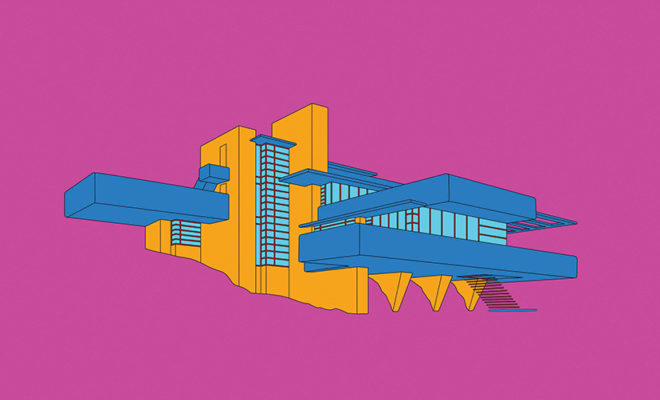

A rendering by Michael Craig-Martin of Fallingwater by Frank Lloyd Wright. © Michael Craig-Martin, 2019, photograph by Peter White, courtesy of Alan Cristea Gallery.

A rendering by Michael Craig-Martin of Fallingwater by Frank Lloyd Wright. © Michael Craig-Martin, 2019, photograph by Peter White, courtesy of Alan Cristea Gallery.

Exhibition

Michael Craig-Martin Gives Color to the Everyday Objects in a New Exhibition

For several decades British artist Michael Craig-Martin has been exploring the way we perceive the quotidian objects that fill our lives, in search of the what he calls “the essence of things.” Now, at his exhibition, Present Sense, currently on view at The Gallery at the luxurious Windsor, an exclusive residential enclave in Vero Beach, Florida, it is possible to see how comprehensive this investigation has become. On display are his depictions of such ordinary objects as a laundry wire hanger, an iPhone, and even a credit card—all rendered in his trademark line drawings accented with bold, vibrant colors. The show, which is part of a three-year curatorial partnership between the Windsor community and the renown Royal Academy of Arts in London, is the largest grouping of Craig-Martin’s artworks to date, and includes prints and sizable sculptures, scattered throughout the Windsor grounds. We got the chance to catch up with the artist to learn more about his new show, which is on view until April 25.

An installation view of the exhibition. Courtesy of the artist.

PAUL CLEMENCE/MODERN MAGAZINE: What would you say is the main theme of your work?

MICHAEL CRAIG-MARTIN: It’s hard to describe. I am trying to make the act of looking at something transparent, looking at representation as if it is a surprise, as if a miracle! What interests me is the relationship between things and the images of them. When I make a painting of something, like a shoe for example, the first thing that comes to your head upon seeing it is that it’s a shoe not a painting, but the shoe isn’t there, it’s an illusion. Our ability to read these illusions is so powerful and so innate, we don’t even realize we are doing something absolutely amazing.

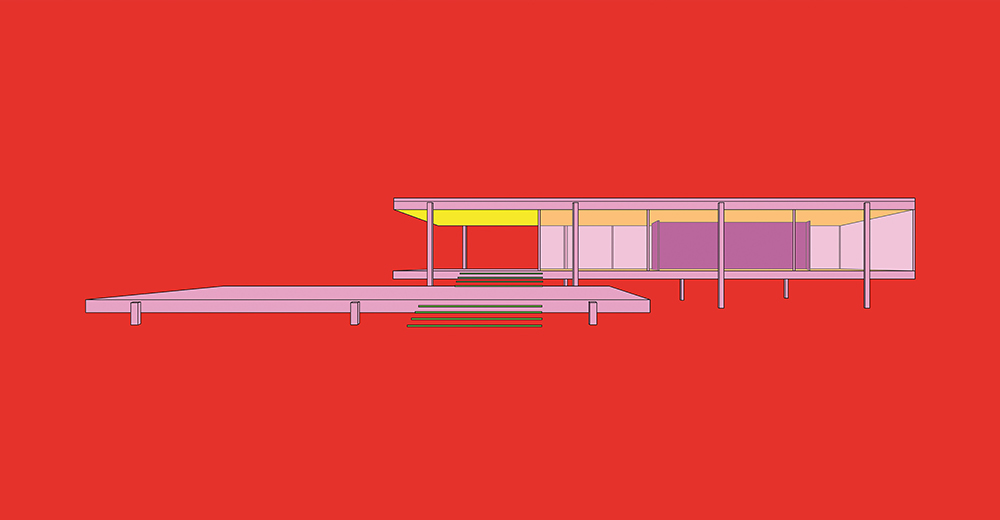

A rendering by Michael Craig-Martin of The Farnsworth House by Mies van der Rohe. © Michael Craig-Martin, 2019, photograph by Peter White, courtesy of Alan Cristea Gallery.

