Design

Hudson School of Cool

A RECENT WAVE OF ENERGY HAS transformed the historically vaunted Hudson River valley of New York into something approaching a model post industrial economy. Where towns like Beacon and Hudson were once centers of brickmaking and whaling, today their downtowns are a bustle of galleries and tech companies and artisans. Their outskirts are dotted romantically with triumphs of architectural preservation and locavore-driven farming. In a word, the Hudson valley is hip.

House 432, designed by Robert Siegel, sits on a hill on a 4-acre parcel in Katonah, New York. Paul Warchol Photo.

Modernism aficionados know the region as a crucible of progressive twentieth-century architecture. That experimentation dates to at least 1942, when designer Russel Wright and his wife, Mary, purchased the seventy-five acres in Garrison, New York, that would become Manitoga (featured in our Spring 2018 issue). Two years later, a collective of young New Yorkers invited Frank Lloyd Wright to plan a community in Pleasantville—what is today known as the Usonia Historic District. And in 1951 business executive Peter McComb asked Marcel Breuer (who had been designing Ferry House at nearby Vassar College) to create a residence for his family in Poughkeepsie, for which the architect would adapt his famous binuclear plan to include second-floor living space.

Yet the Hudson valley is rarely spoken of in the same breath as, say, New Canaan, Connecticut, which the Harvard Five transformed from country seat into cosmopolitan suburb beginning in the late 1940s. Nor has it been compared to farther flung oases of site-specific modernism, such as Fire Island, Sarasota, or Palm Springs.

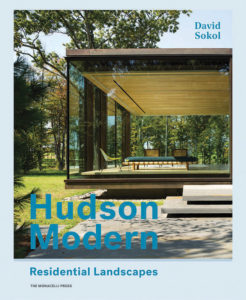

That perception is likely to change for those who go on a weekend jaunt to the region. Since the turn of the twenty-first century, the Hudson valley has come further into its own as a hotspot for high design. The forces of hipness that are energizing main streets have also boosted patronage of visionary architecture. And, not unlike the movements that gelled in Columbus, Indiana, or on Cape Cod in Massachusetts, these projects interpret modernist principles in a uniquely local, cohesive way—pairing Cartesian geometry with romantic landscape, embodying awareness of historic and vernacular buildings, and conveying a sense of humility that’s not entirely dependent on size alone. The following houses and studio buildings, featured in my new book Hudson Modern, published by Monacelli Press, exemplify the architectural Hudson River school of thought that’s taking shape after decades of gestation. More important, these loosely excerpted chapters should inspire you to hit the road, witness the incredible transformation of a region, and consider taking part in its cultural renaissance.

LM Guest House

When young parents approached Desai Chia Architecture to realize a sustainable guesthouse on a 360-acre working farm in Dutchess County, they cited Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House among their inspirations. And at first glance, the New York–based studio’s response, called LM Guest House, appears to have more in common with the Mies masterpiece than not. Both rectilinear buildings approximate two thousand square feet, perch daintily on their lots, overlook bodies of water, and contain asymmetrically arranged spaces that support kitchens and bathrooms.

An exterior view into the living room of the LM Guest House in Dutchess County. Paul Warchol Photo.

Yet scrutiny reveals that Desai Chia adapted precedent, particularly by enlarging the core to accommodate a family of four plus two guests. LM Guest House contains two sleeping areas filled with bunk beds, a pair of storage spaces, and a mechanical room alongside bathing functions. Desai and Chia collaborated with engineers at Arup to embed four steel columns within the core that support a cantilevered roof, too. The facade comprises triplepane glass units to withstand the sun’s rays as well as extreme hot and cold, though breezes flow through operable windows. The results commune with nature so comfortably that the homeowners have deferred renovating a salvaged barn on the property as their main residence.

Architect Desai Chia’s LM Guest house emits a lantern-like glow after dark. Paul Warchol Photo.

Natori Residence

The Natori Residence one of several commissions that Brooklyn-based Tsao & McKown Architects has completed for fashion designer Josie Natori and her husband, Ken, over more than two decades. “We have come to know their habits and their aspirations,” says Calvin Tsao. For this latest home in Pound Ridge, “We got a sense they wanted to spend more time together even as they were doing different things.”

At the Natori Residence in Pound Ridge, designed by Calvin Tsao and Zack McKown, the garden’s water element forms a threshold to the formal entry. Simon Upton Photo

The single-story volume is constructed of visibly joined timber measuring five bays long by two bays wide, which minimizes walls within the 2,900-square-foot interior. The resulting space is modulated into zones, most notably in the living and dining areas, by two large standing-seam copper skylights. A custom bronze chimney and granite hearth further distinguish the living area without visually separating occupants from one another.

