Exhibition

Modern Mastery: Hafu Matsumoto’s Bamboo

In 1933 the avant-garde German architect Bruno Taut traveled through Japan and saw examples of contemporary bamboo weaving. In his writings, he mentioned two masters of the craft: Tanabe Chikuunsai and Rokansai Iizuka, noting that Rokansai’s work was “modern.” Taut had designed the pineapple-shaped glass pavilion for the 1914 Werkbund exhibition in Cologne with the idea that a building could demonstrate the geometries of nature. It is intriguing to think he felt a kinship to an artist of woven basketry from a culture and a country so far away from his own. Like Taut, Rokansai was experimenting with the imaginative possibilities of a traditional material while honoring the organic design of nature. In his lifetime, he achieved outstanding proficiency with both the aristocratic as well as the less formal styles of bamboo weaving, but he became famous for a new technique of flattening and bending bamboo to produce the effect of what is known as wabi-sabi, beauty in imperfection.

Noshitake bamboo basket Sakimori (Soldier), 2017. Courtesy Ippodo Gallery.

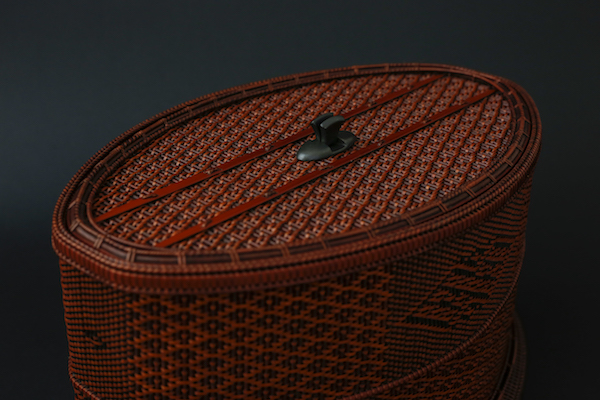

Hafu Matsumoto, whose work is currently on view at the Ippodo Gallery through July 7, is a disciple of Rokansai’s son Shokansai Iizuka. He came to apprentice with Shokansai in 1972 when he was twenty years old but he has said, “My teacher is always in my head, always giving me a push to be better.” The work on display represents all three styles of bamboo art, ranging from a Sashiami Mayfly decoration box with intricate embroidered plaiting to the more irregular white bamboo flower basket woven with free style hexagonal plaiting and finished with a wrapped handle.

Sashiami Mayfly decoration box, 2017. Courtesy Ippodo Gallery.

Bamboo Exposed: Mastery in Modernity of Hafu Matsumoto, however, is centered around his striking Noshitake series: baskets and vases constructed from wide, curved strips of bamboo that are given shape through a process of splitting the stalk, chiseling and shaving it, then soaking it in boiling water. When the thinned-out bamboo has softened, the artist, wearing gloves for protection, pushes and pulls and ties it into a shape that is a product of both the artist’s and the material’s intentions. To the Western eye, the result demonstrates a freedom of form and simplicity that appears totally modern. In some of the pieces, like Angu (Temporary Palace) which folds into an elegant open box, the bamboo has been gently coaxed into a subtle, unpretentious, but bold design. As the title suggests, the piece can be thought of architecturally with slivers of space showing through the unattached walls.

‘Fuhaku’ God of Wind, 2017. Courtesy Ippodo Gallery.

Other pieces graphically demonstrate Matsumoto’s physical struggle and excruciating sensitivity to the challenges presented by his material’s vitality and its resistance (it’s interesting to note he has studied martial arts his entire life; first kendo, which he began as a child, and more recently laido, the art of opening and closing a Japanese sword). One of these masterful pieces, Sakimori (Soldier), stands vertically with assurance, almost two feet high, and the band of twisted and knotted bamboo seems to be exploring the essence of space in buckles and loops like abstract or even minimalist sculpture. Fuhaku (the God of Wind) is a more horizontal, cloud-like piece that brings to mind a bundle of tumbleweed.

Noshitake bamboo flower vase Angu (Temporary Palace), 2017. Courtesy Ippodo Gallery.

But there’s a difference between Western aesthetics and the philosophy of Take (bamboo)-Kôgei (craft) which is the foundation of Matsumoto’s art. As he put it, “When I make something and I have a form in front of me, I think of it as ninety percent there, and it’s important that it remains ninety percent. To continue to drive, that is what makes it a piece.” His objects are always premised on use and his baskets are never intended to be merely beautiful objects. Rather they ask to be opened up, to have flowers placed inside, to be touched, experienced with all of the senses. For Matsumoto, the work exists in a continuum that begins with his relationship to nature and honors the ongoing tension and spirit of the material that guides him. In this way, the art is not about modern abstraction but about the path of his struggle and his acceptance of incompleteness and impermanence.