The global headquarters of Bacardi Limited, located in Hamilton, Bermuda, was erected in 1972 from Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s unused 1957 plans for the firm’s headquarters in Santiago de Cuba. Photography by Véronique Mati

The global headquarters of Bacardi Limited, located in Hamilton, Bermuda, was erected in 1972 from Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s unused 1957 plans for the firm’s headquarters in Santiago de Cuba. Photography by Véronique Mati

Feature

Building Bacardi: Architecture, Art & Identity

BACARDI, THE FAMED SPIRITS COMPANY BEST KNOWN FOR ITS TRADEMARK RUM AND ITS BAT LOGO, was a powerful protagonist of modern architecture. The company was an avid builder, especially in the twentieth century, when extraordinary growth drove it to commission industrial and administrative campuses, urban towers, bars, and even museums. Founded in Santiago de Cuba in 1862, Bacardi rose from humble beginnings as a regional rum distiller to become a global industry. By the early twentieth century, as it acquired wealth and prestige during the consolidation of the Cuban Republic, the company began to attach symbolic and cultural importance to its buildings, commissioning major works that reinforced its identity as an iconic Cuban brand and nurtured an emerging position as a patron of the arts.

The 1930 Edificio Bacardi, an eleven-story art deco tower in the heart of the Cuban capital, was an important marker of this early patronage and remains a powerful symbol of modern Havana. Topped by a stepped pyramid and crowned by a bronze Bacardi bat, its ornate and polychromatic facades — composed of granites, marbles, brick, and glazed terra cotta in colors ranging from ocher and sienna to white, yellow, and cobalt blue — created a striking iconography that blended civic art and metropolitan ambition.

The Edificio Bacardi was notable for its evocation of the corporate towers rising in New York, Chicago, and even Miami — especially those inspired by the stepped massing of the Giralda tower of Seville’s cathedral. Though the art deco sensibility came to fruition in the built tower, a Renaissance revival style design by architects Esteban Rodríguez Castells and Rafael Fernández Ruenes had actually won the invited competition organized by the company in 1927. Much of the decorative syntax and fantastic imagery are attributed to American illustrator Maxfield Parrish, whose pairing of geometric forms and playful human figures articulated friezes that wrap the building. On the inside, an unrestrained use of polished stone, brass, etched glass, and gold leaf, offset with precious woods and muted colors, greeted — and astonished — visitors. The tower’s legendary art deco executive bar engaged in “experience marketing” to thirsty celebrities and tourists from Prohibition-era United States. Mixing Cuban rum and swank styling, the bar embodied the Bacardi slogan, “The One That Has Made Cuba Famous.”

Experimenting with modern planning and architecture in the postwar era, the company developed new campuses in the Caribbean and Mexico. The first was built in 1946 on the Palo Seco peninsula facing Old San Juan, Puerto Rico, starting with a distillery designed by W. Donald Christie, a modern classical structure that incorporated an internal distillery column within its five-story central tower. Around this “Cathedral of Rum” (as territorial governor Luis Mu-ñoz Marin called it), Puerto Rican and Cuban architects, including Toro Ferrer, Stephen Arneson and Henry Klumb, Rámon M. Benitez, and SACMAG of Puerto Rico, developed an industrial campus remarkable for its diverse modern vocabulary: corrugated concrete roof forms expressed in projecting trapezoidal gables; bat-winged concrete shells based on hyperbolic paraboloid forms; an apsidal array of concrete barrel vaults; and concrete butterfly roofs.

Bacardi initiated a second modern campus near Puebla, Mexico, in 1955. Here, the Spanish émigré Félix Candela (and his company Cubiertas Ala), working with Mexican architects Hector Mestre and Manuel de la Colina and the Cuban engineer Luis P. Saenz (of SACMAG), produced a variety of purpose-built structures, ascetic solutions to the functional problems of a distillery. The plant was built on the site of the seventeenth-century Hacienda La Galarza and, remarkably, incorporated its rustic brick and stone walls, arches, vaults, and even a small chapel, to create a sublime contrast between pastoral and industrial.

The ambition and scope of Bacardi’s postwar growth cannot be dissociated from the personality of Jose “Pepin” Bosch, the firm’s third president. A preview of Bosch’s taste for architectural adventure can be seen in his 1956 commission to design a beach house in Varadero, Cuba. Philip Johnson’s unbuilt project proposed a pavilion-in-the-round, a prismatic form rising to a vaulted, polygonal roof system formed in concrete.

In 1957 Bosch commissioned Ludwig Mies van der Rohe to design the Bacardi administration building in Santiago de Cuba. After visiting the architect’s S. R. Crown Hall in Chicago, Bosch wrote to him, “My ideal office is one where there are no partitions, where everybody, both officers and employees, are seeing each other.” Mies van der Rohe designed a monumental glass and concrete pavilion that emphasized universality, transparency, and order — the very corporate principles that Bacardi wished to transmit to an increasingly global public. He envisioned a single great room bound by plate glass and bronze mullions and subdivided by low marble walls. To deal with the Caribbean sun, the roof was to incorporate a continuous overhang supported on eight peripheral columns. Although the volatile political circumstances in Cuba in the following few years prevented building from going forward, the commission made headlines in the international architectural press and propelled the cultural status of Bacardi.

