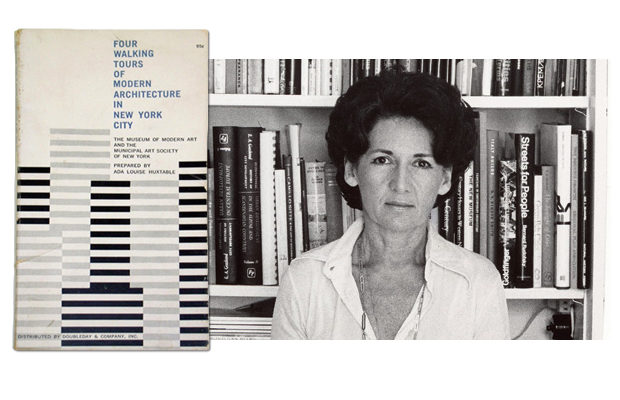

Cover of Four Walking Tours of Modern Architecture in New York City prepared by Ada Louise Huxtable (Museum of Modern Art and the Municipal Art Society, 1961). | Ada Louise Huxtable in a photograph taken by her husband, L. Garth Huxtable, 1970s.

Cover of Four Walking Tours of Modern Architecture in New York City prepared by Ada Louise Huxtable (Museum of Modern Art and the Municipal Art Society, 1961). | Ada Louise Huxtable in a photograph taken by her husband, L. Garth Huxtable, 1970s.

Feature

Streetwise

A rare copy of the critic Ada Louise Huxtable’s Walking Tours underscores her firm belief of architecture as social art

“Now to answer the question I am most frequently (do I sense, hopefully?) asked: Do I think I was ever ‘wrong?’ Sorry to disappoint, but my opinions have not really changed: I called the buildings as I saw them, and I feel pretty much the same way now. My judgments have all been made in the immediate context of their time, measured against some pretty timeless standards—something hindsight, with its re-writing of history, often prefers to ignore. Simply put, I was there; I know what happened.” Ada Louise Huxtable, 2008

IN 1961 THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART and the Municipal Art Society of New York published Four Walking Tours of Modern Architecture in New York City “prepared by Ada Louise Huxtable,” a crisp selection of alert observations and distilled history slipped into an elegant billfold-size book. Focused primarily on the postwar transformation of midtown Manhattan, Huxtable (née Landman) is, of course, an erudite native guide: born in 1921, raised on Central Park West in the gracious St. Urban (Robert T. Lyons, 1906) as recalled in her memorable 1975 essay “Growing Up in a Beaux Arts World,” she came of age during the World of Tomorrow. After graduating from Hunter College, she studied architectural history and found a sales job and her future husband at Bloomingdale’s. In a 1941 business collaboration with MoMA’s Organic Design in Home Furnishings exhibition and design competition, twelve American department stores—including Bloomingdale’s—had been contracted to sell the prize-winning furniture. The man Landman would marry, an industrial designer named L. Garth Huxtable, was perusing the Eames and Saarinen molded plywood chairs when they met.

In 1963 Ada Louise Huxtable, who’d spent a Fulbright year in Italy and served as an assistant curator at MoMA, became the architecture critic for the New York Times and the first full-time architecture critic at any American newspaper. Over the next fifty years her ardent, self-assured prose was recognized by the Pulitzer Prize and the MacArthur Foundation and reached a wide readership, creating a public dialogue about the built environment and everything that can make a city a better place.

Huxtable developed Four Walking Tours, a seventy-six-page paperback with an original cover price of ninety-five cents, over a five-year period, expanding on mimeographed notes she’d produced for volunteer guides at the Municipal Art Society and incorporating maps, updated information, and a few small blackandwhite photographs. Although the sites featured in the guide reveal her frank appreciation for pioneering midcentury innovation and design (has anyone else composed such succinct but marvelous odes to a skyscraper’s glittering skin and the miraculous qualities of glass curtain walls?), this little book is not all modern love. In “Tour No. 1: Park Avenue (43rd to 59th),” she is quick to reprimand the Pan Am Building (Emery Roth & Sons; Pietro Belluschi and Walter GropiusTAC, consultants, 1960–1963), a behemoth tower then still under construction that aggressively straddled Grand Central Terminal—the splendid Gilded Age focal point of Park Avenue—and over whelmed the neighborhood. “It [the Pan Am Building] will also add an extraordinary burden to existing pedestrian and transportation facilities,” she sharply warns. “And in these aspects its antisocial character directly contradicts the teachings of Walter Gropius, who has collaborated in its design.”

The exterior of the Rockefeller Guest House, designed by Philip Johnson, New York, 1948–1950, in a photograph by Robert Damora.

As always, Huxtable recognizes architecture as a genuinely social art and considers everything from the skyline down to the crowded sidewalks. Appraising the 1950s building boom of high-rise office towers along stately Park Avenue, she admires the rational, austere beauty of Lever House (Gordon Bunshaft and Natalie de Blois of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, 1950–1952) and the Seagram Building (Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Philip C. Johnson; Kahn & Jacobs Associates, 1956–1958), and regrets the characterless and shoddy commercial imitations they spawned.

Huxtable, who died in 2013 at the age of ninety-one, admitted she’d never envisioned an era she dubbed “Skyscrapers Gone Wild” and the twenty-firstcentury race to “claim the slippery title of world’s highest and most ostentatiously vulgar building.” Her walking tours traverse the canyon-like streets of midtown—north from Forty-Second to Sixty-Sixth Street and east from Fifth to Second Avenue—an area now punctuated by wild vertiginous towers: to the west, One57, the “Billionaire Building” more than a thousand feet tall and notorious for its perilous crane collapse during Hurricane Sandy; and to the east, 432 Park Avenue, billed as “the tallest residential tower in the Western Hempishere,” a monolith by architect Rafael Viñoly, supposedly modeled on a 1905 trash can designed by Josef Hoffmann. Looking upward at these buildings is dizzying; they are like a nihilistic sci-fi vision of some inhuman metropolis. Huxtable’s fifty-five-year-old guidebook, however, offers a welcome alternative, a sort of sophisticated treasure map that can lead you to indomitable monuments and forgotten riches, while also disclosing plundered sites and ruthless destruction.

