Feature

Garden Angels

The abstract shape of the pool plays to the trapezoidal terraces and contrasts with the vertical lines of the pines beyond the redwood benches. As James Rose advised, a landscape is a living thing so it requires intuitive maintenance, not just preservation. The Yarbroughs have been actively engaged in such intuitive maintenance for many years, including having to replace plantings as well as the crossties of the terraces and the redwood benches.

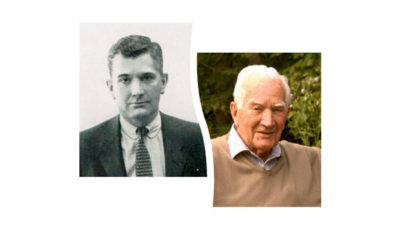

If you were to devise a manual for how homeowners should value a classic modern landscape and, through love and understanding, maintain it over time—and even nurture its growth and changes as the designer would have wanted—it would look a lot like this story. Designed by preeminent American landscape architect James Rose of Ridgewood, New Jersey, in 1959 and now owned by Sidney H. Yarbrough III, M.D. and his wife Becky in Columbus, Georgia, the garden had the good fortune to fall into the right hands thirty-eight years ago, and is now among the best-preserved, if not the very best, Rose garden that still exists. A contemporary of Dan Kiley and Garrett Eckbo, Rose devoted his career (beginning in the 1940s) to designing private gardens in the modernist genre. His work continues to have a profound impact on modern theory and practice.

“My wife and I moved back to Columbus in 1970, where we were both born and raised, after I completed my training as an orthopedic surgeon at Emory University,” Sid says. “Within a year, we were invited to a party at the home of Cliff Averett, which he hosted for the purpose of selling real estate in the Bay Point development in Panama City, Florida. We didn’t buy any property in Bay Point, but we did notice how unique and special Cliff’s house and garden were.”Point, but we did notice how unique Cliff’s house and garden were.”

The Yarbroughs established themselves in Columbus and took an interest in art and design, deciding early on that they “didn’t want to live in a house filled with things you buy from the store.” Sidney, whose “gun was loaded” by an art class he had taken in school, wanted to collect art—particularly decorative artifacts, which he felt had more historical resonance than the objects at Bed Bath and Beyond. Busy at work, he didn’t have an enormous amount of free time, but he joined Becky on visits to museums and galleries whenever he could. Becky soon joined the board of the Columbus Museum of Art, where she has continued to serve for more than thirty years.

Through friends the Yarbroughs had been introduced to the idea of a modern house with enormous glass walls and high ceilings. By 1974 they had three young sons and were ready to settle into a family home. Averett’s house was for sale, and they wanted it. “I said, ‘Cliff, we’ll buy the house. We just need to agree on a price,’” Sid says. Within months, the deal was done.

When he designed the house in 1959, local architect Rozier Dedwylder essentially dropped it in the middle of the woods. Thick natural growths of long- and short-needle pines and oak trees envelop the lot. Consistent with the modernist movement that rebelled against the formal Beaux-Arts tradition, Dedwylder and Rose collaborated to connect the indoors and outdoors. The floor-to-ceiling windows look out on a distinctive, geometric garden that still seems progressive. It is comprised of trapezoidal terraces demarcated by railroad crossties, leading down to an abstract geometric pool and out to the woods beyond.

From the very start, there was an innate willingness on the part of the Yarbroughs to engage the landscape as stewards. They kept up the redwood benches, crossties, asphalt, and plantings as if they were carrying out the designer’s maintenance program. Five years into owning the property, a good friend gave them a copy of the book Modern American Gardens Designed by James Rose by Marc Snow. To their surprise, they discovered their own garden in its pages. Anticipating that his works would be at risk as the decades passed, Rose (Marc Snow was his pen name) had written: “The question of what happens to landscapes in ten years or more is often raised. The answer is they change. They change enormously with plant growth, with the change of attitudes and ideas of the people who live in them.” Happily, in the Yarbroughs one of his works had found wise protectors.

“A pool contractor came to us with a proposal for completely redoing the pool deck. He meant well, but he was too quick to recommend that we take out the pool and start from scratch with one that had all the contemporary amenities. I balked at it. Somehow I knew it wasn’t right,” Sid says. Instead, roots and rain have tilted sections of the pool deck slightly, but unless the hardscape “falls into the water,” they will leave the pool alone, save for fixing the filtration system.

Their approach to the garden vacillates between leaving it to its own devices and getting very involved. “I never imagined I’d become an expert in crossties,” Sid says, “but I’ve replaced them four or five times myself. I figured, I have a strong back. I can do it. When the crossties are stacked, they last thirty years. When two sides touch the earth at the edge of a terrace, they only last ten. And a chainsaw can only cut through a crosstie ten times before it dulls.” “As an orthopedic surgeon,” Becky adds, “Sid has always had a feeling for putting things together. So when he undertook the crossties, I knew they would be done correctly.”

The difference between pure preservation and stewardship arises when nature takes over. Two hard freezes in the late 1970s killed a small orchard of loquat trees in the courtyard area, so Sid harvested some cedars from his adjacent farm and planted them as replacements. Recently, he had the cedars removed because they had grown so enormous, a lesson in choosing the right plantings. He’s now looking for something suitable to fit the landscape and stay small.

But the rewards are great. One morning in 2009, after a snowfall the night before, Sid and Becky looked out their windows. The snow had melted on the asphalt, but remained on the crossties, brilliantly revealing anew the bones of their garden. “The snow on the crossties made a beautiful mosaic,” says Becky. “I could feel the rhythm that Rose must have had as he planned the way he put the squares, rectangles, and triangles together with concrete, asphalt and crossties.” It was one of thousands of moments when it was clear that preserving their garden, and letting it evolve only in neccesary ways, brought them immense satisfaction.

The details of maintaining their landscape that are so compelling to the Yarbroughs would be overwhelming to most people. Last year the Yarbroughs were recognized for their work with a Landslide designation from the Cultural Landscape Foundation, an organization that raises awareness about threatened landscapes. Through associated education seminars, ongoing internet publicity, and fundraising, this designation will help ensure the longevity of the garden, in the same way that it has helped save important national treasures like the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden; the Becker Estate in Highland Park, Illinois; and Park Central Square in Springfield, Missouri.