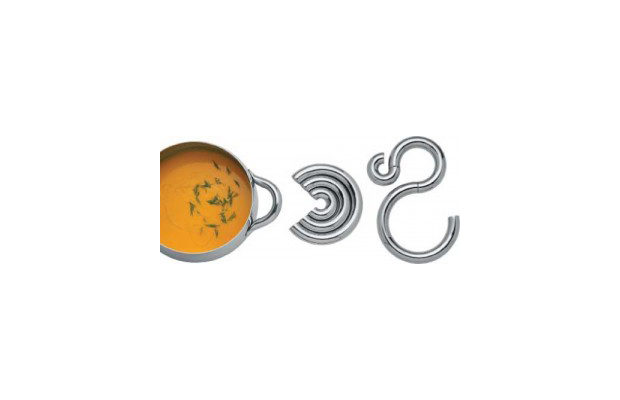

The Try it trivet designed by Dror Benshetrit in 2009 is composed of three stainless steel arcs. Each piece can be considered a trivet in its own right; when assembled together they create a stable suppor for multiple uses.

The Try it trivet designed by Dror Benshetrit in 2009 is composed of three stainless steel arcs. Each piece can be considered a trivet in its own right; when assembled together they create a stable suppor for multiple uses.

Feature

The Dream Factory of Alessi

PROMISE AND POLISH IN SILVER AND CHROME (AND PLASTIC AND PORCELAIN)

In 1918 four Polish immigrants opened a studio on Sunset Boulevardin Hollywood. That studio, Warner Brothers, soon became one of the best of the so-called Dream Factories, most admired for its gritty Depression-era movies.

Around the same time, Giovanni Alessi, an Italian metalworker who excelled at making brass knobs, opened a studio of his own, in a valley near the Swiss border. Though this studio made small objects for the home—metal coffee- and teapots, trays, flask holders—it shared something with Warner Brothers: Alessi was rooted in handsome practicality, not lavishness.

Today, the Hollywood Dream Factories are long gone, but Alessi is thriving, with one eye still focused on function and the other on art and invention. Some of the greatest designers and architects of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, including EttoreSottsass, AchilleCastiglioni, Aldo Rossi, Michael Graves, Philippe Starck, Norman Foster, and Jasper Morrison have worked with the company. The president, Alberto Alessi, grandson of the founder, calls it “the dream factory.”

Since 1921 Alessi has operated from the same northern Italian valley within striking distance of the Alps, and it doesn’t outsource everything to China: virtually everything made of cold-pressed metal or of wood is still manufactured in Italy. “Everyone there is extremely loyal,” says the gifted Israeli designer DrorBenshetrit, who is creating a collection for the company. “For many of the people I work with at Alessi, it’s their first job, and will probably be their last. And they maintain a lot of their local craft, even though it costs more.”

These days you can indulge in an Alessi bathroom, equipped not only with Alessi fixtures but with an Alessi bathtub plug, toothbrush holder, toothpick holder, toilet brush, soap dish, and laundry basket. Not to mention a scale, which you might want to avoid after cooking dinner in an Alessi-designed kitchen, deploying Alessi pots, pans, dishes, glasses, and cutlery. The company has produced (and this is by no means a complete list) egg cookers, honey pots, spice jars, nutcrackers, timers, clocks, watches, graters, bottle openers, compact-disc racks, corkscrews, candlesticks, calculators, colanders, lemon squeezers, trolleys, garden tools, vases, cruet sets, toast racks, telephones, radios, desk organizers, wastepaper baskets, tables, figurines, frames, mirrors, and (dare we mention them in the United States?) ashtrays. In some corners of the world, you can even drive a Fiat Panda Alessi. “I believe that all industrial products would strongly benefit from a design-excellence approach,” Alberto Alessi says.

Carlo Alessi—Alberto’s father—was an industrial designer who shepherded the company through the Depression and World War II, and produced the sleekly stout Bombé tea and coffee sets that his son has called the “archetype of early Italian design”—a harbinger of what was to come. “Right after the 1940s,” Alberto Alessi says, “the company changed from pure craftsmanship to industry, from lathe-spinning to presses.” It was not until 1988 that the company expanded its manufacturing base to wood, and in the next five years added plastic, ceramics, and glass. “We are metalists by roots,” Alessi says.

The quantum leap came in 1979 when Alessandro Mendini proposed having several architects, including Robert Venturi and Richard Meier, design classic silver tea and coffee services. Produced in limited editions, they were elegant, inspired—and witty. Something was changing. Philippe Starck may have said it best: “Alessi sells joy.” Who could not respond happily, for instance, to Michael Graves’s now-classic tea kettle with a bird at the spout or his cheese tray with a mouse for a handle? Alberto Alessi agrees. “I trace playfulness in our design history in Michael’s works for us,” he says, “and in a different way also in masters like Castiglioniand Mendini.”

Though the company’s association with superb designers is long, Alberto Alessi has brought in the greatest number and variety (none is a resident employee, however). In 1990 Alessi began working with unestablished designers, including students, which has revivified the house; the firm has also established workshops, including one at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan. Alberto Alessi thinks of his job, in part, as “managing a stable of racehorses. There are approximately two hundred and I try to take care of every one of them in the best way. They well know how I rely on them.”

Designers clearly relish not only the freedom Alessi gives them, but the technical risks the company is willing to take. Says the Milan-based Miriam Mirri, whose items for Alessi include the delicious porcelain and stainless steel Babette coffee cup: “They have the courage to follow my intentions or to suggest new solutions, sometimes based only on trust.” Bonnie Mackay, the former director of merchandising, creative, and marketing for MoMA Retail, has worked closely with Alessi. “They’re open to anything, which a lot of companies aren’t,” she says. “That’s why we love them. Alessi does a lot of investigation. They mix things, like plastic with stainless steel. That needs two different molds, but they’re willing to take the step. They push it farther than other people do. ”

Then there is the instantly identifiable Alessi look. Like music, it is difficult to describe. “They are unbelievably focused on their product,” DrorBenshetrit says, “to make sure it has the Alessi DNA and integrity. They keep it solid. You have to; otherwise you dilute your image.” He still marvels at “how many hands one single product, even a little oil cruet, moves through.” Bonnie Mackay frequently observes customers’ reactions to Alessi and may come as close as anyone to identifying our response to “the look.” It’s not just the quality of the pieces, she says, “it’s the aha! factor. When you see something of Alessi you think, ‘I never knew you could do this.’”