Design

Morten Løbner Espersen: The Depth and Richness of Clay and Glaze

Ceramist Morten Løbner Espersen’s works in clay transcend the ordinary, as is witnessed by their presence in both museum and private collections. He terms his work an “adventure supported by fire, a process I cannot or will not fully control,” and the work that follows seems to have a magical, almost otherworldly presence. Hedge Gallery in San Francisco has an exhibition of his work, Vertigo, on view until June 22. This summer he will make his debut at Design Miami in Basel with Jason Jacques, the New York gallery that first represented him in America. Next year the Belgian design gallery Pierre Marie Giraud, will mount a solo exhibition of Espersen’s work. MODERN Magazine spoke with Espersen about his craft.

When and where did your love of working with clay begin?

Clay and I go way back. It is an old love story: I did my first clay vessel in kindergarten, and I still have my first unfired piece, because my grandmother kept it—along with many others. I never really stopped making ceramics as a kid, nor as a teenager. I spent lots of time after school in the ceramics classroom in Ålborg.

Were there specific and profound influences on your work?

In the beginning, no. I am—just like when I first began—fascinated by the numerous possibilities of shaping the soft malleable material that is clay. When I began my studies at the Design School in Copenhagen [1987–1992], most of my knowledge of ceramics was about the Greek vessels that I studied in high school. At Duperré, the art school I studied at in Paris [1989–1990], I had brilliant lectures on world ceramic history and discovered the vast traditions in museum collections, making me profoundly aware of regional cultural differences and qualities. I appreciate the richness of the Danish ceramic heritage, and am particularly fond of the work of Axel Salto, but I also like Bernard Palissy, Lucie Rie, and George Ohr. All embody sublime shapes with amazing surfaces.

I see that you studied in Denmark, France, Sweden, and Japan. Does your work bear the imprint of each of those countries and cultures (as well as their artistic traditions)?

I studied in Copenhagen for four years and for one year in Paris as an exchange student. Both schools were extremely important for my artistic development. I was trained in refining and removing all noise at the Bauhaus-inspired school in Copenhagen. In Paris I learned to welcome sumptuousness and add some more. In Japan I did not study in a classical sense, but worked twice on my own projects at different artist-in-residencies. The Japanese approach to working with clay had a huge impact on my work. In the best cases they manage to combine strict control and letting go, in a manner that seems like a synthesis of my own bipolarity—the Danish and the French. I was a visiting professor at HDK [School of Design and Crafts] in Gothenburg, Sweden, for six years. Teaching taught me a lot about understanding my own praxis, basically in asking myself the same questions I asked my students. Clearly my work bears the imprint of places I have been. I trust that every time I work in a new environment small corrections are added, as I see myself in a new light. Working away from the comfort of my own studio is very rewarding to me. I was at the Clay Studio in Philadelphia in 2008 and this summer I will work in Boston at Emmanuel College.

You work by hand and not necessarily with a wheel, is

that correct?

All my cylindrical vessels (Vacui, below and facing page bottom) are hand built, which for me is a meditative and focused method of working. It has a slow pace and reflects my hands’ hesitations and energy into the clay wall. The result is an optimal clay wall for the glazes to invade. The inner vessels in my Horror Vacui (facing page) series are wheel thrown and therefore symmetrical. Wheel throwing is also a way of meditation that requires total control and presence. I needed the precision to contrast with the opulence of the ornament, but also wanted to challenge myself to work in a new way.

In your cylindrical pots, you use a fairly straightforward and repeated shape. Is that shape a means to an end (glazes) or a metaphor?

When I work in series, it is an artistic choice stolen from ceramic history, where production of most fired clay comes in series. Repetition discards the meaning of form. However even a modest form such as a cylinder needs to be carefully shaped. The proportions must be just right in order to represent balance, inner peace, and potency. A slight alteration can pervert a harmonic shape, and make it powerless. They are vessels, but yes, you can call them metaphors, as they are devoid of function and serve as my canvases.

Your glazes are amazing. How do you derive the colors and textures. Are they fully thought through in advance or do they emerge as you are working?

All my work is a result of a previous piece. I know exactly what I want, as I have made thousands of glaze tests in order to control the results. I always fire more tests than actual work. I need to be one step ahead so I try out ideas on a smaller scale before applying a glaze to an actual work. The challenge is that only rarely can I reproduce the desired result. Occasionally it gets better but often worse. Then I keep on, I reglaze and refire according to a new plan, and in this mix of knowledge and intuition I am able to achieve the depth and richness of superimposed glazes (layer upon layer), which I cannot get in any other way. Most of the pieces in the exhibition are refired four or more times. I’d rather risk the loss of a piece than accept some mediocre surface. Approximately one in two of my works survives the firing process. I want the tactile qualities to be unparalleled by any other material, not only is it everlasting but it must be powerful.

Can you tell us the ideas behind Horror Vacui and Magic Mushrooms? They are extraordinary to look at, but they must also derive from a very deep concept and have layers of meanings.

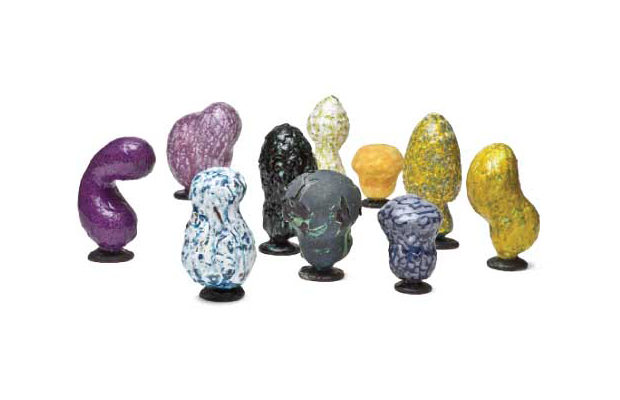

The Horror Vacui series are vessels as well. They are tributes to beauty—archetypes from ceramic art history, with a three-dimensional ornament. They are a result of a long process of research into new forms. I needed to challenge myself, and let go of what had been my primary field of work for many years, the Vacui. I spent years pursuing a desire to achieve a deeper three-dimensional surface than I had been able to create on the Vacui. My way of multi-layered glazing develops chaotically formed surfaces during firing, but I wanted to grotesque-ify it, make it sculptural. The name of the series means literally “fear of the empty space,” and was first used to describe Greek vases from 1000 bc with intricate decorations covering the surface. The Magic Mushrooms (above) are the result of another detour, the first where the vessel was not my object of choice. They are abstract forms, and form a trip that could make you high, therefore that name. The beauty of all artwork is that they have several layers of meanings, or none, depending on the eye that gazes at it.

What is coming next, after this exhibition at Hedge Gallery in San Francisco?

My next goal is to further develop the complex ornaments on the Horror Vacui series, but also to build both Magic Mushrooms and Horror Vacui in large scale at the Arabia factory in Helsinki. I have an upcoming exhibition at Galerie Pierre Marie Giraud next year in Brussels, and this June he will introduce my work at Basel for the first time.