Design

Modernism’s Modest Muse

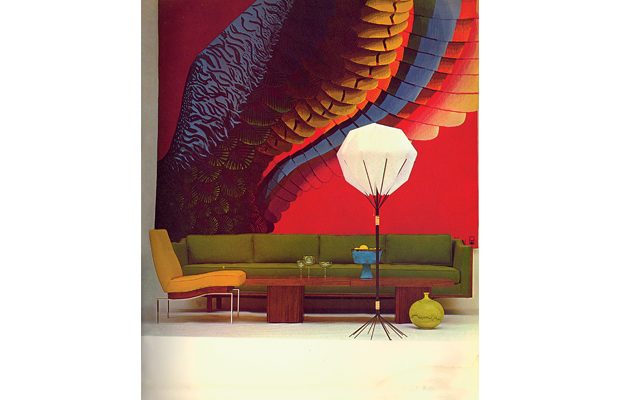

An image from the catalogue for the “California Design 9” exhibition, held in 1965, shows a tapestry by Mark Adams, a sofa by Don Donnenfield, a lounge chair by Robert Alan Martin, a coffee table by John Keal, stemware by Dorothy Thorpe, a bowl by Beatrice Wood, a bottle by James Lovera, and a lamp by Elsie Crawford.

Modernism’s Modest Muse

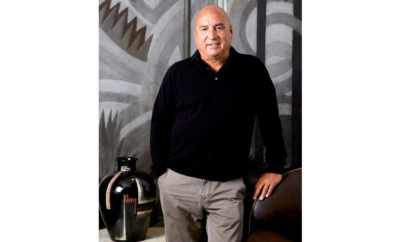

Former Pasadena Art Museum curator Eudorah Moore speaks about her role in crafting California design culture.

Southern California was famously the crucible of American modernist design and architecture in the 1950s and ’60s, but few know that one of the movement’s most ardent and effective evangelists was a woman named Eudorah Moore. Starting as a volunteer at the Pasadena Art Museum—which, after a financial crisis, was absorbed in the mid-1970s by the Norton Simon Museum—Moore went on to become the director of the institution’s wildly popular “California Design” exhibitions from 1962 until 1976, when the last of the shows was held, offsite, at the newly-opened Pacific Design Center. Described by design historian Donald Albrecht as “catalyst, muse, and talent scout,” Moore transformed what had previously been a sleepy annual event into a blockbuster juried triennial. Although Moore’s archives now belong to the Oakland Museum of Art, she remains a living repository of information and perspective on the role that California played in developing a distinctly American modernism. Sharp, generous, and still dazzled by design, Moore had a major hand in the recent California Design: The Legacy of West Coast Craft and Style (Chronicle Books) and will be featured in a forthcoming documentary film CA 45–65: Climate of Invention, which will be screened at the 2011 Los Angeles County Museum of Art show “Living in a Modern Way”—the first major exhibition to examine California mid-century modern design.

How did your involvement with “California Design” begin?

The show was started in 1954, but I didn’t get involved until the early 1960s. I was working practically full-time as a volunteer for the Pasadena Art Museum and eventually became president of the board. I just adored the museum, which was a really first-class contemporary museum, and of course cared a lot about how it was going to survive. I felt that design was a very major thing, so a friend and I talked to the director about taking over the show. Happily, he said yes.

What was the cultural climate at the time?

People were switching fields a lot. I think that the war brought that about to some extent. By the time people came back from the war, they were mature and knew that they didn’t want to just go into some regular thing. So they went into design or crafts instead. A lot of the designers had their own shops in Beverly Hills, like Van Keppel and Green. They would manufacture things and sell them in their own shops and also be decorators too. This kind of crossing over was going on a lot.

I imagine the G.I. Bill of Rights helped with that.

Absolutely. The G.I. Bill of Rights gave people the ability to go back to school. Time was so much in my favor in this whole thing, because there was a kind of fluidity that existed in the furniture field because people were coming back from the war and beginning to design or manufacture. That was the case in point for Paul Tuttle, who was one of our most interesting designers.

Do you think this “fluidity” was more present in California than other parts of the country?

California seemed to be the place of the future. It was different from the rest of the country. The manufacturers were much more experimental, and there were a lot more people who were here out of the excitement of the place and maybe not wanting to do something that had been done before. It was clearly a step away from the Bauhaus. I think it also existed in a way that it did not exist in New York.

What was it about California that was so special?

I think the quality of light in the West made people think a little differently. As you travel West through the country, there’s something about the light that changes just about when you hit Arizona. It’s not the same as in the East. It does something different to people’s spirit and to their way of looking at things. It was also the beginning of industrial design being accepted as a discipline. People like Henry Dreyfuss and Niels Diffrient really enriched the situation here. And then there were the European émigrés—not just architects and designers but writers and composers as well. Los Angeles had been a kind of Western outpost until then. The influx of Europeans absolutely brought California into the twentieth century.

“California Design” wasn’t just design, though. Wasn’t there also a big emphasis on crafts?

I got really hung up on the crafts movement. And the same factors that impacted the design world also had a big effect on crafts. Ceramics, for instance, started being offered at the college level. It was no longer a trade thing and began to be looked at as a conceptual medium. This totally changed the field. In the beginning, there was a definite break between arts and crafts. The thing that made the difference was when some of the crafts people crossed the line from the useful to the expressive object.

Who was doing the most interesting crafts work at the time?

Oh, there were hundreds, but I’m thinking especially about the work of Peter Voulkos. He was such a compelling, amazing personality. He was at the Otis College of Art and Design [in Los Angeles] in the ceramics department throwing these enormous pots, which had a certain macho quality, so that just fascinated everybody. He was the one who really broke down that snobbery between the fields, because he made ceramics idea-driven. It became “I’m not making a pot to pour liquid out of, I’m making a work of art.” I think some artists and architects still had a slightly superior sense of their role in the world, though.

Like who?

Some of those modernist purists had this very hard, East Coast aspect and didn’t take crafts seriously. [The influential magazine] Arts & Architecture liked to be very exclusive, and John Entenza, the editor and publisher, didn’t like the crafts movement. He didn’t understand the amazing things that were happening—he thought of it as “artsy-craftsy.” But the crafts movement was there, whether John liked it or not. Of course, he still attended all the openings at the museum, because everybody did. Our shows became the meeting place for all the top designers and architects at the time.

The exhibitions obviously got a lot of local attention, but what about in the rest of the country?

We had enormous press coverage—that was something that had not happened before. The main person who helped on it was this woman here in Pasadena who had been a great fashion model, Elizabeth Hanson. She was a very good friend of mine and, through her years in New York as a top model, knew all of the magazines. She was the one who told me it was just ridiculous to have these big shows and no coverage. So we really did move on that area. We got into every magazine you could imagine—even Vogue.

“California Design” ended with your bicentennial show in 1976. Do you think things have changed a lot since then?

One of the points of having the shows was to highlight people who had another value system and weren’t just into money, money, money. Now even in California we’ve gotten very concrete, like everyone else. I miss the fluidity we had back then. I quiver whenever I think of that period. It simply was a fascinating time.