The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives

Exhibition

Happy Sesquicentennial, Frank Lloyd Wright

THIS SUMMER TWO MUSEUM EXHIBITIONS embrace the opportunity of the 150th birthday of Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959) to revisit his prolific career and design philosophy. One, at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), takes a wide-angle view of his career, and the other, at the Milwaukee Art Museum, goes narrow, looking in depth at the formation and evolution of his Prairie style. Both exhibitions offer new insights and never-before-seen works, providing even the most dedicated Wright fans and scholars fresh interpretations of the work of arguably the most famous American architect of the last century and a half.

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

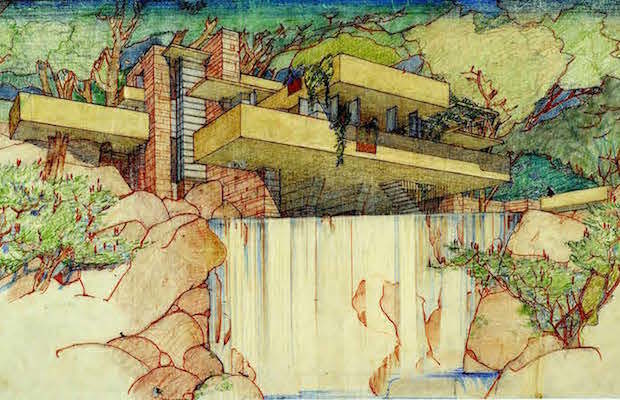

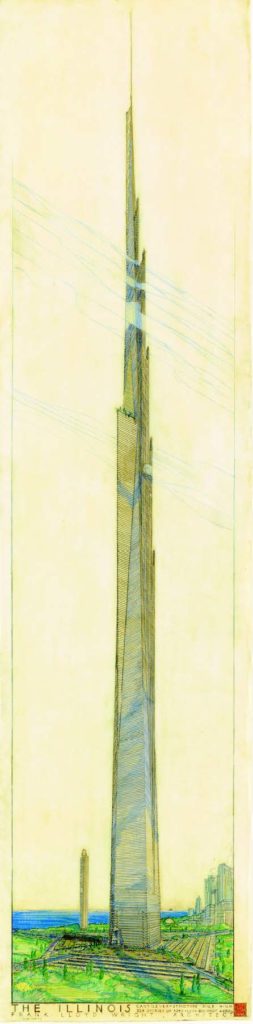

First, MoMA tackles the full scope of Wright’s career with Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive, on view from June 12 to October 1. Approximately 450 works dating from the 1890s through the 1950s—some of them never publicly exhibited before—are organized chronologically around the architect’s key designs, with twelve subsections delving into Wright’s fascination with Native American design, his ideas about American architecture of the future, and his preoccupation with ornament, to name just a few. Organized by Barry Bergdoll, a senior curator in MoMA’s department of architecture and design, and Jennifer Gray, a research assistant at MoMA, the exhibition defies the viewer to see Wright as solely a regional architect. Bergdoll and Gray include works from Wright’s thousand-plus global projects at all scales, from skyscrapers to landscape designs to light fixtures.

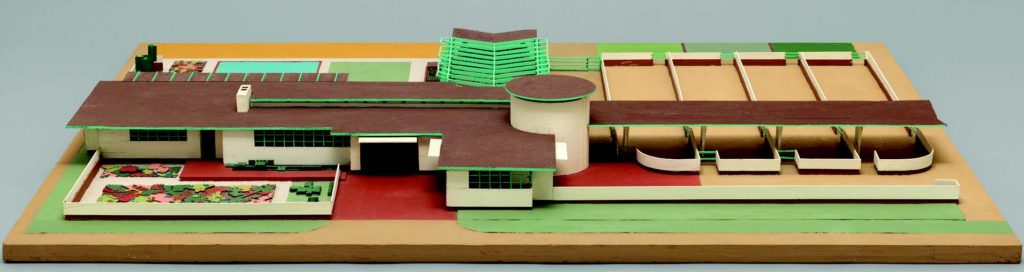

From July 28 through October 15, the Milwaukee Art Museum (MAM) homes in on a specific period of the Wisconsin native’s designs with Frank Lloyd Wright: Buildings for the Prairie. Focused on the architect’s early years, from the late nineteenth century to around 1910, the exhibition includes furniture, stained glass, textiles, and drawings that exemplify his development of a new architectural language. The Prairie house style used horizontal volumes and T-shaped plans to mimic the flat plains of the Midwest, where Wright had many progressive middle-class clients. The exhibition will showcase some of these iconic residential designs, such as the Avery Coonley House, the Darwin D. Martin House Complex, and Wright’s own Oak Park, Illinois, studio and home.

Most exciting is the chance to see a 1910 Wasmuth Portfolio, a boxed set of lithographs covering Wright’s most important commissions up to that point. It was an unusual marketing tool for its time, broadcasting the architect’s work and the Prairie school’s direction and principles. Published in both English and German editions in Berlin by Ernst Wasmuth, and encased in a Wright-designed box, the portfolio was a luxury publication, of which intact versions are very rare.

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

“The delicacy and beauty of it is absolutely thrilling,” says Brandon Ruud, a curator of American art at MAM. In addition to showing about three dozen prints from the portfolio, the exhibition will include a complete digitized version, allowing visitors to zoom in on particular details. “It’s a wonderful glimpse into the early part of Wright’s career and his formation as an architect,” Ruud says. The portfolio—as well as Wright’s travels in Europe around the time of its publication—increased his international reputation and his influence on early modernist architects such as Le Corbusier and Rudolf Schindler. (Tackling another specific period of Wright’s career this summer is Yale University’s publication of The Guggenheim: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Iconoclastic Masterpiece by Francesco Dal Co, which narrates the progress of that arduous seventeen-year project.)

Wright’s vast archives were permanently transferred from the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation to MoMA and Columbia University’s Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library in 2012, and MoMA’s exhibition—as well as another opening in September at Columbia (Living in America: Frank Lloyd Wright, Harlem and Modern Housing, September 8–December 17)—provide opportunities to unearth new connections and themes within the architect’s work. Unpacking the Archive asserts that Wright was perhaps the first celebrity architect, using the media and his own dissemination tools—like the Wasmuth Portfolio—to cleverly spread his utopian visions. MoMA’s and MAM’s exhibitions are all the richer for his foresight.

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)