One57 on Fifty-Seventh Street was designed by Christian de Portzamparc and completed in 2014.

I’ve followed Huxtable’s walking tours into the sheltering terrazzo-paved plazas of corporate headquarters and down the avenues in search of extinct businesses—Bonnier’s Inc., purveyors of understated Scandinavian design; the Olivetti showroom, a luxe outpost for the visionary Italian manufacturer, publisher, design entrepreneur, and social reformer; and the Frank Lloyd Wright–designed automobile showroom, where new sedans were displayed on a spiraling ramp. Traversing midtown Manhattan, you experience a Rockefeller world: from Rockefeller Center, a city within a city, to the Museum of Modern Art (founded in 1929 by Abby Aldrich Rockefeller and two friends, all progressive and influential patrons of the arts). On Fifty-Fourth Street, directly behind MoMA, Huxtable points out the handsome Rockefeller Apartments (Harrison & Fouilhoux, 1936) featuring an undulating facade, floor-to-ceiling windows, and a central garden court. Further east at 242 East Fifty-Second there’s a serene little brick, glass, and steel town house, a former stable remodeled in 1950 by Philip Johnson for Blanchette Rockefeller as a guest house. Huxtable also commends the bright and spacious Park Avenue branch of Chase Manhattan Bank (Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, 1959); in 1959 Chase president David Rockefeller founded the bank’s ambitious art program, commissioning a Sam Francis mural for the Park Avenue building’s informal board room on the fourth floor and installing a twenty-foot Alexander Calder mobile on the second floor.

Unexpected art in public and semi-public spaces—the Calder mobile is visible from the street, for example—is among the many site-specific treasures to be discovered via this book. In the lobby of the Tishman Building (Carson and Lundin, 1958), Isamu Noguchi designed the aluminum-banded ceiling and a waterfall sculpture dismissed by Huxtable as “less than successful.” There’s an exuberant mosaic by Hans Hofmann wrapped around the elevator bank at 711 Third Avenue (entry currently not allowed); on Fifty-Sixth Street near Fifth Avenue, you can glimpse the lobby wall of the former Corning Glass Building paneled with Josef Albers’s Two Structural Constellations—floating parallelograms, gold lines inscribed in white marble. When the Manufacturers Trust Company Building opened on Fifth Avenue and Forty-Third Street in 1954, it boasted the “largest glass panes installed in a building in this country” and Golden Arbor, a nearly six-ton sculpted metal screen by Harry Bertoia; in 2012, when the property was renovated and adapted for retail space, the spectacular Bertoia screen was restored.

Isamu Noguchi’s stainless-steel bas-relief mural News hangs over the doors of 50 Rockefeller Center, a fitting tribute to the building’s former tenant, the Associated Press.

In 1930s Manhattan, modern domestic architecture was a rarity. Huxtable’s guide includes the notable exceptions: two narrow nineteenth century town houses radically remodeled by architect homeowners (Morris Sanders, 219 East 49th Street, 1935; William Lescaze, 211 East 48th Street, 1934), and Edward Durrell Stone’s brownstone featuring a glass facade shaded by a pierced terrazzo screen (130 East 64th Street, 1957). Although residential use of glass block walls and sleek industrial finishes quickly became commonplace, these houses—along with Russel and Mary Wright’s nearby home and office, modernized in the 1940s—still convey an exhilarating originality.

My search for the Olivetti showroom (Lodovico Barbiano di Belgiojoso, Enrico Peresutti, Ernesto N. Rogers, 1954) was bewildering, haplessly teetering toward the mythological. When the showroom closed in 1970, everything—Venetian glass lamps, the Italian walnut main door, designer-sculptor Costantino Nivola’s fifteen-by-seventy-foot sculptured sand-cast wall—scattered. (When Nivola offered his displaced mural to Josep Lluís Sert, the architect incorporated it into his design for the 1973 Harvard Science Center.) A lone green marble pedestal, one of the original nine, sold last year at auction. Now, the original store front facing Fifth Avenue has been divided and the street entrances renumbered. All that remains from the past is the malachite-green marble floor that once appeared like a surrealistic sea swirling around the interior and spilling out the door. A portico-like display window contained one of the green marble pedestals—a tapered cone that appeared to have grown out of the pavement. Perched atop it was a colorful Olivetti Lettera 25 portable typewriter and passersby were encouraged to stop and type: according to a charming but apocryphal wisecrack, writer and MoMA curator Frank O’Hara stopped by while composing his Lunch Poems.

The Seagram Building on Park Avenue was designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson, and completed in 1958.

The Seagram Building, “unquestionably one of the finest structures of this century,” is really at the center of Huxtable’s guidebook. Her admiration encompasses every detail, from the generous pink granite plaza to Richard Lippold’s brass rod sculptures shimmering in the luxurious Four Seasons Restaurant. Huxtable’s deep engagement with the building was both personal and professional: with her husband, she collaborated on a 1959 design commission, creating 140 tabletop and kitchen items for the Four Seasons (the remaining pieces soon to be sold with the closing of the restaurant). Embarking on Huxtable’s walking tours, one begins to see the city as she did—vigorous, fascinating, exasperating, and invaluable. This little book is not so easy to find, but like the city portrayed within its pages, it is absolutely worth looking for.