CORNING MUSEUM OF GLASS, CORNING, NEW YORK/PHOTO COURTESY OF THE CORNING MUSEUM OF GLASS

CORNING MUSEUM OF GLASS, CORNING, NEW YORK/PHOTO COURTESY OF THE CORNING MUSEUM OF GLASS

Feature

Glass Rocks

Linda MacNeil is not the typical jeweler. MacNeil, who works without maintaining academic affiliations, has inserted her own voice into contemporary American jewelry as an innovator transforming glass into proxies for precious gemstones. A pioneer over her forty-and-counting-year career, this New England native has selected the necklace as her primary form. Uniting glass—hot-worked, industrially fabricated, cast, or slumped— which is then polished and/or acid-polished, with hand-manipulated metal stock and, more recently, with precious gems, she explores materiality and methodology. She uses historical precedent as a jumping-off point to make wearable statements that unite a powerful palette with softened geometric and organic forms. MacNeil’s visually exquisite and technically sophisticated work straddles two worlds—studio glass and studio jewelry. It is about adornment rather than narrative. In fact, MacNeil is not definitively identified with art jewelry because she emphasizes craftsmanship rather than content. Similarly, her work does not fit well contextually alongside nonfunctional glass sculpture. Nonetheless, MacNeil has overcome these obstacles of categorization to find her place as a significant contributor to decorative arts and crafts in the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries. The article that follows is adapted from an essay in the catalogue accompanying the exhibition Linda MacNeil: Jewels of Glass, on view at the Museum of Glass in Tacoma through October 1.

— Davira S. Taragin

AS A LEADING FIGURE IN CONTEMPORARY ART JEWELRY, Linda MacNeil has broken new ground, drawing upon centuries, if not millennia, of jewelry history while absorbing current trends in the fine arts, architecture, and design. Mining and reinterpreting historical styles and transforming them with her new and unique perspective, MacNeil personifies the postmodernist sensibility. The freedom either to accept or defy convention is inherent in her approach to jewelry design and fabrication. The distinguishing characteristics of MacNeil’s jewelry are its predominantly nonobjective aesthetic and its masterful integration of glass and metal into refined compositions that balance line, color, and light. Her necklaces and brooches are meant to be worn and are complete only when they complement and enhance the body.

MacNeil attended three of America’s leading jewelry programs in the 1970s, where she was introduced to the great diversity of approaches and techniques that jewelry artists were exploring. At the Philadelphia College of Art, the Massachusetts College of Art, and the Rhode Island School of Design, the modernist idioms of the 1940s and 1950s were being replaced with bold and often controversial social and political statements in response to the turbulent and dramatic events of the 1960s and 1970s: John F. Kennedy’s assassination, the civil rights movement, the Vietnam War, terrorism at the Munich Olympics, and Watergate. To incorporate this narrative content, artists commonly de-emphasized virtuoso metalworking techniques and used found objects and assemblage methods to create what effectively became small canvases that would carry their viewpoints into the world. However, the processes they used were not aligned with MacNeil’s more formal and structural approach, nor did she seek to create jewelry that carried strong political or social messages.

Sublime, no. 80 from the Brooch series, 2007–2013. Plate glass, mirror, and 18-karat yellow gold. COURTESY OF THE ARTIST/PHOTO © BILL TRUSLOW PHOTOGRAPHY

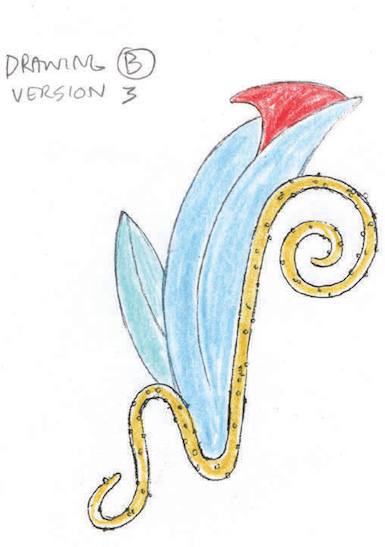

Sublime: Drawing B Version 3, 2007–2013. Photocopy with pencil and colored pencil. LINDA MACNEIL ARCHIVES, NEW HAMPSHIRE/PHOTO COURTESY OF THE ARTIST

