Courtesy Hawke's Bay Tourism.

Courtesy Hawke's Bay Tourism.

Design Destination

Kiwi Cool: Design from below the Equator

It will come as news to many—even those steeped in the history of modern design movements—that New Zealander Garth Chester (1916–1968) invented the first cantilevered plywood chair, the Curvesse, in 1944. And yes, before reaching for those reference volumes to debunk this assertion, it’s true: Alvar Aalto molded laminated plywood for his F35 chair as early as 1930. Yet Chester conjured what was, in the words of modern architecture and design scholar Douglas Lloyd Jenkins, “an innovation in furniture design that had at that point yet to be seen anywhere in the world.” Designer and writer Michael Smythe explains why in his book New Zealand by Design: “Where Aalto had molded the cantilever support and armrest separately from the seat and backrest, Chester had done it all in one hit.”

Chester’s mystifying obscurity—along with that of other Kiwi designers and architects such as Edzer (Bob) Roukema, Ernst Plischke, and John Critchton—can be attributed to many factors, only the most obvious of which is the country’s remoteness from concurrent modernist movements. Nevertheless, the market for their work is growing. James Parkinson, who began organizing New Zealand modernist sales while at Webb’s, the Auckland auction house, remembers his first foray into the field twelve years ago, which took place “in front of a crowd of blank faces.” Now, he notes, there are one or two a year at Webb’s, and he mounts three at his own Art and Object auction gallery, also in Auckland. “At the moment I have people lining up to buy Curvesse chairs in good condition.” And, he adds, an expat New Zealander in New York “has bought every Roukema chair I’ve sold.”

Jenkins, author of At Home: A Century of New Zealand Design and director of MTG [Museum, Theatre, Gallery] Hawke’s Bay in Napier—devoted, among other things, to telling the story of Kiwi mid-century modernism—is arguably the leading scholar of a field he calls “a quirky little version of modernism.” If it can be said to have had a golden age, it occurred from about 1948 to 1960, with its most idiosyncratic designs emerging during the 1950s.

The influence of Scandinavian modernism is incontrovertible. Sweden and New Zealand, says Jenkins, “were both small liberal democracies on the fringes of the world, and there was a sense we should align ourselves with the Scandinavian model.” Many did. Some, like Chester and Roukema, tweaked the genre in distinctive ways.

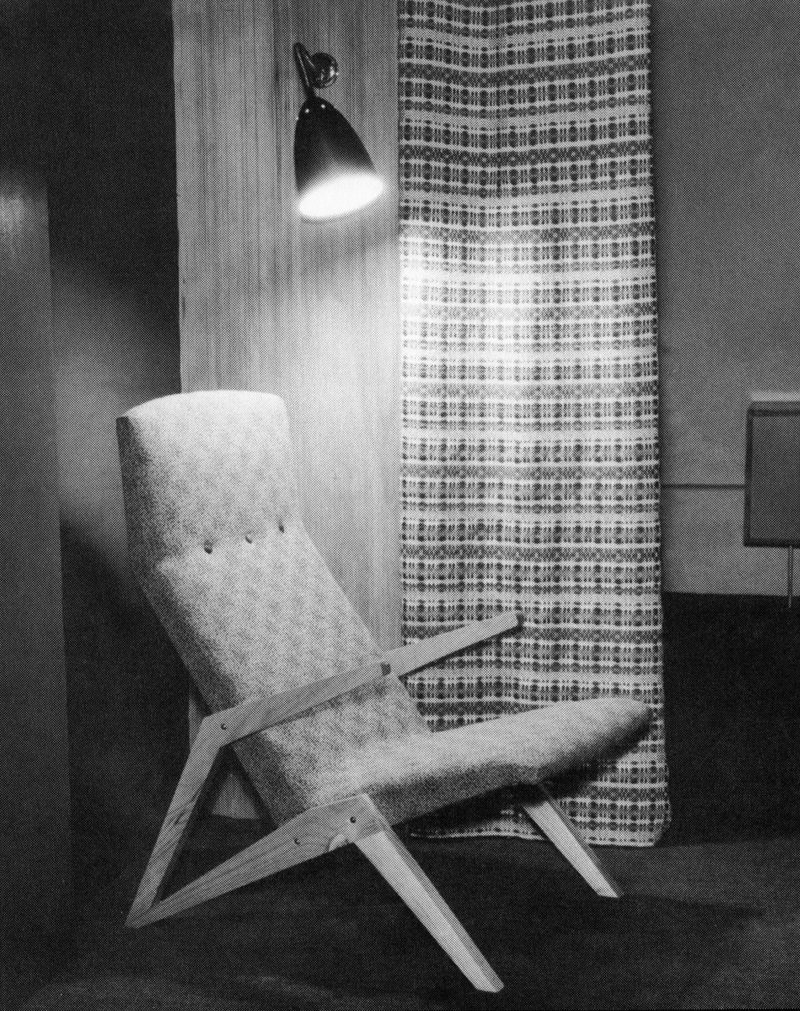

This bent plywood Curvesse chair, designed by Garth Chester in 1944, fetched $7,500 at auction. Courtesy Art and Objects.

The reason for imitation was not lack of imagination, but importation restrictions imposed by the second Labour government in 1957; reproduction became the only way of filling demand. Nevertheless, these Scandinavian style designs, notes Parkinson, beg the question “Why would you buy a Danske Møbler chair when you can buy a Finn Juhl chair for about the same price,” especially when overseas shipping is taken into account? (Danske Møbler was a New Zealand company started by Danish émigrés Kaj and Bente Vinter, later anglicized to Ken and Bente Winter.)

But New Zealand came by its European influences honestly. Many architects and designers fleeing the approach of Nazism arrived there in the 1930s. Roukema was born in Holland, Plischke in Austria, Tibor Donner in Hungary (he arrived as a twenty-year-old and trained at Auckland University College). Vladimir Cacala was born in Czechoslovakia, Crichton in Britain.

They employed local materials, and many of their designs were well made. Sometimes, however, the design requirements of Scandinavian style furniture did not jibe with New Zealand’s production capabilities, and results could be less felicitous. “Veneers in New Zealand were not very good,” says Emma Eagle, who, with husband Dan, owns the Auckland gallery Mr. Bigglesworthy (about half its offerings are by Kiwi mid-century designers). “Unless it’s solid wood, we don’t touch it.” Craftsmanship, she adds admiringly, was “hard won” because producers had to develop new skills.

Another issue for collectors is availability. About five hundred Curvesse chairs were made, but, says Jenkins, because some of the more interesting designs were crafted on demand by architects for the houses they designed, “many of these designers produced only twenty or thirty pieces. It’s not enough to really excite the market.”

Nevertheless, though prices have not yet breached the five-figure mark, they are escalating. “Five years ago you wouldn’t have even catalogued a Garth Chester chair,” Parkinson says. Now good examples of the Curvesse can easily bring close to $8,000.