Feature

The Stoller Mystique

A new book, Ezra Stoller, Photographer, from Yale University Press, gives the master the prominence he deserves.

Interior of Saarinen’s TWA Terminal of 1956–1962 at Idlewild (now JFK) Airport, Queens, New York, photographed 1962.

AMONG THE ADVANTAGES OF GROWING UP ON LONG ISLAND in the middle of the twentieth century was proximity to the creative cauldron of New York City. Instruction in modern art and architecture, for example, did not come from books: it was all show and tell. There were field trips to the Guggenheim when it was new and to the inaugural week of Lincoln Center’s Philharmonic Hall. The cities of my adolescent imagination and limited drafting prowess were full of impossibly high Lever Houses, futuristic A-frame cathedrals, and homages to Morris Lapidus’s Americana Hotel (now the Sheraton New York), which boldly went where no building had ever gone before—off the strict right-angle orientation of Midtown Manhattan’s street grid.

While I was busy learning what modern architecture was, Ezra Stoller, a gentleman several decades my senior, was recording it on film. Stoller was born in Chicago in 1915, took a degree in industrial design from NYU in 1938, and soon thereafter set about becoming one of the world’s first architectural photographers. Sometimes known as the “East Coast Julius Shulman,” a comparison to the better known photographer who recorded the history of California modernism, Stoller stayed in New York. He worked notably for Architectural Forum magazine but for other magazines as well, and also collaborated with architects and their clients.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum of 1959, New York City, photographed 1959.

Stoller, however, was no point-and-click assignment shooter. He would study his subjects for days, sometimes longer, in order to discover not just the spirit of the buildings but the best way to render them. Consequently his work is known for its sophisticated lighting and unexpected points of view. Working with large format cameras and almost always in black-and-white, Stoller documented such now iconic buildings as the United Nations, Wright’s Fallingwater, Eero Saarinen’s game-changing TWA Terminal, Philip Johnson’s Glass House, even Le Corbusier’s Notre Dame du Haut.

Stoller was not just taking visual notes; he was composing two-dimensional symphonies. His images transcend photojournalism in the same way architecture floats on a higher aesthetic plane than more prosaic building. Taking his cues from abstract expressionism and other modernist works as inhabited the Museum of Modern Art, Stoller became a first-rank artist in his own right, whether he was documenting public icons, private houses, or the world of industrial production. For his efforts, he was awarded the first-ever gold medal for architectural photography, created by the American Institute of Architects in 1961.

Stoller’s photographs do not look complex, yet the strategies are sometimes breathtaking. A detail shot of the Seagram building’s facade occupies only the left half of his frame; the right is occupied by the urban context of Mies van der Rohe’s black monolith, including much of Lever House across Park Avenue. A shot looking out from the glazed lobby of Pietro Belluschi’s Equitable Building in Portland, Oregon (now called the Commonwealth Building and one of the first steel-and-glass high rises), shows the neoclassic wedding-cake masonry of the U.S. National Bank Building of 1921 across the street. Most of what you need to know about modern architecture is contained in the image—with a nod to the paintings of Mondrian.

Interior of Marcel Breuer’s Whitney Museum of American Art of 1966, New York City, photographed 1966.

In fact, looking at Stoller’s photographs in the new Yale University Press monograph, Ezra Stoller, Photographer, connections to a museum’s worth of artists rise off the pages. Stoller’s nighttime shot of Marcel Breuer’s 1966 Whitney Museum of American Art alone is redolent of de Chirico’s mystery, Hopper’s lighting, and the geometries of Rothko rendered in sharp-edged stone rather than soft-focus pigment. There’s something of the bold wide-brush slashes of Franz Klein in the girders of Stoller’s in-progress shots of Skidmore, Owings and Merrill’s Hancock Center in Chicago. And there’s something of Bernd and Hilla Becher’s black-and-white shots of nuclear reactors and oil tanks that seem inspired by images like Stoller’s exhaust fans on the roof of the Reynolds Plant in Arkansas or the water tower of the General Motors Technical Center in Michigan (both taken in 1955).

From “Power in the West” for Fortune magazine.

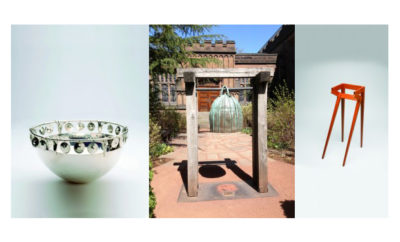

The book also contains photos of two of Yale’s landmarks: Paul Rudolph’s 1963 Art and Architecture Building and Eero Saarinen’s matched pair of residential colleges (1962). The authors are architecture critic Nina Rappaport and Erica Stoller, who runs Esto, the agency and archive founded by her father, with additional essays by Andy Grundberg, John Morris Dixon, and Akiko Busch. In addition to celebrating Stoller’s architectural imagery, the book includes his considerable industrial photography. Stylistically, Stoller’s take on the means and methods of production takes more than a casual cue from Russian constructivism. It’s clear that he was constantly trying to expand the implied limits of his medium.

Interior of Philip Johnson’s New York State Pavilion at the 1964–1965 World’s Fair, Queens, New York, photographed 1964.

The time line of the photos included begins with Alvar Aalto’s 1939 World’s Fair pavilion for his native Finland, which echoes the curves of his iconic free-form glass vase. The most recent photo is of Louis Kahn’s Salk Institute in La Jolla, California (shot in 1977). Given its significance, more people ought to know about Ezra Stoller’s estimable career, and this book will help broaden his reputation. After all, it isn’t easy to produce a photograph of an almost universally familiar building that still looks fresh thirty, forty, and even fifty years after the shutter snapped.