Artists whose abstract works focused on materials and techniques were more in line with MacNeil’s thinking, and, in that regard, the 1970s offered her plenty of food for thought. She acknowledges the influences of Stanley Lechtzin (United States, born 1936), whose reinvention of the nineteenth-century electro-forming process allowed him to make large, fantastic brooches and neck collars; Arline Fisch (United States, born 1931), whose application of intricate textile weaving and knitting techniques to metal created decorative and body-flattering wearable ornaments; Albert Paley (United States, born 1944), whose dramatic, forged metalwork produced baroque sculptural pendants and brooches; and Marjorie Schick (United States, born 1941), whose boldly painted wooden brooches, referred to as “drawings to wear,” as well as her outsize collars and bracelets, affirmed jewelry’s role as sculpture and art. At this relatively early stage in her development, MacNeil had already begun to see a clear path amidst the polyphony of styles and ideas that surrounded her. She began expressing herself as a metalsmith and jeweler, taking a craftsmanly, decorative approach to creating jewelry intended to harmonize with and enhance the appearance of the wearer—jewelry that might be viewed as a reaction to the content-driven, perhaps less flattering, message-laden jewelry of the era.

The decisive event that established MacNeil’s unique identity as a jewelry artist specializing in glass was her relationship with the renowned glass artist Dan Dailey (United States, born 1947), first as her teacher at the Massachusetts College of Art in Boston in 1974, where he introduced her to the glass medium, and then, two years later, as her life partner when they moved in together. By the 1970s, studio glass—to a greater extent than studio jewelry— had captured a knowledgeable and devoted following, and Dailey had branched off from the mainstream and achieved widespread recognition for unconventional yet elegant glass sculptures that incorporated metal and showcased his masterful glassmaking skills. Intrigued by glass’s enormous potential for artistic expression, MacNeil widened her own focus and began working in the two media.

Necklace No. 26 from the Elements series by Linda MacNeil, 1984. Cast glass, Vitrolite glass, and 14-karat yellow gold. LOS ANGELES COUNTY MUSEUM OF ART, GIFT OF LOIS AND BOB BOARDMAN/ PHOTO © MUSEUM ASSOCIATES

While completing her studies at RISD between 1974 and 1976, MacNeil was immersed in a stimulating environment in which some of the most renowned glass artists and jewelers of the time interacted with students to challenge and expand their technical and artistic boundaries. She took an independent study class with the famed American glass artist Dale Chihuly (United States, born 1941) and was exposed to the latest approaches to glass and jewelry, primarily through John (Jack) Prip (United States, 1922–2009), her primary teacher and critic at RISD. MacNeil continued steadfastly to perfect her own aesthetic even after she left RISD and acknowledges the influence that many renowned American and European jewelers have had on her development, including Max Fröhlich (Switzerland, 1908–1997), for his simplicity and craftsmanship; Claus Bury (Germany, born 1946), for his graphics and use of acrylics; Wendy Ramshaw (United Kingdom, born 1939), for her use of the lathe; David Watkins (United Kingdom, born 1940), for his design of rigid forms; Lechtzin, for the working mechanics of his neck collars; Prip, for the ways to soften geometry; and Louis Mueller (United States, born 1943), for general design principles.

By focusing on glass as her principal jewelry component, MacNeil has added her name to a history that extends back more than five thousand years to man-made glass beads from eastern Mesopotamia. This long history notwithstanding, with few excep- tions, such as in ancient Egypt, where glass was rare and valued as highly as precious stones or gold, or in Venice, where glass beads served for centuries as highly prized export articles, glass carried little value save for its ability to imitate gemstones. In fact, glass was often selected with the intention of deceiving the buyer—a practice attested to by the Roman scholar Pliny the Elder (ad 23–79), who warned his contemporaries to be on the alert for counterfeit gemstones made of glass. In medieval Europe, the production and sale of imitation glass gemstones was strictly forbidden, with violations punishable by loss of the right hand and banishment. As glass-making technology advanced, new possibilities for subterfuge were presented, most prominently in the eighteenth-century French court of Louis XV, when the sparkle of paste glass with the addition of lead glass surpassed that of real diamonds.

