Feature

The House of Tomorrow

LONG AFTER CHICAGO’S 1933–1934 CENTURY of Progress exposition you could still come across medallions, postcards, and bric-a-brac from the fair bearing the handsome art deco logo of a tilting planet Saturn with its outer rings sweeping up and out into the farther solar system. The exposition was intended to be about the times ahead— motion and flight represented by an Italian squadron of twenty-four seaplanes that flew from Rome to Chicago, landing spectacularly on Lake Michigan close to the fairgrounds. The House of Tomorrow, designed by Chicago architect George Fred Keck, was one of the most popular exhibits. Visitors paid an extra ten cents to take a tour of the futuristic house, a dodecagonal structure with glass curtain walls on the upper two floors and a ground-level indoor automobile garage for the Pierce-Arrow Silver Arrow parked outside, as well as a hangar for a replica of Lindbergh’s Spirit of St. Louis. As his younger brother and eventual partner, William Keck, said, George Fred’s idea was “to go as far out into left field as he possibly could with a design, and then bring them back to earth enough to show what could be done.”

It’s almost impossible to imagine how radical the flat-roofed, twelve-sided house appeared in its day, with virtually floor-to-ceiling tinted storefront glass windows and phenolic-board cladding, which was replaced with standing-seam copper for the second season. Even when you look at the fair pictures today, the house festooned by open decks with metal pipe railings seems like a cross between a Victorian summer pavilion and a colossal aquarium. There is something both innocent and charming about its audacity. Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion House was certainly one of the influences, but the Kecks were born and raised in Watertown, Wisconsin, where the five-story Octagon House, built before the Civil War, had inspired them. Standing atop a hill overlooking the Rock River, the stately old building was a testament to ingenuity. Without electricity, the house’s designer, a pioneer lawyer named James Richards, had managed to create a ventilation system in the living quarters and to install running water in the kitchen and up to the second floor. These were the sorts of things that interested the Kecks, and not quite eighty years after the Octagon House had been built, George Fred translated what he had seen as a boy into an even more modern structure with the newest materials and technologies.

This Kaufmann & Fabry Co. photograph, taken during construction in 1933, shows the simple “spoke-and-hub” steel substructure of the House of Tomorrow. When the building was completed and the glass walls installed, the central stack was left exposed as part of the “streamlined” design. Courtesy Wisconsin Historical Society

Aside from the automobile garage and airplane hangar, the ground level of the House of Tomorrow accommodated a utility room, a gentlemen’s lounge (turned into a bar during the fair’s second season), and a workshop with machine lathes in case the automobile or airplane needed servicing. Like the Octagon House, which had a central stairway, the House of Tomorrow was built around a central stair, but in this case, the stairway spirals around an exposed cylindrical utility chase. The tube brings up conditioned air and electric wiring, with a ring of steel I-beams radiating out from it like wagon-wheel spokes. The I-beams cantilever the structure so that weight doesn’t bear down on the glass walls. By changing the Octagon House’s eight sides to twelve, Keck was able to establish partitions for modestly sized, wedge-shaped rooms that flow into one another—from the living-dining area to the kitchen, children’s bedroom, bath, and master bedroom. The top floor, designed as a “conservatory,” was used as an observatory during the fair from which visitors could look out over the grounds.

Photograph of the House of Tomorrow taken by Kaufmann-Fabry in 1934, after the house was sheathed with polished sheet copper, replacing the original phenolic board that wrapped around the bottom floor and between glass panels of the upper stories. Some 750,000 fairgoers visited the House of Tomorrow during the first season and half a million came the second year. They paid an extra ten cents to visit, for unlike the other fair houses, the House of Tomorrow did not have an industrial sponsor. Courtesy Wisconsin Historical Society

The house was a laboratory for many of the principles the Kecks would refine later. It was publicized as “a housekeeper’s paradise, since there were no corners for dirt to collect [in].” The Kecks were using glass in new ways and still learning how to get a balance of light and heat into all the rooms to share the benefits. They covered many of the interior walls with pigmented Carrara structural glass manufactured by the Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company in order to achieve reflectivity, a passive form of indoor light when the sun was shining. On cold days, the rooms were heated with forced warm air that was vented into the rooms, but the Keck office was also discovering the bonus effect of passive solar heating. While the house was still under construction in the early spring of 1933—when, as William Keck said, “It was damn cold outside”— they noticed that workmen were only in shirt-sleeves inside the glass walls. This was the greenhouse effect, and it was something they exploited in most of their later projects in order to diminish the cost of heating. Air conditioning produced different challenges. They experimented with a now-obsolete water cooling system to bring down the temperature on hot summer days, but the panes of nine-by-twelve-foot glass installed in the house created a thermal barrier, particularly in the west-facing bedroom. The lessons the Kecks learned led to the development of Thermopane.