Skylights impart a memorable roofscape to the project and shape the experience within. Simon Upton Photo

These and other gestures also preserve views through expanses of glass to the thirty-acre site. To foster a relationship with the landscape, the architects ran a timber-columned veranda along the east side of the living and dining areas, created a terrace off the master suite, and wrapped a traditional Japanese garden around the west elevation. Tsao explains that these gestures “start conversations about the built environment and the natural environment.”

The architecture subtly demarcates different spaces within the living area. Simon Upton Photo

House 432

The southeastern edge of the Hudson valley defies clear definition. Where New York and Connecticut meet, the terrain varies between ridges and bowls, and is covered alternately in woods and meadows. One town’s primary intersection resembles a New England square while another’s is marked only by the crisscrossing of stone walls. Revolutionary-era shingled and clapboard houses huddle along the roads; bedroom communities loom over them from once-unbuildable prospects.

In House 432 the living room and dining room are connected, allowing for an integrated lounging and dining experience. Paul Warchol Photo.

Robert Siegel revels in these juxtapositions. House 432, a 3,600-square-foot Katonah residence that he designed for himself, his wife Lynn, and their three children, assimilates local knottiness into a deceptively simple diagram. Or as the architect puts it, “How do you design a home that looks unique, but not out of place—how do you understand context without being a slave to it?”

Architect Robert Siegel employed a variety of secondary structures to guide occupants and visitors toward the entry. Paul Warchol Photo.

The hilltop building maximizes distance from the road, prioritizing site over intervention. Building plan and section privilege the landscape as well: Siegel gave the house a slight boomerang shape to keep it from visually dominating the hill, and used few, albeit very large, windows to make the building mass seem smaller. Meanwhile, the crisply geometric house is clad in locally sourced fieldstone— it is both a naturalistic cloak and a fun nod to the region’s historical farm boundaries. The overall effect of the design is seclusion without parochialism.

Hidden enclaves such as a rooftop courtyard encourage family interaction. Paul Warchol Photo.

Ex of In House

Renowned architect Steven Holl had not intended to erect Ex of In House. But when the longtime weekend resident of Rhinebeck, New York, heard that a neighbor was advertising his twenty-eight-acre property as a subdivision, the prospect of suburbanization rankled him. He bought the property and determined to turn some ongoing research into a built form.

Architect Steven Holl initiated Ex of In House in Rhinebeck, New York, to prevent the underlying acreage from becoming a subdivision. Paul Warchol Photo.

Sleeping areas are hidden out of direct sight on the second floor. Paul Warchol Photo.

Holl had been figuring how intersecting spheres would look and feel as habitable space, and for Ex of In House he arranged slanted volumes and circular and wedge-shaped windows to ingratiate the built environment with the sun. Glazing on the south elevation is proportioned to heat the interior by thermal gain in winter, and glass flooring meets a dramatic window on the southwest corner so that sunsets are experienced without interruption. A geothermal heating system, super-insulated envelope, thin-film photovoltaics, and other active sustainability efforts reduce the house to almost net-zero consumption. Perhaps the boundary-pushing interior evidences an environmental ethic most of all. Holl’s shifting planes and kissing orbs create an interior landscape that contains only one door, and feels much larger than 918 square feet. The compactness is an inherently ecological gesture, and something of a political statement: The wide-open layout also expresses faith that guests can tolerate or even thrive in a world that lacks borders.

A view toward the entrance from the adjacent sitting area. Paul Warchol Photo.

The River House

The concept of “keeping up with the Joneses” may have been born in the Rhinebeck vicinity when, in 1853, Elizabeth Schermerhorn Jones’s soaring estate Wyndclyffe prompted a spate of mansion building and rebuilding all along the Hudson River. The home created by architect Steve Mensch for himself and Greg Patnaude now occupies the former great lawn of Wyndclyffe, which was abandoned in 1950 and today stands in ruins. Known as the River House, the five-thousand-square-foot building embodies present-day values in much the same way as the original Wyndclyffe captured its own time. The new house is horizontal, in contrast to the old building’s verticality. And Mensch’s design substitutes status with authenticity.

The aerie quality of architect Steve Mensch’s River House in Rhinebeck becomes palpable upon entering the living room, the glass walls of which are retractable. John Halpern Photos

Mensch envisioned the approach to the house as a slow, even mysterious, procession.The curved driveway is enclosed by high hedges and mature trees, creating a passage to a circular motor court encircled by woods, newly planted spruce trees, and the board-formed concrete walls of the house itself. These massive, windowless walls could very well be mistaken for ruins were it not for the delicate rooftop photovoltaic array signaling life and optimism.

The living room also overlooks a dramatic hillside to the south. John Halpern Photos

A covered walkway steers guests to the lone door and the petite, lowceilinged foyer, where a jog to the left leads to a fully glazed living room. Over the course of just a few steps, the hint of a bird’s-eye Hudson River view transforms into flight itself, and sunlight filters through the photovoltaics to produce dappled shadows. “Invariably, when newcomers come through that opening, they gasp, or exclaim, or sometimes just laugh,” Mensch says.