Design

Man of Action

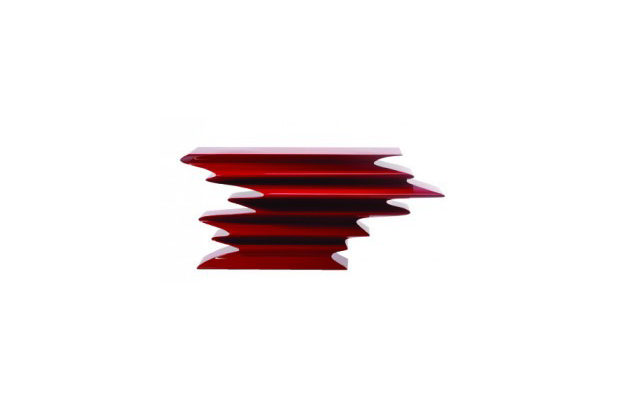

You might be tempted to wonder whether Hervé van der Straeten believes in the laws of physics. Stunning gravity-defying consoles, for example, are one of the French designer’s fortes. His “Psychose” is an almost comic strip-like representation of speed in furniture form: a zoom of accordion waves of red lacquered fiberglass that seems to be in motion; “Crystalloide,” inspired by the process of crystallization, features an avalanche of tumbling blocks of gleaming nickel on brass in one version, and silver in another; the white marble slabs in the console called “Kashmir” are arranged in a startling asymmetrical composition.

Hervé van der Straeten (left) created his “Psychose” console of 2008 is of red lacquered fiberglass.

These high-wire demonstrations of equilibrium are matched for vivacity only by van der Straeten’s masterful mixes of materials and textures. The “Kyoto” buffet combines exteriors of obsidian on silver-tinted leather plus polished patinated bronze baguettes, drawers, and cabinets lined in oxidized chestnut sheathed in leather in matching tones, and a top and legs in black Belgian marble. One of van der Straeten’s armoire designs has doors that marry amboyna burl with ebony; while the “Buffet Bi-Colore” is a mélange of bronze-patinated lacquered wood with a parchment top, bronze baguettes, and interiors of sycamore.

At forty-six, the École des Beaux-Arts-trained designer has produced a vividly original array of unique pieces and limited editions (each of eight to forty pieces) of furniture, lighting, consoles, mirrors, and jewelry that attracts art collectors and, reportedly, such fans as Madonna, Tom Ford, Mick Jagger, and Diane von Furstenberg. His pieces regularly appear in the haute decors created by a swathe of high-flying decorators—Jacques Grange, Alberto Pinto, François Catroux, Peter Marino, Juan Pablo Molyneux, and Thierry Despont, to name a few. Other creations include the Dior “J’adore” perfume flacon and Saint-Louis’s “Excess” crystal collection.

In Paris his collections are shown in his own newly reconfigured 2,800-square-foot gallery space in the Marais and the Paris gallery Perimeter Art & Design, which introduced his tipsy “Twist” candlesticks-cum-centerpiece at last June’s Design Miami-Basel fair. In New York his designs are represented by Ralph Pucci International and the gallery Maison Gérard, and, in Brussels, at Pierre Bergé’s gallery and that of Flore de Brantes, who took van der Straeten’s pieces to both the 2010 TEFAF Maastricht and BRAFA fairs. In the inaugural exhibition, opening November 10, at her new Brussels gallery, de Brantes is featuring his designs along with her signature mix of contemporary art and eighteenth-century antiques.

“Hervé is a perfectionist, a perfectionist in design, but also in the quality of the execution of his work,” de Brantes explains. “That is what makes him unique.”

To see behind the scenes of his exceptional designs, I hop a taxi to the amusingly named “street of the future” (full of warehouses and workshops) in an eastern Paris suburb where the designer’s atelier has been certified as a “Living Heritage Company” by the French Ministry of Culture—an acknowledgment of the studio’s rarified knowledge of cabinetmaking and bronze-working techniques. When we meet in the courtyard, van der Straeten is clad in an impeccable crisp white shirt and black jeans. If I was expecting the soft rasp of a chisel on wood—well there is that, too, in the cabinetry workshop—it’s soon blotted out by the screaming whine of a saw slicing through metal or shaping angles in the bronze atelier. In an ambiance more car body shop than artist’s studio, machines share space with the workbenches and tools of each artisan.