MM: You speak of translating the perception of these generic items into something particular. Could you elaborate on that process?

MCM: As soon as you make a painting of anything, or of anyone, it’s in the nature of art that you elevate its [the object’s] place in the world. In my work, I take ordinary things that are ubiquitous, which we are surrounded by—that we may think are beautiful or not, expensive or not— and then I try to take away all of those hierarchies and all the different attributed values, and simply draw attention to them in the most basic way. I try to look at these things that are really the expression of our culture, of our society. Just like when we go back to examine the ancient times, in Egypt or Greece, and try to understand that society through the things they made, through the artifacts.

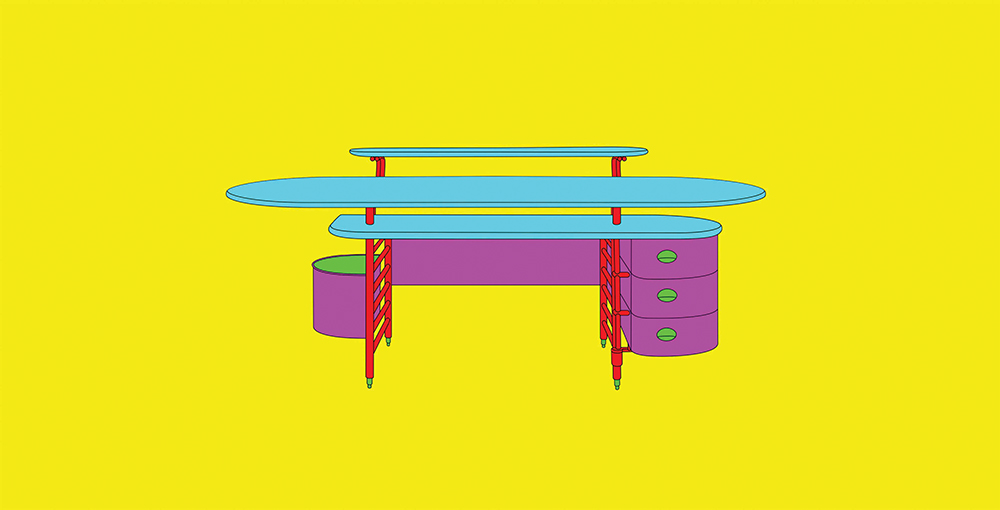

A rendering by Michael Craig-Martin of a Frank Lloyd Wright desk. © Michael Craig-Martin, 2019, photograph by Peter White, courtesy of Alan Cristea Gallery.

MM: What is the role of color in your work?

MCM: The drawings are absolutely straightforward, I never distort them. I just draw exactly what I see. Color represents everything else to me: it’s emotion, it’s having free expression, it’s passion. It’s all the things the drawings are not—the illogical, the non-sense, the personal layer. Color is part of seducing the viewer—bringing awareness to the power of that present moment.

