Feature

Pure Power

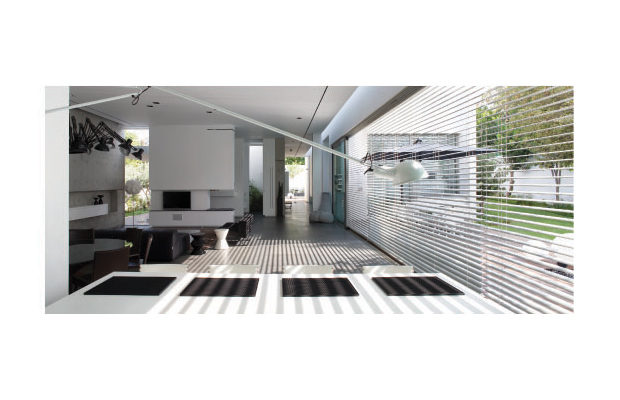

The rear facade of the house in northeastern Tel Aviv.

The defining moment in Irit Axelrod’s career as an architect arrived a few years back in Barcelona, during her first visit to the replica of the German Pavilion designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe for the international exposition held in the Catalonian city in 1929. The famed building had its effect: on cue, the scales fell from her eyes. At that moment the previously inchoate aspirations she had for her career in architecture, she says, “all started to make sense.”

A 1993 graduate of the Technion/Israeli Institute of Technology, Axelrod spent a full day at the modernist master’s temple, touring and contemplating the carefully arranged planes of travertine, onyx, marble, and glass. “My architectural life started there—the feeling I got then is what I want my clients to have today,” she says.

She was inspired by how the building’s serene procession of restrained and precisely ordered spaces created a quiet and powerful experience. “I work a lot to get that,” she says. “It’s exactly what he said: less is more. You pick the right things, but only the right things.”

Nowhere in her portfolio of work, out of her offices in Tel Aviv and San Francisco, is Mies’s influence more clearly demonstrated than in a 4,800-square-foot residence recently completed on a quarter acre in the Afeka neighborhood of northeastern Tel Aviv.

Whereas Mies employed slabs of exotic stone for the thoughtfully placed partitions in the German Pavilion, Axelrod used concrete throughout the mass of her building—though without a hint of brutalism. “Concrete is one of my favorite materials,” she says. “I like to use it in an honest way.” Still, the house is light and airy, thanks in part to the way light permeates the open interior—direct light, indirect light, filtered light—presenting the visitor with a feeling of nearly floating in space.

This free-floating sense of design is a hallmark of Axelrod’s architecture. In Tel Aviv she manipulated two-dimensional elements to create three-dimensional spaces. A minimum of wall area makes the mass of the house seem lighter and the interior more spacious. All the while, the walls frame views to the landscape, creating what Axelrod calls “visual corridors” that enliven human connections to the whole of the site. Her goal is to make a sense of place tangible. One forty-six-foot long expanse of glass can even be rolled back to create a tremendous single indoor-outdoor space.

The house emphasizes simplicity and clarity of form, but also expresses complexity and sophistication in the relationships between spaces. It’s defined by two axes, each making a strong statement on its own. One runs the entire length of the building, aligned by long skylights that guide the eye along the horizontal plane. The other is a vertical staircase opposite the entrance, defining movement from basement to living area to the master suite, which seemingly floats three feet up and five steps above the main floor. Privacy is reserved only for the master bedroom; the rest of the house is reminiscent of a loft: it’s wide open.

Although the house is only one story, it does make active use of its basement, which is visually connected to the upper floor by both the stairway and the glass walls that “float” the master bedroom block. “The kids can stay in the basement most of the day,” Axelrod says. “But the parents have constant eye connection from the main floor to the basement.”

The success of Axelrod’s architecture is achieved with something akin to sleight of hand. It’s no small-scale affair to make heavy materials feel light. “The trick was to make it large-scale, but also to make it scaled to humans too, so people feel good, rather than as if they are in an institutional setting,” she says. “It’s about how you feel when you step in—that the height and proportions feel exactly like they should.”

In essence, she’s employed a highly sensitive, near-Miesian use of restraint—of knowing precisely when and where to stop. “It has a lot of power,” she says. “Power is a good feeling. Overpowering is threatening.”

Axelrod devised what she calls “visual corridors” that run the length of the house.