Installation view of works by Brigitte Mahlknecht (left), Judith Saupper (center), William Cordova (right). Image Courtesy ACFNY/Luca Mercedes.

Installation view of works by Brigitte Mahlknecht (left), Judith Saupper (center), William Cordova (right). Image Courtesy ACFNY/Luca Mercedes.

Exhibition

The Projective Drawing at the Austrian Cultural Forum

Ever since the avant-garde architect Raimund Abraham’s design for the Austrian Cultural Forum in New York City was completed in 2002, the slender, tapering glass and aluminum tower has been compared to many things including a blade, a guillotine, a light-filled totemic figure, an intergalactic guard tower, and a tiered mountainside. The evocative quality of the building, both from the outside and within, makes it the perfect site for curator Brett Littman’s new show, The Projective Drawing, which will be on view at 11 East 52nd Street until May 13. In many ways, Littman has arranged the show to work in dialogue with architectural historian Robin Evans’s seminal book, The Projective Cast, which argues that we need to expand the ways in which we describe architecture, taking into account the multiple dimensions of individual perception. The exhibition is about how we explain the world, especially the world of architecture, through drawing and also the ways in which drawing is inherently incomplete, only partially able to convey the complexities of experience on its own. The show presents work by ten artists based in Austria and New York, as well as one who lives in the Peruvian Amazon, all working in the interface between drawing and design. Sometimes the work takes the form of hypothetical architecture or hypothetical landscape but in other cases it focuses is on pattern, sound, perception, or even pathology as in the case of Sara Flores whose hand-drawn asymmetric motifs are intended to prompt healing for those who share her art.

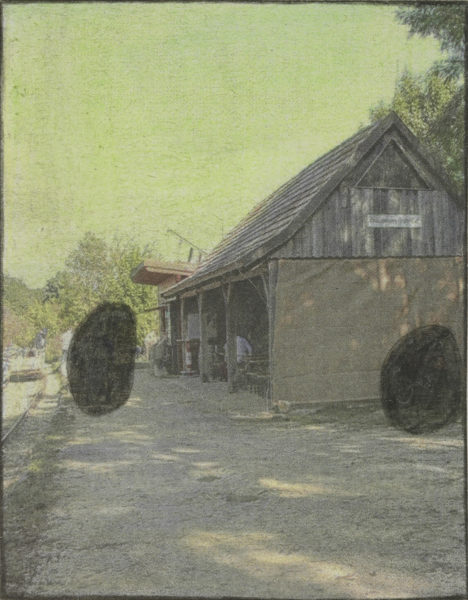

Untitled by Leopold Strobl, 2014-033, 2014. Pencil and color pencil on paper. All works are courtesy of the artist and Galerie Gugging.

Leopold Strobl’s tiny, lyrical, and enigmatic drawings (many are just about the size of playing cards), provide a good sense of the challenges that concern this group of artists. Strobl has worked for many decades, systematically rendering buildings, roads, or seascapes with pencil and colored pencil on top of newsprint clippings mounted on paper. His compositions are reminiscent of the work of German Expressionists like Erich Heckel, with simple massed volumes and confident, thick rolling lines. But it’s Strobl’s habit to begin each picture with a darkened area or negative space (sometimes more than one) and these organic shapes or ‘voids’ may be integrated into the narrative of his drawings while sometimes they completely interrupt the artistic logic. In certain cases, they can be interpreted as ambiguous shadows of trees or cutouts of vegetation surrounding a body of water. At other times, they serve as objects in surreal narratives—a lumpen looking dark cloud drifting in a clear sky, for instance. When they’re most maddening, the voids act like eye floaters, blocking out part of a scene and calling attention to the difficulty or even impossibility of adequately understanding physical space through two-dimensional pictures.

