Liza Lou’s solo show Classifications and Nomenclature of Clouds inaugurates Lehmann Maupin’s new 10th Avenue outposts. Matthew Herrmann Photo; Image courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul.

Liza Lou’s solo show Classifications and Nomenclature of Clouds inaugurates Lehmann Maupin’s new 10th Avenue outposts. Matthew Herrmann Photo; Image courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul.

Architecture

Liza Lou Debuts at Lehmann Maupin’s New Chelsea Outpost

It’s only fitting that Liza Lou’s latest body of work should inaugurate Lehmann Maupin’s new Peter Marino-designed outpost in Chelsea. Soaring gallery spaces play host to the artist’s monumental tapestries while a black box on the basement level provides the perfect conditions to screen films. Classification and Nomenclature of Clouds, on view until October 27, is the Los Angeles-based artist’s first large-scale exhibition in New York in over a decade, and encompasses a variety of media from painting and drawing to sculpture and film.

Marino’s design for the new multi-level venue is no less harmonious. A mezzanine seamlessly cantilevers between two column-free, double-height gallery spaces. The long balcony cuts into both spaces, allowing visitors to experience works from different angles. One such piece that benefits from this expansive space is Lou’s The Clouds—an installation comprised of a grid of six hundred beaded cloths in various textures and hues. The sheer scale of the work can only be understood by witnessing it from above.

The New Peter Marino-designed space includes various exhibition spaces that are conducive to different scales of work created by the gallery’s wide roster of talents. Matthew Herrmann Photo; Image courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul.

An additional third-level alcove offers glimpses of the nearby High Line. “For Lehmann Maupin, we created a series of variable spaces and views,” Marino explains. “Each gallery space provides unique opportunities for artists whose exhibitions differ wildly in scale and medium.” The celebrated architect has known the gallery’s founders Rachel Lehmann and David Maupin for decades and is familiar with their diverse roster of artists.

The new Lehmann Maupin outpost in located within the Getty building, a new 6 unit residential project in the heart of Chelsea’s gallery district.

This sober yet adaptive aesthetic carries throughout Marino’s entire eleven-story Getty project in which the new gallery is located (the building also includes six apartments and the Hill Art Foundation). “This can be seen in the façade, where the offset metal and glass panels are of varying dimensions and reflect the interior’s individual identity and diverse floor-plans,” Marino says. Located on one of the last remaining parcels of Chelsea’s gallery district—a former industrial zone—the new structure hints at its heritage, with such gestures as twelve-inch-wide, solid oak floor planks. The building’s name is also a nod to its predecessor, the infamous Chelsea gas station, which was the site of the occasional art installation.

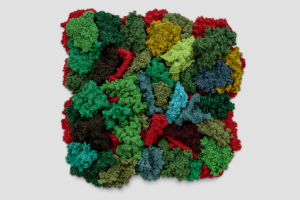

Lichenform III by Liza Lou. Joshua White Photo; Image courtesy of Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul.

Alluding to industry in her own way, Lou’s latest multidisciplinary project derives from the artist’s long-standing fascination with the cultural, social, and historical implications of labor itself. In her recent work, the use of glass beads reveals different aspects of this ongoing exploration. “Thought rich in association, I’m always trying to push the material outward and toward something universal, trying to set it free from its cultural baggage,” she explains. “Glass beads interest me in the sense that they are a humble material.”

Lou teamed up with women artisans in Durban, South Africa, to stitch together the beaded cloths used in the current exhibition. This material was then brought to her Los Angeles studio, where she experimented with and implemented a bespoke technique. Painting over and partially smashing the beads, the artist developed a sfumato effect in her compositions, resembling clouds as they appear in her homes in both Durban and Los Angeles.

Liza Lou. Mick Haggerty Photo; Image courtesy of Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul.

The tension between collective and isolated practice has been a common theme throughout her career. “My tendency toward long-term, labor-intensive work has to do with an understanding of work as prayer—my religious upbringing taught ‘hands to work, heart to God,’” Lou explains. “Zooming outward, I became interested in working in parts of the world where working in community has its own personal associations and meanings.”