Since the 1970s, when MacNeil set out on her career, art jewelry has become increasingly “global,” with ideas about design and fabrication traveling rapidly from one part of the world to another and from one culture to another. The debate concerning the use of precious versus non-precious materials is by now irrelevant, as gold and gemstones commonly appear alongside less costly materials, a practice of combining the “High and the Low” that MacNeil adopted early in her career. The desire to stand out in an increasingly crowded art jewelry field is often the driving force for emerging artists for whom nothing is taboo. MacNeil, by contrast, shuns superficial, “flashy” effects as her work continues to evolve and her curiosity and explorations steadily expand. Through impeccable craftsmanship and a sure eye for design, she has set a standard that has elevated the field and widened its appeal. Her elegant creations endure as objects of beauty and desire that are uniquely and unmistakably her own.

The opening of this article is adapted from Guest Curator Davira S. Taragin’s lead essay, “Linda MacNeil: Defying Categorization?,” in the catalogue accompanying the exhibition Linda MacNeil: Jewels of Glass, on view at the Museum of Glass in Tacoma, Washington, through October 1. The main text is adapted from the catalogue’s second essay, “Unmistakably MacNeil,” by Ursula Ilse-Neuman, Jewelry Curator Emerita at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York. The book is co-published by the Museum of Glass in Tacoma and Arnoldsche Art Publishers, Stuttgart, 2017.

Ram’s Horn, no. 42 from the Brooch series, 2005. Lead crystal, plate glass, and 18-karat yellow gold. PHILADELPHIA MUSEUM OF ART, PURCHASED WITH FUNDS CONTRIBUTED BY THE WOMEN’S COLLECTION OF DIANE AND MARC GRAINER/PHOTO © BILL TRUSLOW PHOTOGRAPHY

You may also like...

E-NEWSLETTER

Advertisement

Advertisement

MODERN Magazine takes a fresh and intelligent approach as it examines buildings and interiors, furniture and objects, craft and art—delving into the creative process and offering sage advice for both the seasoned and novice collector or connoisseur.

© 2019 MODERN Magazine Media, LLC

LATEST NEWS

-

DAVID SOKOL | April 29, 2019

DAVID SOKOL | April 29, 2019Method & Concept Shakes Up the Design Scene in Naples

Chad Jensen opened Method & Concept in Naples, Florida, in 2013 according to the Art Basel Miami Beach...

-

ADRIAN MADLENER | April 24, 2019

ADRIAN MADLENER | April 24, 2019Collectible Milan

The annual Milan Design Week has long been the established benchmark of the industry. Comprised of the massive...

-

JUDITH GURA | April 22, 2019

JUDITH GURA | April 22, 2019Breakout Efforts at the Corning Museum of Glass

Those who don’t consider glass a major art medium will think again after visiting a fascinating exhibition that...

-

ANNA K. TALLEY | April 18, 2019

ANNA K. TALLEY | April 18, 2019Designers Envision the Future of Water at A/D/O

For Jane Withers, the London-based curator and writer who led Water Futures, design incubator A/D/O’s latest initiative, this...

-

MATTHEW KENNEDY | April 18, 2019

MATTHEW KENNEDY | April 18, 2019Delving Deeper

Why an uncharacteristically meditative Memphis design mesmerized one resourceful bidder

-

EZRA SHALES | April 16, 2019

EZRA SHALES | April 16, 2019Design Destination: Stockholm

TO STROLL ALONG STOCKHOLM’S HARBORS is to inhale the essentials of the city’s largesse and welcoming grandeur: the...