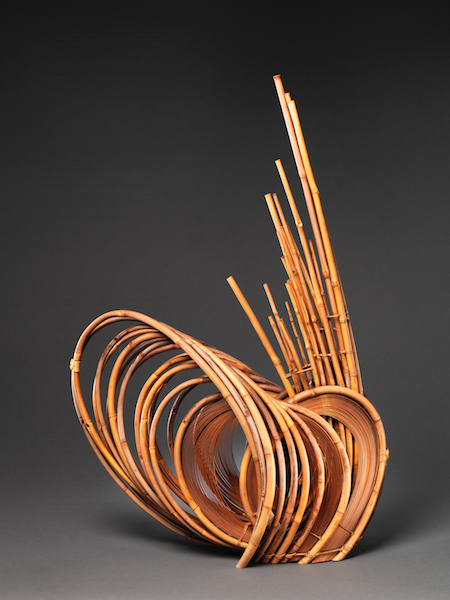

The Gate by Tanabe Chikuunsai IV, 2017. Courtesy Tanabe Chikuunsai IV

The Gate by Tanabe Chikuunsai IV, 2017. Courtesy Tanabe Chikuunsai IV

Exhibition

Twists and Turns in Bamboo: The Abbey Collection at the Met

To honor the opening of Japanese Bamboo Art: The Abbey Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, Tanabe Chikuunsai IV, the scion of an esteemed line of bamboo artists, constructed a spectacular on-sight installation with a team of assistants, weaving thousands of bamboo stems into a fragile membrane. The Gate (Mon) rises up in the shape that brings to mind the outstretched boughs of a Japanese maple, its woven surfaces growing out of the ground like exposed roots, then twisting, turning, and attaching itself to walls and ceiling. From certain angles, the surfaces look like the crisscrossing of dried straw left in a field and from others they seem covered with the multiple layers of the constellations. In a totally contemporary way, the piece, which is both sculptural and architectural, epitomizes a core concept of traditional Japanese bamboo weaving: by working respectfully with the esteemed material, artists can create another universe.

The Met show (it is on view through February 4) is an expansive exhibition, focusing on modern Japanese bamboo art which began in the late-nineteenth century when Hayakowa Shōkōsai I became the first Japanese artist to inscribe his signature onto bamboo basketry, taking credit for his compositions. When you look at those early examples of the craft, you understand immediately how concentrated observation of nature was a foundation for the discipline, and the baskets themselves, sometimes lidded and sometimes open like vases, were microcosms for the world that surrounded them. Traditional, formal, and symmetric basketry style–based on the model of objects imported from China for the tea ceremony– demonstrated a virtuosity of plaiting as meticulous as tapestry. Shōkōsai famously showed off his consummate skill through a humorous dalliance with western culture, making a series of English-style bowler hats from bamboo and rattan trimmed with braided silk.

Bowler Hat by Hayakawa Shōkōsai.

In the early part of the twentieth century, the artist Iizuka Rōkansai codified a theory of three modes of basketry corresponding to three different settings for daily life: the refined, aristocratic style; a looser approach that would be appropriate for informal situations, perhaps at a summer tea table set out of doors; and a rustic, more modern-seeming mode, intended to demonstrate the natural beauty, imperfections, and harmonies one might find in the accidental and humble beauties of the countryside. Like Western sculptors who were experimenting with abstraction and the complexities of geometric and organic shapes, Rōkansai was interested in the tension between irregularity and balance as it could be played out through the configuration of bamboo boxes, baskets, and vases. In the Abbey Collection, you can see the more relaxed style of his loosely woven and elongated flower basket, ca. 1932, that rises more than forty inches high with the graceful verticality of an opening iris.

Rōkansai’s son Iizuka Shōkansai, went further in experimentation with the craft, inventing his own procedure for splitting, pounding, flattening, and cutting long pieces of bamboo, while leaving tiny connections. He would use his entire body to shape and weave the bamboo as he did in his Dragon in the Clouds Flower Basket, from 1990, which is a centerpiece of the Met exhibit, exposing the beauty of the bowed and intertwining bamboo as well as its tensile strength. For Shōkansai there was a direct link between the struggle of working with the strong and resistant material and his own credo; everything he created was premised on use, finding completion when a lid was opened or flowers were placed inside.

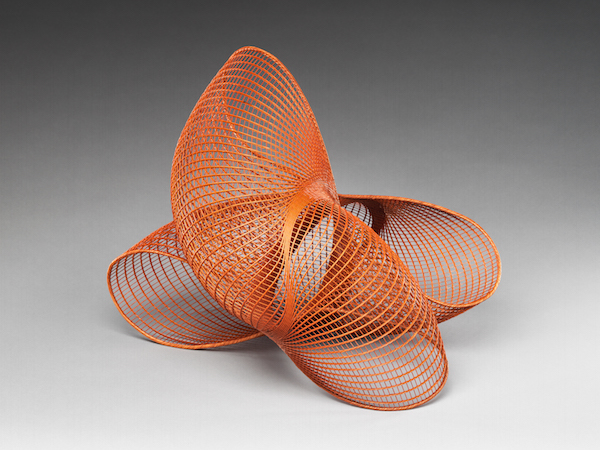

Dance by Honda Shōryū, 2000. Courtesy Honda Shōryū

Other artists of his generation turned in another direction, integrating fine arts into the tradition of applied arts, working to express their own individuality. Honma Kazuaki, for instance, coaxed bamboo into organic turns and curves for his splendid 1968 composition, Breath, teasing the material to form taut spirals and then pulling up the ends into what looks like the comb-like configuration you might see in a sculpture by Julio Gonzalaz. This unabashedly and intentionally sculptural piece explores form and emptiness, carving out a passageway for wind and light.

Those same formal concerns are addressed by the contemporary artist Honda Shōryū who twists, long thin twines of woven bamboo to form a netting that he shapes organically, removing his basketry from the basket and liberating his shapes to float in space. Shōryū’s piece, constructed in 2000, is entitled Dance, with two connected and complementary sections that mirror one another like partners in a dance. One might think of it as a metaphor for the craft and art of bamboo, a world hinged together, both inside and outside of tradition.