Paris and brought her on board. As an apprentice and assistant to Muehling, she honed her craft, and after eight years working in his studio, she went out on her own.

Kiss’s studio is located in a nineteenth-century house across the street from the renovated church where she and her husband, Chris Lehrecke, live. The couple moved to the Hudson valley about fifteen years ago. They work in separate studios, but will soon join forces and collaborate on a show to be presented by Ralph Pucci next year. The scale of their work couldn’t be more different, but their perspectives often complement one another.

“If we travel together, Chris can see the big picture of things. Architecture for instance, he’ll see the whole building and I am always focusing on the details,” Kiss says. “But I think that part of what I am trying to get at in my work is that the microcosm is the macrocosm. There is a whole world inside of the details.”

Chris Lehrecke

CHRIS LEHRECKE’S STUDIO, perched on a hill behind his and Kiss’s house in Bangall, New York, is where he spends most of his days designing furniture. It is more than a studio—it is a large self-contained facility that houses everything from the milling of wood to the production of furniture, as well as a showroom and offices. It is a place where a master craftsman, like Lehrecke, can flex his imagination and expand his technique all under one roof.

He is influenced by a hybrid of styles—such as Shaker, African art, and Scandinavian design—but has cultivated his own aesthetic that is cohesive, distinct, and unquestionably modern. Living in the Hudson valley with its abundance of hardwood trees has provided an ideal set-up to acquire the materials he needs to produce some of his signature pieces. He finds much of his wood through loggers and local tree removal companies, who will call him when they have something that might be of interest to him. The trees Lehrecke collects might have imperfections, but for him, that is part of their charm. “They are not always veneer quality logs but that doesn’t bother me,” he says. “I love trees that have character or trees that have no commercial value at all.”

While he often uses walnut or ash for his pedestals, he’s not afraid to design pieces with unusual or less popular woods, such as catalpa or butternut. If he had his druthers, he would take a different approach to selecting materials. “I wish I could run it more like a restaurant and tell people what is in season,” he says.

Lehrecke discovered design in his twenties when he started working for a furniture maker in Brooklyn. The 1990s proved to be a good time to enter the field—it was a period when his design sensibility seemed to line up with the demands of the market. After living in Brooklyn for many years, he and Gabriella decided to move to the Hudson valley. It was around the same time that he forged a relationship with the Ralph Pucci showroom, which has provided an important outlet for his work.

In recent years Lehrecke also has collaborated with E.R. Butler and Company to create a collection of cabinet pulls. The scale is smaller, but the work still reflects his personal style and shares a likeness in form to his Totem collection of sculptures presented at Pucci two seasons ago. “There is this signature and language I developed early on that I felt really good about,” Lehrecke says. “I don’t feel like I am changing radically or drastically every few years. I am expanding on an already existing way of designing and looking at things.”

And though he has a well-articulated style, it never translates the same way: each piece of furniture conveys a stroke of imagination.

Deborah Ehrlich

DESGINER DEBORAH EHRLICH and her husband, artist Christopher Kurtz, often joke that one of her callings might be arranging the hay bales on the fields right off the road. And, in fact, Ehrlich once approached a farmer and asked if she could position the bales on his property as if composing a painting on canvas. Responding to the landscape, she placed them in various points on the field, creating a temporary art installation. This might sound unorthodox, but it fits with Ehrlich’s design sensibility, one that is driven by interaction with the everyday objects in our environments.

Whether large-scale or miniscule, her work is experiential, and the thought process is much the same. And yet, when designing her crystal glassware or hurricane lanterns, she marks the paper with exact points and measurements. It comes down to intuition, but it is the subtle and precise accents that make a difference in the relationship between the person and the object, and between the object and the setting. “I wanted to do things that you could interact with physically, and in the end, a lot of the work that I am doing does that,” Ehrlich says. “I imagine myself like a miniature and these [her glassware] are buildings.”

Ehrlich, Kurtz, and their daughter Willa live in an eighteenth-century stone farmhouse in the bite-size town of Accord, New York, on the west side of the Hudson. Her studio occupies a large space on the first floor. Delicate stemware and hand-drawn sketches sit on top of the long farm table that serves as her worktable.

Born and raised in New Jersey, Ehrlich moved to New York City to attend Barnard College. Her interest in sculpture took her to Kentucky to study with sculptor Mike Skop, but it was her time as a guest student at the Danish Design School in Copenhagen when she really became immersed in design and glass production. “I sort of fell backwards into design because I was interested not in becoming a designer, but because I was interested in the process,” she says.

When Ehrlich returned from Europe, she took a trip upstate and fell in love with the area and decided to stay. But more than a decade later, she is still connected to Scandinavia. The design work takes place in her studio, but the fabrication happens in Sweden by a master molder and glass blower. “A lot of my work can be difficult. I tend to create designs that maybe have angles that are not the most comfortable,” she says. She might test the limits, but in the end, it is always worth it. “The fun part about design for me is working with people,” she says. “It gives me this sort of poetic challenge.”

Christopher Kurtz

YOU CAN CALL CHRISTOPHER KURTZ an artist, a furniture designer, and a sculptor, but his vernacular is wood. His sculptures can twist and unravel with a fluidity that almost defies the nature of the material. But then, he can also mold and tame the wood to form sharp points and angles—as he managed to do for the legs of his Quarter Round side tables and for a recent installation that he had suspended from the ceiling. His technical skill gives him the freedom to move back and forth between sculpture and furniture. But Kurtz was a sculptor first, and when he was in art school these two worlds rarely, if ever, overlapped. “It took me a few years after leaving art school to get rid of those boundaries that they sort of impose on you and realize that those things don’t work against each other. I can make sculpture. I can make furniture. I can make art furniture. It can all happen under the same roof,” Kurtz says. “All those things can buttress one another.” Furniture wasn’t a stretch for him. His work had always been hands-on and labor intensive, and as he continued to experiment with wood he naturally gained the kind of experience that he needed to make furniture. In both disciplines, a sense of movement and form defines his work—exuding a kinetic energy.

Kurtz works out of a small workshop on the property right next to the house. Hailing originally from rural Missouri, he ended up in the Hudson valley when he landed an assistant position with American sculptor Martin Puryear. Kurtz found a mentor in the celebrated artist, whose work often melds craft and sculpture. While apprenticing for Puryear, he met Ehrlich at the local deli. The two had mutual friends, but until that afternoon, they had never crossed paths. The rest, as they say, is history.

After five years with Puryear, Kurtz decided to focus on his own work. Since then, his sculpture and furniture have been featured in several exhibitions, including a recent one-man show entitled Longhand at Tomlinson Kong Contemporary in New York City. This winter Hedge Gallery in San Francisco will present a solo show of his work.

By limiting his choice of materials to mostly domestic woods such as white oak, ash, and basswood, Kurtz says he has expanded his range. There’s a duality that exists within the wood itself that appeals to him and is also reflected in his work: a controlled chaos that is created by the marriage of organic forms and structure. “The material is very alive but it is also very rigid,” he says. “There’s just something about how the material behaves that matches my temperament really well. At some point I just decided to learn from working with the language and be as fluid with it as possible so I could go and say whatever I wanted to.”