Intended as an optimistic predictor of future residential architecture, the house was equipped with an airplane and hangar, as well as an automobile and garage on the ground floor, as captured in this 1933 photograph by Hedrich- Blessing. © Chicago History Museum

George Fred Keck had been educated in architectural engineering and he was acutely attentive to the physical properties and uses of his materials. He installed protective steel turnbuckles to keep the house from pivoting with the wind coming up off the lake; otherwise, the giant sheets of glass would have fractured and broken. The many technological innovations he introduced drew in the crowds. During the first season the house’s all-electric kitchen included General Electric’s first dishwasher; in the second season gas was introduced, allowing the installation of an “iceless refrigerator.” The stairwell was illuminated with cove lighting, and all the lighting was connected to dimmer switches. Remote-controlled radio was wired into all the rooms. Remarkably, the Silver Arrow was parked outside a garage with an electronically powered overhead door that opened, according to Popular Mechanics, “at the push of a button.”

Like all the buildings constructed for the fair, the House of Tomorrow was built slab-on-grade with fireproof factory-made materials such as drywall bolted into place at the site. From start to finish, it took a little more than two months to construct and was intended to be used only during the two seasons of the Century of Progress. At the end of the second season, a speculator named Robert Bartlett had the idea to buy some of the houses built for the exposition and transport them by truck and barge across the lake to Beverly Shores in Indiana, where he was developing a tract of land. Bartlett paid the Kecks five hundred dollars and was responsible for removing the structure from the fairgrounds. Once it arrived at its new location on the top of a dune, he had the original windows removed and reduced the size of the frames, making them operate like conventional casement windows. He made a few other changes, especially to the ground floor, which no longer needed an airplane hangar. Eventually, Bartlett placed the house on the market and sold it in 1938. Like the other houses from the fair, the House of Tomorrow remained privately owned until the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore was created and the historic houses were purchased by the National Park Service. In 1970 the owner of the House of Tomorrow was granted a reservation for use with the right to live in the building until the late 1990s, after which it was leased to Indiana Landmarks. Since 2002 it has been empty and has badly deteriorated.

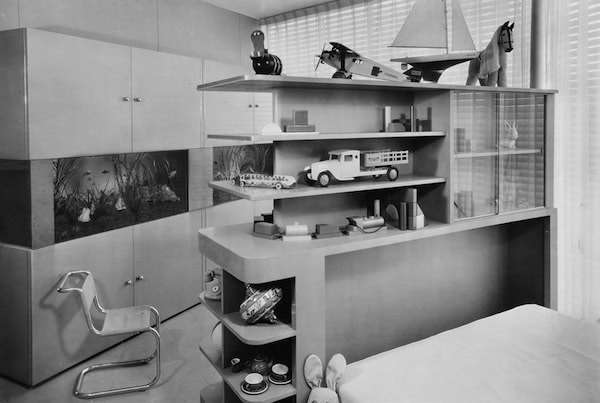

The turquoise-colored children’s bedroom delighted visitors with its large storage cabinet fitted with an aquarium for tropical fish. In the middle of the room, an ingenious cabinet was fitted with toys, Montessori-style materials, a tea set, and a telephone. Pullman beds could be pulled down from it when it was time to sleep or folded up to make space for play. Irene Kay Hyman was the decorator. The 1933 photograph is by Kaufmann & Fabry Co. Courtesy Wisconsin Historical Society

The exterior has rusted, and the drywall has disintegrated so you can barely identify original paint colors. Much of the Carrara glass simply disappeared from the walls. Clad in protective wrapping, it looks like a gigantic stack of hatboxes mysteriously deposited on Lake Michigan’s shore.

In October 2016 the house was designated a National Treasure by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, which is working in partnership with Indiana Landmarks and the National Park Service to preserve and restore it from foundation to roof. Indiana Landmarks has begun a fundraising campaign for the restoration, and when the work is completed the plan is to lease the house for terms of two to three years at a time. Todd Zeiger, director of Indiana Landmarks’ northern regional office, describes the undertaking with enthusiasm: “The views are going to be spectacular, as you can imagine, with the glass all the way around.”