To complement the distillery at La Galarza, Bacardi developed a second facility in Tultitlán, along the Central Highway leading north out of Mexico City. If Galarza was a romantic landscape, Tultitlán was a modern, functionalist one. Félix Candela was again paired with SACMAG, and with Luis Torres Landa, a Mexican engineer. Candela produced a large variety of concrete-shell structures for this facility, employing groin vaults, barrel vaults, umbrellas, and folded-plate slabs. The lead figure in this cast of shell forms was the cavernous groin-vaulted bottling hall. Partly inspired by the recently completed Lambert-St. Louis Airport Terminal (1956) by Minoru Yamasaki and Anton Tedesko, Candela reinterpreted Lambert’s intersecting barrel vaults using hyperbolic paraboloids, whose double-curved surfaces achieved a thinner, lighter structure. Around the bottling hall, Candela developed warehouses, parking structures, and even housing using row upon row of straight-edged “umbrellas,” a modular system that also used hyperbolic paraboloid shells developed by Cubiertas Ala.

In 1959 Bacardi turned again to Mies van der Rohe with a commission to design Tultitlán’s administration building. The open plan idea for Santiago found a different synthesis in Mexico: a broad rectangular raised floor centered on an open void connecting to the ground level. In contrast to the concrete and granite proposed for Santiago, here Mies van der Rohe returned to his more usual formulation of an exposed steel skeleton (painted black), gray-tinted plate glass, and travertine flooring. Separated from the industrial works, where Candela used expressive concrete forms in repetition to form crystalline patterns, Mies van der Rohe’s building sat in a park-like garden, a black pavilion of monumental singularity and cool corporate abstraction.

The 1959 Cuban Revolution and subsequent nationalization of the company’s Cuban assets in 1960 forced a break point in Bacardi history but not in the production of new buildings. In a show of strength in the face of existential crisis, Bacardi replaced its pre-revolution capacity in new centers spread throughout the hemisphere and developed a Pan-American identity. In 1963 the firm shifted its American arm, Bacardi Imports, from New York to Miami, which, four years after the Cuban Revolution, had become home to hundreds of thousands of exiled Cubans. With its own recent exile, the move was a bold statement of endurance and social solidarity.

The Miami Bacardi Imports Tower, designed by Cuban exile Enrique Gutiérrez of SACMAG, was a simple, daring, and monumental statement. The slender seven-story tower along Biscayne Boulevard stood atop a raised and landscaped plaza (a reference to Mies van der Rohe’s recently-completed Seagram Building in New York). It employed an exoskeletal structure in which the floors were hung using a system of cables and pulleys from trusses supported on only four marble-clad piers. The system allowed an exceptional lightness and transparency at the ground floor, where a public art gallery known as “The Bacardi” opened onto the plaza. The tower’s most radical feature was its hybrid skin of plate glass and colorful tiles.

Bosch directed the development of narrative murals inspired by the Mexican mural movement, specifi-cally by the recently completed Central Library of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (1956), covered in exquisite murals by architect and muralist Juan O’Gorman. The Miami murals were designed by Brazilian artist Francisco Brennand, who overlaid the tower’s end walls with azulejos, glazed ceramic tiles, forming designs of abstract flowers in the Portuguese colors of blue and white. The Brazilian identification was quickly naturalized to represent both tropical Miami and Bacardi. The blending of the modernist curtain wall and the sensuous, larger-than-life floral tilework seems to encapsulate the company’s eclectic and hybridizing approach to modern architecture.

Two other works of the 1970s can be considered part of the Bacardi architecture story. The first, the Bacardi Imports Annex, designed by Miami architect Ignacio Carrera-Justiz, sprouted mushroom-like from the plaza behind the Miami tower in 1973. The building’s cantilevered office floors hang from a grid of post-tensioned beams in the roof. The walls, vitreous tapestries of colored glass, translated a series of four commissioned artworks by the German abstract artist Johannes Maria Dietz that feature figures of bats and thematically illustrate the conversion of sugar cane into rum.

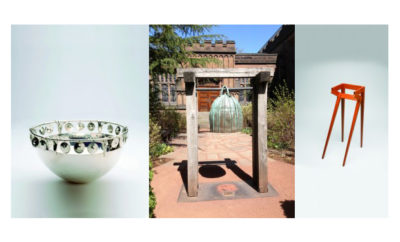

The second was the company’s new administrative headquarters in Hamilton, Bermuda, completed in 1972. As an act of defiance and/or nostalgia, the company here erected Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s unbuilt 1957 project for its Santiago de Cuba headquarters, incorporating collective memory into a physical symbol for the company.

If the architectural works of Bacardi form a narrative, it is striking how diverse this narrative can be. The company freely experimented using a range of modern expressions, from rationalist to expressionist, from everyday to exotic; it explored varied urban and cultural contexts, discrete industrial and corporate landscapes, and the conceptual choices of leading architects. Moreover, Bacardi challenged notions of modern architecture as a purely rational enterprise or as a standardizing force; here, in the service of a transnational corporation, it evolved as a consistently site-specific, culturally attuned, and narrative art.