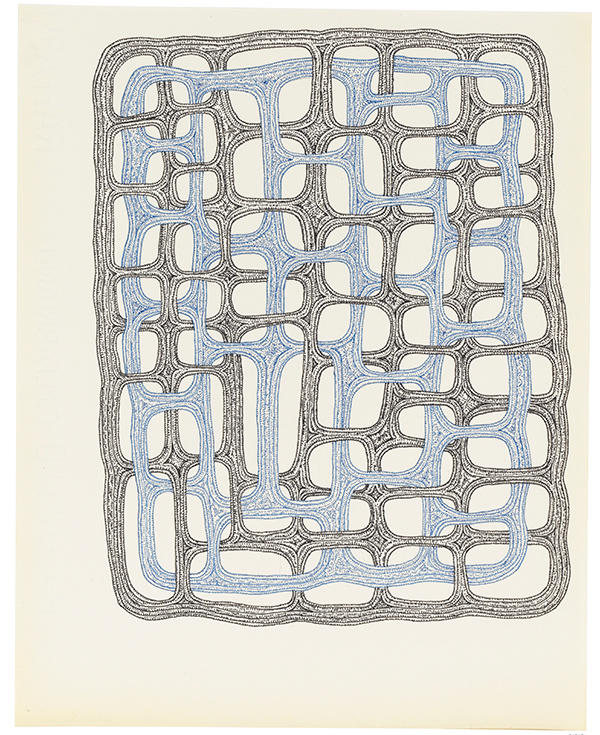

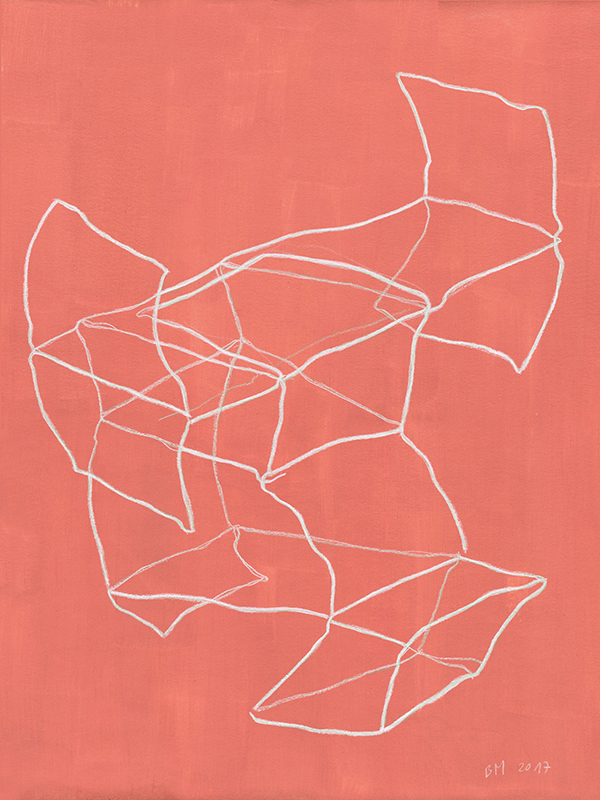

Fast Architektur by Brigitte Mahlknecht, 2017, Wax crayon on primed paper. Courtesy of the artist.

In Brigitte Mahlknecht’s series Fast Architektur, the artist’s hastily drawn sets of stacked boxes might also be read as hurried depictions of architectural structures drawn in what seem to be chalk lines but are actually wax crayon lines. Scrutinize the sketches carefully and they’ll set off a series of unresolvable questions in your mind: What is the base point? How is this construction supported? What’s inside? What’s outside? What’s folded in? What’s folded out? Is there a way out or a way in? Is this the depiction of a container or a shelter? Are the walls solid or can they be penetrated? Are these irregular structural lines or are they squiggles? Is the whole thing about to collapse? Again, the ambiguities raise questions about drawing and its insufficiencies, particularly as we attempt to visualize the three-dimensional space of architecture.

The Great Noise by Judith Saupper, 2014. Paper sculpture, six lengths of paper with 475 collaged ink drawings. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Straihammer und Seidenschwann, Vienna; image courtesy of Bildrecht Wien 2018, Katja Bode.

Finally, Judith Saupper’s installation The Great Noise, almost filling the entire lower level of the Austrian Cultural Form, exemplifies the core issues of the show. Saupper has covered her seven-meter-long paper with delineated hills and valleys as well as a collage of hundreds of flat and cartoonish ink drawings of Austrian-style buildings and houses selected from photos and images. If the paper were to be laid out, it would look like a whimsical topographic map, but the artist has arranged her paper to bunch-up, rise, arch-over like waves, and spread out like curtains. In this way, she’s literally projected three-dimensionality off of a two-dimensional surface. The work shows the expressive potential of projective drawing and it demonstrates the exhilaration that occurs when a flat surface is given the freedom to roll-up or fall, crease or bend while playing in space which, of course, is the first step of imagining architecture. This is a

provocative work of art in a provocative exhibition which is ultimately unsettling, challenging, and conceptually daring.