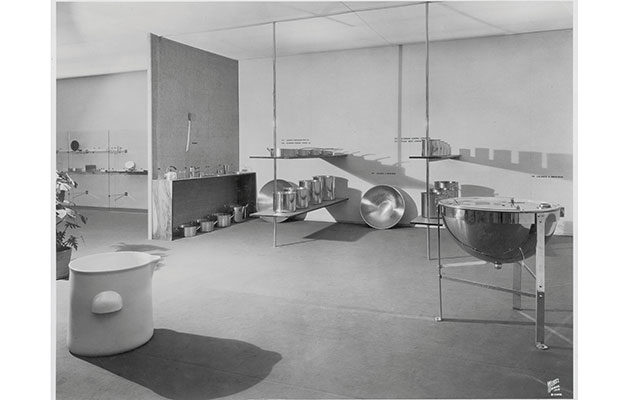

Installation view of Machine Art at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1934. | © THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART/LICENSED BY SCALA/ART RESOURCE, NY

Installation view of Machine Art at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1934. | © THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART/LICENSED BY SCALA/ART RESOURCE, NY

Feature

The Silent Partner

LONG BEFORE HE ACTUALLY COMPLETED his architecture degree in 1943, Philip Johnson was the first curator of architecture and design at the Museum of Modern Art. His early important exhibitions there— Modern Architecture: International Exhibition in 1932 and Machine Art in 1934—typified his lifelong practice of achieving success through collaborations with other talented individuals. He worked with Henry-Russell Hitchcock and Alfred H. Barr Jr. on Modern Architecture and with Jan Ruhtenberg on Machine Art. Although the Hitchcock-Johnson connection is well known, little information has been available until recently about Johnson’s partnership with Ruhtenberg, even though the success of Machine Art was due in large part to it. Not only has Ruhtenberg’s important role in the exhibition been overlooked, so has his later architecture.

Born in Riga, Latvia, Ruhtenberg attended the University of Leipzig and worked for a furniture manufacturer until 1928, when, at age thirty-two, he received a full scholarship to study architecture at the Berliner Technische Hochschule and moved to Berlin with his wife and three children. He met Johnson the following year, and a personal relationship between the two began to develop. Johnson visited Europe frequently, for months at a time, and he and Ruhtenberg traveled together, visiting the Bauhaus in 1930, and shared an apartment, designed by Ruhtenberg, at 22 Achenbachstrasse in Berlin. Johnson wrote to his mother— on new letterhead designed by Ruhtenberg—that it was his “permanent address in Europe from now on,” though in the end they probably only shared it in 1930, and perhaps in the summer of 1931.

As his relationship with Ruhtenberg deepened so did Johnson’s friendship with Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. On September 17, 1930, Johnson wrote about Mies van der Rohe to the Dutch architect J. J. P. Oud: “It was curious how I got to know him so well. You know how impersonal and impassive he is. After seeing some of the rooms that he had decorated here in Berlin, I got the idea of getting him to do my room in New York for me. I went to call on him with my best friend, a German, Jan Ruhtenberg, who is beginning to study architecture. Mies was most polite and distant, but we were lucky to be going to Dessau the same day he was going, so we took him with us in the car and then he opened up and talked all the way. . . . By the time we were back in Berlin he had agreed to take my friend Jan as the first voluntary assistant that he has ever had.”

Ruhtenberg was working in Mies van der Rohe’s office when Johnson commissioned the design of his New York apartment in July 1930, and he worked on the project with the architect’s partner Lilly Reich. Johnson deposited funds in Ruhtenberg’s Berlin bank account so that he could pay German manufacturers for the furnishings for the apartment as well as Mies van der Rohe’s fees on his behalf.

Though Johnson had no formal training in design at the time, he and Ruhtenberg had sketched ideas for Johnson’s apartment during their travels in Europe. They also collaborated on designs for Johnson’s mother’s house in Pinehurst, North Carolina. Ruhtenberg would soon take on more major projects, both in his own right—designing a “house for a childless couple” in collaboration with Carl Otto for the German Building Exhibition in 1931, for example—and in partnership with Johnson.

In July 1933 Johnson wrote to Barr, “I have Eddie’s [Edward M. M. Warburg] apartment to do and Dr. Morrissey’s office in addition so I cabled Jan to come right over.” Ruhtenberg, who had divorced his wife and moved to Sweden two years earlier, arrived in New York on November 4, 1933. According to the manifest of the S.S. Frederik VIII he was a thirty-seven-year-old architect on his first visit to the United States and intended to stay with his “Friend: Philip Johnson/Museum of Modern Art.”

While a photograph of the Achenbachstrasse apartment was included in Johnson and Hitchcock’s 1932 book The International Style, and Ruhtenberg is thanked there for “reading and criticizing” the text, it was in the Machine Art exhibition that his influence can most clearly be seen. Reviewing the show, Henry McBride wrote in the New York Sun on March 10, 1934, that Johnson had “such a genius for grouping things together and finding just the right background and the right light.” But letters and other documents and photographs unearthed much later reveal that much of the credit should be shared with Ruhtenberg—far beyond his “assistance in designing the installation” noted in the exhibition catalogue.

Compared to Johnson’s banal installations for Modern Architecture in 1932 and Objects: 1900 and Today in 1933, Machine Art was remarkable for its visual impact. The more than six hundred industrial objects included took up all three floors of the former Rockefeller town house that served as the museum building at the time. Influenced by German trade shows with innovative designs by Mies van der Rohe and Reich, Johnson and Ruhtenberg grouped industrial designs (WearEver aluminum cooking utensils and Crusader hotel saucepans by Lalance and Grosjean) like sculpture in simple settings, emphasizing the aesthetic rather than the functional through dramatic lighting. Muslin concealed architectural details such as cornices and fixtures; black velvet table coverings provided drama in the third-floor “jewel room” where laboratory glass was shown.

The catalogue included equally dramatic photography by the then little-known Ruth Bernhard, also a German immigrant. Although the publication gives no design credit other than the cover by Josef Albers, Bernhard later recalled the circumstances: “In the early 1930s I was living on the corner of 34th Street and Lexington Avenue. . . . Jan von Ruhtenberg, who lived upstairs, was in charge of the design of the catalogue for the 1934 Machine Art exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. He probably had never seen a photograph of mine, but, perhaps out of convenience, he suggested that if I’d like to do the illustrations, he’d start sending things over . . . . I arranged jars and glass bottles. I just loved the way they looked. I saw beauty in the light on objects.” Though Bernhard went on to become a famous photographer of female nudes, she regarded this commission as her first big break.

The Johnson-Ruhtenberg working partnership lasted until Johnson left MoMA at the end of 1934 to pursue extreme right wing politics. Ruhtenberg remained in New York, working as an architect and teaching at Columbia University from 1934 to 1936 before moving to Colorado in 1940. Although Ruhtenberg remained comparatively unknown throughout his life, he was among the German émigrés instrumental in the spread of Bauhaus ideas and modern European architecture in North America. In 2013 his grandson Vessel Ruhtenberg organized an exhibition for the Indianapolis Museum of Contemporary Art, Jan Ruhtenberg: Come Here Architekt, an important first step in the process of making this talented architect better known.