COURTESY OF WALT DISNEY COMPANY

COURTESY OF WALT DISNEY COMPANY

Feature

Memphis et al. explained

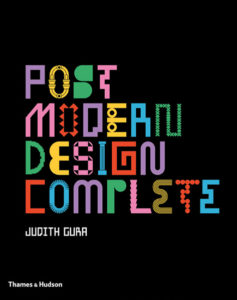

Postmodern Design Complete:

Design, Furniture, Graphics, Architecture, Interiors by Judith Gura • Thames & Hudson, $95

THEY’RE BACK. The searing hot colors, the jarring patterns, and over-scaled motifs—all the signature features of postmodernism, the radical design movement that burst into prominence in the 1980s, have reappeared in fashion, architecture, and the decorative arts, again bringing excitement and enervation in equal measure. Now, to lend some sense and context to the discussion, comes design historian Judith Gura with a new compendium, Postmodern Design Complete: Design, Furniture, Graphics, Architecture, Interiors. We asked her a few questions about postmodernism, then and now:

MODERN MAGAZINE: Is there a concise and comprehensive definition of postmodernism?

Judith Gura: Charles Jencks, the man most responsible for articulating its theory, took a book to define postmodernism, but I’ll try. In terms of what it was: postmodern (in design) was the period that followed mid-century modernism and the International style, and it was a reaction to modernism’s failures. Modernism had lost touch with the public in failing to communicate, it hadn’t kept its promise of making life better, and it had abandoned history. In terms of what it looked like: postmodern architecture is characterized by classical motifs and elements of vernacular styles, and often introduces color. Postmodern furniture and objects use jazzy colors, clashing patterns, and an eclectic mix of materials in quirky pieces that often prioritized form over function.

For the uninitiated, describe the reaction when postmodern design first appeared in the early ‘80s at venues like the Milan Furniture Fair.

Shock and awe, to say the least. People didn’t know whether to love it or laugh at it, and they did both. Everybody talked about it, but for the most part, nobody took it seriously—though the designers were absolutely serious in what they were trying to do and say.

COURTESY OF WRIGHT

Why does it continue to disturb some and delight others?

Postmodern design isn’t a shrinking violet. Furniture is generally expected to sit quietly in the background, but this almost shouts for attention. It’s very much in-your-face, which makes some people uncomfortable. And to be practical, it’s not easy to integrate into a room. Postmodern pieces don’t really play well with others.

Can you point to any causes for the recent resurgence in interest in postmodernism?

There’s a general rule of thumb that style revivals come after about thirty years. It happens most visibly in clothing styles. It began to happen with postmodernism over the past decade, and even earlier. There was a 2001 exhibition at London’s Design Museum, and a few others, but a major exhibition opened in 2011 at the Victoria and Albert and really put the revival into high gear. There’s a whole generation of consumers who weren’t born when postmodernism came around the first time, and they’re seeing it with fresh eyes. Next to lively postmodern pieces, conventional designs can look a little dull. And those who remember the original are now viewing it with the perspective of distance, and can appreciate how much it changed the climate of design.

How is postmodernism evolving? If it becomes accepted or “normal,” is it dead?

Not at all. I think it’s being absorbed into a broader vocabulary of design, which is a healthy sign. Its most important influence, I believe, was in freeing up designers to try doing things differently, to break with tradition, to find their own style—and not to be afraid if it doesn’t follow established norms, or anyone else’s definition of good taste.