In his office opposite the small jewelry atelier, we flip through the pages of a small notebook where van der Straeten’s designs are born in free form, though his sketches are surprisingly neat and clean for preliminary mock-ups. He compares the drawings to doodles or Dadaist automatic writing, “a sort of stream of consciousness drawing that comes out of my head,” he says. Later, he may see the inspirations of an exhibition, an artist, architecture, a material, or a concept of movement like the undulating red waves of “Psychose.” “My furniture is solid, massive and very geometric. The chandeliers, mirrors, and consoles tend to be sculptural with a lot of movement and freedom. I like to discover different periods and artists, you learn from them,” he says. Favorites include Gerrit Rietveld, Kazimir Malevich, Eileen Gray, and Oscar Niemeyer.

When we come to a drawing of the jumble of cubes that became the console “Crystalloide,” he explains, “It looks random, but inside each box is a structure that supports it.” When I ask if he was ever an engineer, the response is a revelation. Both his father and brother are engineers and his early studies were in the same discipline. “By the age of eighteen, I knew technical design and how to do a 3-D program in my head. So when I design something like this, it’s total freedom, but mixed with that I know what is going on behind and exactly what I am drawing.”

He knew engineering was not his future. “I had fun designing and was already creating jewelry,” he recalls. “It started showing up on the fashion runways and in the magazines. I had my own company and clients like Bergdorf Goodman when I was nineteen and still at the Beaux-Arts.”

Furniture and objects were always an ambition, but the success of his jewelry took up ten years. “Working with metal jewelry was and is like a laboratory for studying shapes. My chandeliers, sconces, and mirrors are precious in a way that comes from jewelry,” he says. Motifs like irregularly shaped links of a chain and clam-sized beads appear in his lighting and mirrors. He moved on to working with bronze and brass on a different scale, first small objects, mirrors, and lighting, then furniture in 1998 when he opened his gallery.

From the structure pictured in his sketch, he selects materials, colors, and the scale to reinforce the concept of each piece. “Red lacquer for ‘Psychose’ because it gives a dynamic to the waves, and contrasting materials like mixing a purple lacquer with parchment or a mix of a sculptural material like bronze with an industrial anodized aluminium in the convex ‘Blue Sorcière’ mirror,” he says. “It’s like making a sauce of rosemary, butter, and chicken stock, then adding a few drops of vinegar. I want to push the boundaries in materials, shapes, ways to create.” He is currently using myriad colors of Perspex and mixing iridescent glass with marble.

On a tour of the ateliers, we stop before a piece that will be part of his upcoming gallery collection: a custom cabinet whose ripples of sycamore will be covered in parchment. “We first make a sort of blueprint [based on his design sketch] on scale with the real size of the finished piece; then a model in medium wood on the same scale, and we use that model to correct the proportions,”

van der Straeten explains. “It can demand tens or hundreds of hours of work. Everything is extremely precise. When you are working with such precious woods you can’t afford to make

a mistake. We don’t.”

We watch as craftsmen assemble the piece by hand, shaving the wood to shape a cabinet foot. “Each piece is cut out, filed, and planed,” he continues. “Working the solid wood and applying the veneer onto the wood is done by hand. We work with lacquer and parchment specialists, but eighty percent of things are done here. It’s rare to see that in an atelier today.”

Like furniture couture, van der Straeten’s designs are made of sumptuous materials with hidden details that are vital to the quality of pieces he describes as “conceived to last a long time.” The wood elements of a gigantic mirror lacquered with gold leaf are individually beveled at 45 degrees before they are lacquered “so if the wood starts to move, it will move in the angle. The surface of the lacquer will remain fine, even, and never crack.” He opens the doors of a sideboard to be covered in goatskin or lambskin parchment on a white fabric. The dovetail assembly means the hinges are recessed and concealed. “What you see is the sycamore. I like the inside to be as beautiful as the outside,” he remarks.

And he likes to surprise—most of all himself. “My work evolved from the pleasure I get from designing, pushing myself further,” he says. “Basically my job is to give as much pleasure as I get to the people who buy my pieces.”