The kitchen, seen here in a 1933 photograph, was designed with the most up-to-date features, including steel and glass cabinets finished in sand-colored enamel, a Monel metal sink and Monel countertops, a General Electric dishwasher, a General Electric refrigerator, and a Sunbeam Mixmaster. © Condé Nast

Zeiger plans to keep the house open as they do the rehab, and then open it again for tours a few times a year. The complete overhaul will stabilize the structure and save what’s possible (such as kitchen cabinets), restore what’s missing (such as finding a facsimile of the Carrara glass), and hopefully track down some of the original furniture used during the fair. The goal, Zeiger says, is to balance the House of Tomorrow of 1933 and 1934 with a new House of Tomorrow of 2017–2018–2019, remaining true to what Keck was trying to do aesthetically by respecting his design and the overall feel of the house but also introducing new innovations and the latest technology. The intention is to make the house as green as possible, installing geothermal heating with a small, high velocity forced-air system, radiant heated floors, and a solar roof. New landscaping will blend the manicured front lawn that one sees in postcards of the fair with a more naturalistic and grassy look appropriate to its current setting in the dunes.

Hedrich-Blessing’s 1933 photograph shows the living- dining area. The Kecks conceived the room as a transitional space, and the furniture was designed to be light and portable, useful for different purposes. In order to protect against heat during hot summer days, the Kecks installed silver-painted Venetian blinds, and a curtain that could be pulled across for privacy. The interior walls were covered with black and gray Carrara plate glass and the floor was finished with end-grain black walnut. The firm of Tapp, DeWilde and Wallace made the wood furniture and W. H. Howell Company manufactured the metal tubular furniture. © Chicago History Museum

“Keck,” Zeiger explains, “reinvented the octagon to make this house. He started looking at the octagon and kind of blew it up.” The hope is to stretch the house once again, making it a platform for exploring the future. Brian Berg, a spokesperson for Indiana Landmarks, adds, “We can talk about Wrigley Field, right? It’s been adapted, improved, restored, it has its original character, and it’s sustainable for the future. So, a family can live here, pay rent, it can be kept up. It’s not a museum.” The Kecks, who took architectural design “as far out into left field” as possible, would have approved of the Chicago baseball analogy.

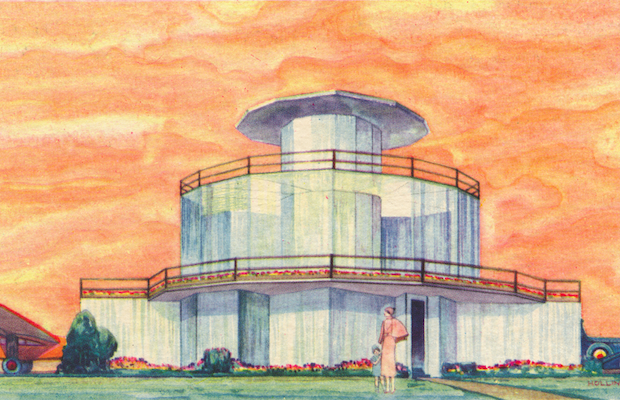

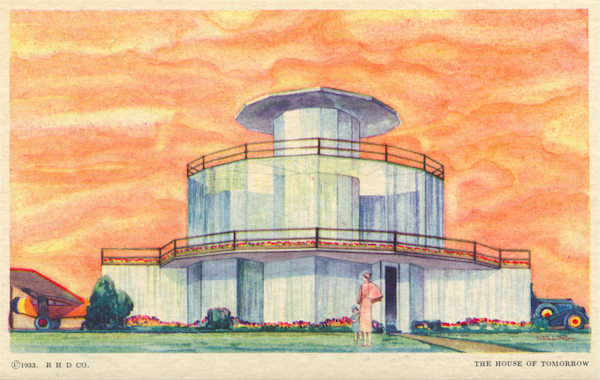

Postcard showing an artist’s rendering of the House of Tomorrow at the Century of Progress exposition in Chicago, printed by the Reuben H. Donnelley Corporation in 1933. The coloration of the yellowish-orange sky is a reminder that the fair was supposed to suggest a rainbow-colored city, in contrast to the 1893 Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition, famously nicknamed the White City.