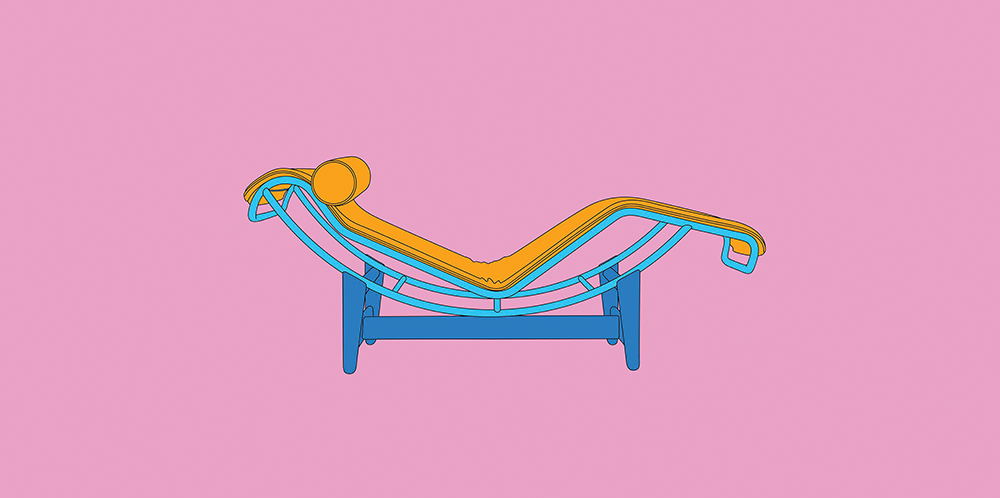

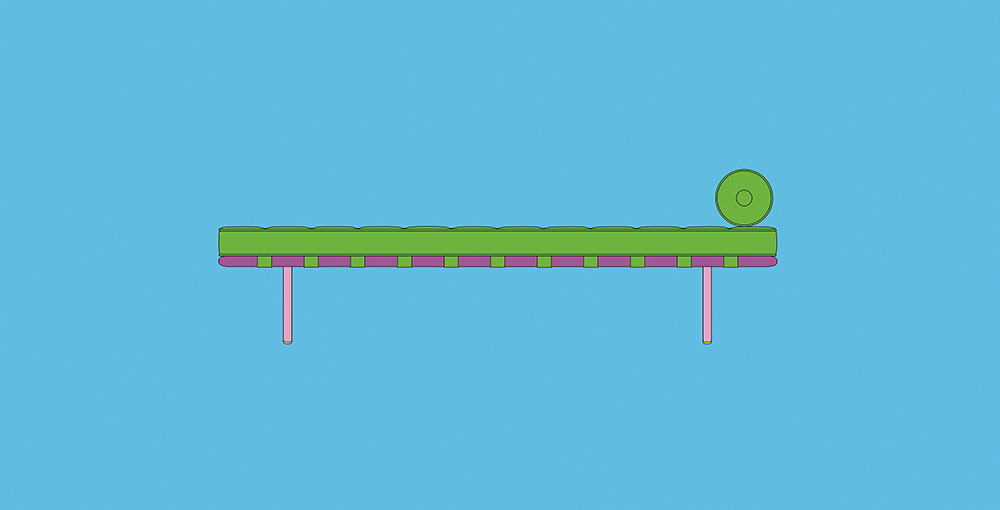

A rendering by Michael Craig-Martin of a Le Corbusier chaise. © Michael Craig-Martin, 2019, photograph by Peter White, courtesy of Alan Cristea Gallery.

MM: From your brightly colored gallery wall installations to your collaborations with architects such as Herzog & de Meuron, John Pawson, and David Chipperfield, you’ve always had a special connection to architecture. One of the highlights of the show is the series celebrating the legacy of four iconic pieces of modern architecture. How did this series develop?

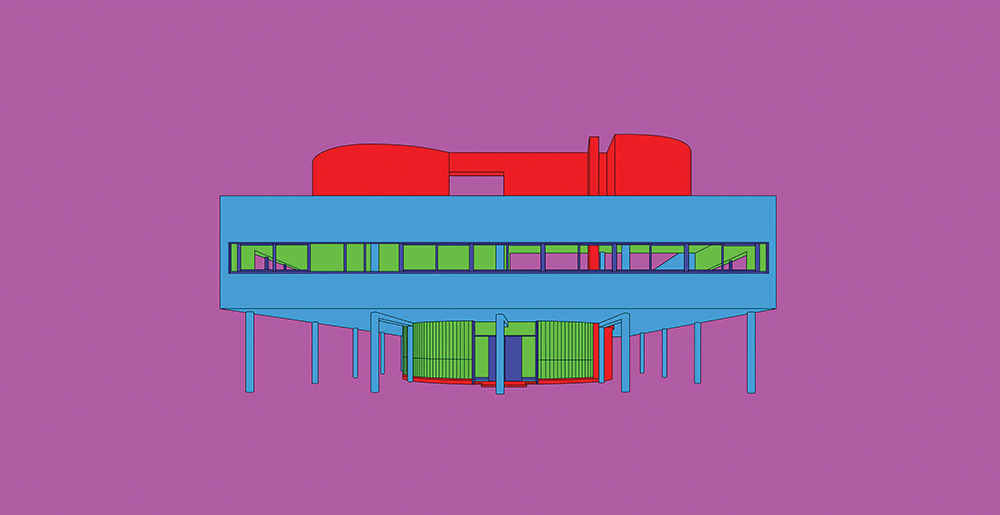

MCM: My idea was to choose the key designs of the twentieth century that gave us the appearance of what the modern world would look like. There is the Farnsworth House by Mies van der Rohe, Fallingwater by Frank Lloyd Wright, Villa Savoye by Le Corbusier, and the Schröder House by Gerrit Rietveld.

A rendering by Michael Craig-Martin of a daybed by Mies van der Rohe. © Michael Craig-Martin, 2019, photograph by Peter White, courtesy of Alan Cristea Gallery.

MM: What appealed to you about these projects?

MCM: It was interesting that the architects—one French, one American, one German, and one Dutch—are all from different countries and cultures, but together, their works constitute the essence of modernism, and one hundred years later they still look modern.

A rendering by Michael Craig-Martin of Villa Savoye by Le Corbusier. © Michael Craig-Martin, 2019, photograph by Peter White, courtesy of Alan Cristea Gallery.

MM: Being immersed in so much design, have you been tempted to do it yourself?

MCM: Oh, yes, I think of designing a chair all the time, and have done loads of sketches but none that have satisfied me. You see, for me, creativity in terms of invention is the realm of the designer, and creativity in terms of observation is the realm of the artist.