Design

From the Editor

Out of the Ordinary | Summer 2015

LIFE IS FULL OF LESSONS. One of my closest friends over the years was an art critic who could find something to admire almost everywhere she went. Her world was populated, of course, by beautiful paintings, but she could elevate so many other objects and things—a soup can, a wrapped present, thrift-shop tea towels, a pair of shoes—into works of art because she saw them for their design and for their possibilities. Others of us would have left the grocery store without that particular can of tomatoes because we hadn’t stopped long enough to admire its label. We would not have looked closely enough to see that what appeared to be plain brown wrapping paper actually had a faint microscopic pattern that came out once you added a ribbon. In my bathroom are three small hand towels she gave me that are, most likely, mid-century English (not sure because she pulled them out of a bin at a flea market).

I was thinking about that particular talent during the weeklong Salone del Mobile in Milan. It’s a week of exhaustion (too much to do, too much to see) and exhilaration. The latter comes with the opportunity to peek inside an exquisite privately held palazzo, as I did for a dinner hosted by Airbnb, or traipse through the back streets of the city to find a particular exhibition, as I did to see young London designer Max Lamb’s simple installation of some forty of his own chairs (some refined works in metal or stone, others purposely primitive, such as a carved-out tree trunk—but all quite engaging) set in a large circle in an otherwise unadorned former industrial garage now called Spazio Sanremo.

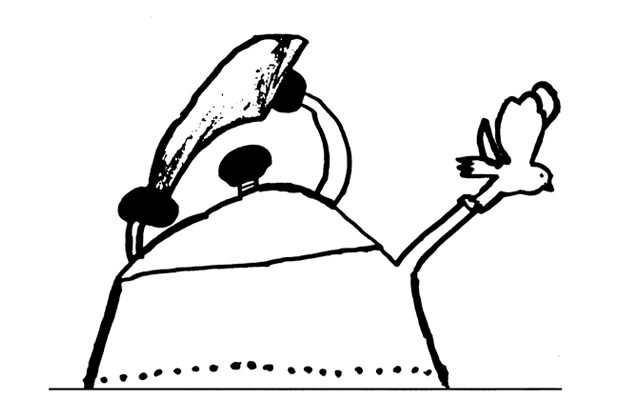

Late one afternoon in Milan, I had a brief talk with Alberto Alessi. We discussed just two of Alessi’s products—Michael Graves’s whistling teakettle with the bird on it and Philippe Starck’s Juicy Salif. No other objects are more emblematic of Alessi, and both were on my mind, the former because Graves had just died in March and the latter because it is now a quarter-century old. Alessi told me that the teakettle was actually painstakingly designed, with lots of back-and-forth sketching and conversation. The Juicy Salif, the hand juicer that stands on attenuated legs, was much the opposite: Alessi had asked Starck to design a tray (“who doesn’t need a tray?” he asked, almost rhetorically) and then waited. One Saturday morning he was in the office and a box arrived with the prototype Juicy Salif instead. It was almost perfect (Alessi made one change), and that morning it had the effect on Alessi that it has on all of us—it brightened his day. Different processes entirely, but in the end, both the kettle and the juicer offer us new ways to look at common objects.

Through this issue you’ll see stories that deal with that experience—the moment of encounter when the ordinary becomes extraordinary. It’s a lesson we should all learn, but more importantly, carry with us: it’s not enough to look, we also have to see.