DWAYNE RESNICK PHOTO/COURTESY MARK MCDONALD

DWAYNE RESNICK PHOTO/COURTESY MARK MCDONALD

Design

Lost and Found

THE SAGA OF STEFAN KNAPP’S BOLD FACADES FOR ALEXANDER’S DEPARTMENT STORES

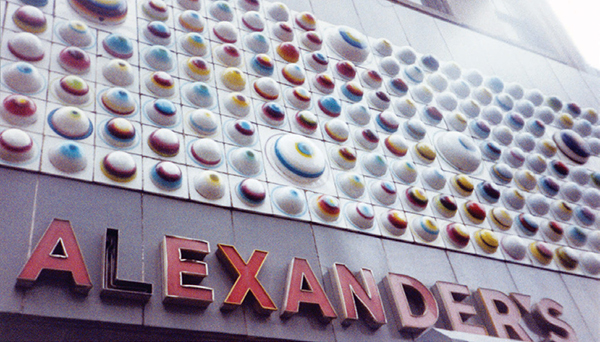

WHEN THE ICONIC FACADE DESIGNED by the Polish-born British artist Stefan Knapp was installed on the sides of the Alexander’s department store in New York City in 1963, it was a turning point. Rarely had a sophisticated and large-scale work by a modernist sculptor been displayed in such a decidedly urban setting. Dominating the heavily trafficked corner of East 58th Street and Third Avenue, the mural was composed of more than four hundred square white-enameled panels, each with a delicately colored dome. The various colors on each dome looked like the rings around Saturn. According to The New Yorker’s former architecture critic Paul Goldberger, “the whole thing looked like a billboard filled with eyeballs or hubcaps or salad bowls. It was easily the most monumental piece of Op art in New York.”

Stefan Knapp’s 280- panel mural (a portion is shown above) was originally mounted on the exterior of Alexander’s department store in Paramus, New Jersey. Portions are now on display at the Art Factory in Paterson, New Jersey. | COURTESY ART FACTORY

Knapp’s extraordinary mural was not only an accomplishment in terms of vision and size, it was a technological breakthrough. Working in a giant studio outside London, Knapp had earlier discovered how to mount enamel on zero carbon steel rather than copper, its more traditional base. (The latter is used often in enamel jewelry.) Given the advantages in both size and durability offered by steel panels, Knapp was freed to work on a scale hitherto not possible. And thus the sculptor, who by the late 1950s was showing regularly in London and Amsterdam, was to land such commissions as the seventeen large enamel murals for London’s Heathrow Airport.

Knapp’s wife, Cathy, in remarks later published in the magazine Glass on Metal, would recall that he “cleaned the steel chemically, then washed it and quickly sprayed it with a cobalt enamel grip coat. This was a pale grey biscuit color before firing but after an initial firing at 820 degrees centigrade became a shiny black color. He then poured a coating of opaque white enamel over the panel and when it was dry would draw his cartoon, sgraffito style.”

Another Stefan Knapp mural adorned an entrance on 58th Street and Third Avenue to the Alexander’s store in Manhattan for more than three decades, until it was disassembled in 1998 when the store was demolished. Many of the panels were rescued by the building salvage company Olde Good Things. | DAVID M. SANDERS PHOTO/FLICKR

Luckily for Knapp, George Farkas, the owner of Alexander’s and a notable art patron, saw the murals at Heathrow. After opening the first Alexander’s in the Bronx, he was, by the early 1960s, expanding its reach throughout the New York area. He first commissioned Knapp to make a mural for his store in suburban Paramus, New Jersey. “Once touted as the largest public mural in the world,” wrote the New York Times in 2015, it consisted of 280 panels weighing 250 tons mounted on a giant exterior wall of the store, near the intersection of the Garden State Parkway and New Jersey State Highway 4. After assembling it in his studio—according to Glass on Metal, Knapp was photographed using skis to traverse it while he applied the enamel and paint—the mural was shipped to Paramus and installed.

An instant success, the Paramus mural inspired Farkas to commission additional artwork for the company’s new store in Manhattan. After all, Alexander’s, a stripped-down chain that offered no perks such as home delivery but made up for it with consistently lower prices, was now going up against such retail giants as Bloomingdale’s and Macy’s. Farkas needed his flagship to stand out. He initially thought of having an even more prestigious artist create art for the exterior: Salvador Dalí. The latter’s outlandish designs included giraffes with typical department store drawers suspended from their necks hanging out over the street. Farkas soon realized that Dalí’s ideas were impractical. The artist, in a nod to Knapp’s sculptural techniques, suggested that the latter could enamel the giraffes. Knapp refused. In the end Knapp was awarded the entire commission. (The “Dalí affair” did not fatally damage the Spanish surrealist’s relationship with his New York patron, who framed his design drawings and hung them in the boardroom.)

A close-up of the colorful enameled-steel domes salvaged from Knapp’s Manhattan mural. | DWAYNE RESNICK PHOTO/COURTESY MARK MCDONALD

Knapp’s 1963 mural so pleased Farkas that it led to yet more commissions, including a mural for the branch of Alexander’s on Long Island. Sadly, Alexander’s went into bankruptcy in 1992; when the Manhattan store was torn down in 1998, Knapp’s iconic mural appeared destined for the scrap heap. During demolition, construction crews reputedly offered individual squares to passersby as souvenirs. According to George Farkas’s granddaughter, the uptown restaurateur, Georgette Farkas, members of the family didn’t expect to see this particular and rare work again, not even small sections of it. No one dreamed any part of it would ever have any value.

But the building salvage company Olde Good Things (according to its website, it is “the place of the architecturologists”) managed to secure many panels of the enameled squares. Not long afterward they took some of them to their booth at the flea market on West 25th Street.

The design dealer Mark McDonald, whose clients include the Brooklyn Museum and the Museum of Arts and Design, happened to be passing by. “When I first came to New York in the 1980s I worked at the antiques dealer Lillian Nassau and walked past Alexander’s twice a day,” he recalls. “So I knew exactly what I was looking at. I could hardly believe it.” Soon after, McDonald ventured to Olde Good Things’s main store and purchased about a hundred of the remaining Knapp squares. In the years since he has sold many of them; one client, the well-known collector Barbara Jakobson, installed seventy-six of the small squares and four of the larger ones in her Upper East Side garden. And so these unique pieces of mid-century sculpture, shiny exemplars of Knapp’s distinct style, have gained a new life and a new, albeit more private, set of admirers.

Olde Good Things also salvaged several enamel and steel panels from Knapp’s mural for the Long Island branch of Alexander’s, and they are now on display at the firm’s Madison Avenue location. | COURTESY OLDE GOOD THINGS INC.

But they are not the only parts of Knapp’s Alexander’s legacy to live on. Last year, after being kept in storage following the demolition of the Paramus store in 1997, many of those panels were acquired by the Art Factory, an artists’ studio space in Paterson, New Jersey, where they are now on display. Olde Good Things secured a thirty-two-foot-long set of fourfoot- high panels from the Long Island branch’s mural; they’re currently mounted in its store on Madison Avenue, priced at $26,500. A lofty price, but thanks to awareness of Knapp’s innovative design techniques—and the various murals’ curious histories—even portions of them are now much sought after.

Hard to believe that barely two decades ago Knapp’s work was in the hands of a wrecking company and almost on its way to a sorry end in a scrap yard.