Feature

FROZEN MUSIC

The powerful photography of Héléne Binet

Firminy – C (architecture by Le Corbusier), 2007. Silver gelatin print.

WHEN HÉLÉNE BINET TALKS about photography, she speaks reverently and a bit gently. “I often compare myself to a musician with a score,” she says. “I can do my own interpretation, but I have to respect the notes and the score, respect the music.” In Binet’s case, the music would most likely be Gustav Mahler—achingly beautiful and soaringly powerful. Her photographs can be like that, too; they are full of dimension, depth, and contrast—using light and shadow and solid and void to draw us into a space, and then somehow they delve even deeper. “In my photography,” Binet says, “I ask what is the meaning, where is the soul?”

Often she uses details or fragments to tell a larger story. Her work is multilayered and profound. “She is not just photographing architectural subjects, she is exploring three dimensional volumes through light, shadow and texture,” says the gallerist Gabrielle Ammann, who has shown Binet’s work for the past eight years.

Chappelius 01, Valls Valley 2008. Silver gelatin print.

Binet began photographing the work of some of the world’s most interesting and innovative contemporary architects a quarter of a century ago. She has shot Zaha Hadid’s buildings since the beginning, starting with the Vitra Fire Station in Weil am Rhein, Germany and most recently the Dongdaemun Design Plaza in Seoul, South Korea. Her collaboration with the Swiss architect Peter Zumthor has been commemorated in books and exhibitions. The list of living architects whose work she’s explored includes Daniel Libeskind, David Chipperfield, Coop Himmelb(l)au, Studio Mumbai, Raoul Bunschoten, and Peter Eisenman. Often she follows a project from the start of construction until completion in order to dig into the process in what she calls “an intense and powerful” investigation.

002.tif

She has also documented important historic architecture, ranging from a photographic essay on the churches of Nicholas Hawksmoor, who worked in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, to studies of Alvar Aalto and Le Corbusier, whom she terms “the great master.” Photography of historic buildings is what propelled her career at the start, and she continues with historic subjects today. “For me,” Binet says, “it is very important, that stepping back and looking at why a building is what it is. There’s a physical patina of time that allows the camera to play at many levels.”

La Tourette – skylights (architecture by Le Corbusier), 2007. Digital c-print.

In the last decade or so Binet also has begun to photograph the natural landscape, producing work that exults in the wonder of a tangle of tree branches or probes the mystery of a geological formation. Her approach to nature is much as it is to architecture. Though the images show us concrete (sometimes literally, as well as figuratively) buildings and real places, there is always a level of inscrutability to them. “I hope my photographs, which are quite abstract, allow the person who is viewing them to have his or her own thoughts,” she says.

Ammann, who both trained and practiced interior architecture early in her career, first encountered Binet’s work in 2007 while mounting an exhibition devoted to Hadid at her eponymous Cologne gallery. Looking at the photos Hadid had supplied, Ammann found herself transfixed by their power. Two years later she mounted her first Héléne Binet exhibition, showing the work of Zumthor, and she has represented Binet ever since. “She transcends representation and captures the essence of the experience of the space and the spirit of her subjects—whether it is an eighteenth century church by Hawksmoor or a museum by Hadid or a spa by Zumthor,” Ammann says.

Bruder Klaus Field Chapel (architecture by Zumthor), 2007. Silver gelatin print.

Binet’s work has been exhibited around the world, including at the 2012 Venice Biennale and most recently in Los Angeles, where in February she received the prestigious Julius Shulman Prize for photography from Woodbury University. An exhibition of her work at the university’s WUHO Gallery in Hollywood runs through March.

The daughter of musicians, Binet grew up in Rome, and when she opted to study photography, she thought her path would lead her to the great opera houses and theaters of Europe. Instead, she found herself drawn to architecture, to the opportunity to ask larger questions: What is space? How do you feel space? How do you perceive it? “I wanted to show that photography can be very emotional, not hard,” she says. “I wanted to bring dimension into something that is flat.”

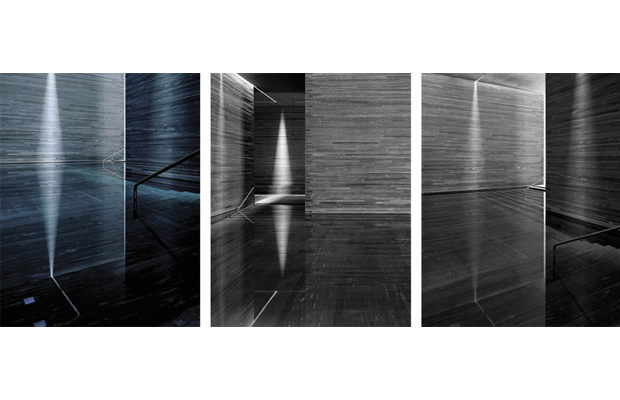

Therme Vals Triptych (architecture by Zumthor), 2006. Digital c-print and silver gelatin prints.

She moved to London about thirty years ago at a time when architecture was just starting to change. She began working with Alvin Boyarsky, then director of the Architectural Association School of Architecture, to produce books, largely on historical architectural subjects. At the Architectural Association she also met such then unknown architects as Hadid and Libeskind, both in the early years of their careers. She has followed both over the years, and she says that such relationships have allowed her to “collaborate in an inspiring and beautiful way, enhanced by an intense understanding of the process.”

Hadid admires Binet’s work for its “striking balance between light and shadow, matter and void, rawness and strength” and singles out the photographs Binet shoots during the building process. “I very much like the photos Héléne takes of my buildings during construction; she is always able to capture the essence of any project, translating it into sharp, abstract, powerful images.”

Jewish Museum (architecture by Daniel Libeskind), 1998. Silver gelatin print.

A few years into her career, Binet encountered the work of Zumthor and was immediately captivated. Both Hadid and Zumthor are winners of the Pritzker Prize in Architecture.

Importantly, Binet prefers to work in black and white and often uses film rather than a digital camera. “For me,” she says, “limitation is more interesting. If you work with a digital camera, there is always the thought in the back of your mind that you can change the image. You lose that moment of frozen concentration.”

MAXXI Diptych (architecture by Hadid)

2009, silver gelatin prints.

Likewise, she still develops and prints her black-and-white photos. “I like to work with my hands,” she says. “I like the feel of film. I like to pick the paper.” The eye and the hand show: if the subjects are monumental, her photo- graphs nonetheless have an intimacy to them, an immediacy. “One can see and feel her deep understanding of the characteristics of each single building or detail she is portraying and that makes her and her works so unique and precious,” Ammann says.

Photos Courtesy of the Gabrielle Ammann Gallery