Design

Flea Circuit

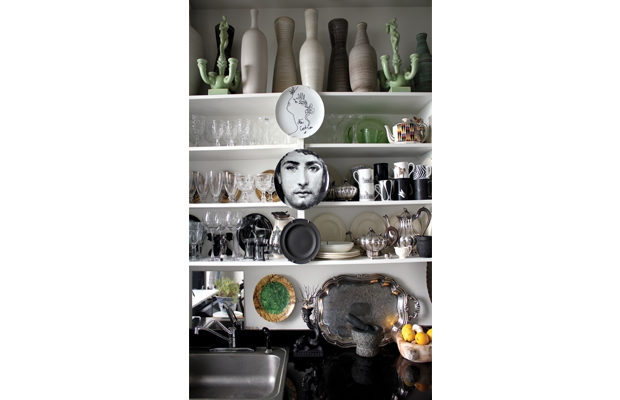

Gillette’s kitchen shelves are a virtual simulacrum of a flea market, holding such diverse items as a colorful Czechoslovakian art deco teapot, Italian ceramic candlesticks, Depression glass, an American silver tea and coffee service, and plates with designs by Jean Cocteau and Piero Fornasetti.

Flea Circuit:

New York artist and interior designer Richard Gillette reminisces about times of yore, when his happiest days were spent prowling the city’s design-maven’s mecca, the late Chelsea Flea Market

Some years back I received a phone call on a Sunday morning—this was when people still called one another: no text messages then—from a friend (who was also a client) checking to see if I was going to the Chelsea Flea Market. That was the common name for the sprawling area, centered on a block-long parking lot on Sixth Avenue between 25th and 26th Streets, which was surrounded by satellite fleas in garages and smaller lots. It was heaven for treasure hunters like me.

That Sunday in the 1990s the market was at its peak. Not only was it a great venue in which to find small objects, furniture, artwork of all types, clothing, and items that fell into some mysterious unnamed category, but also a place to see and be seen. The incongruous juxtapositions of goods could be confusing. On that day, after hours of taking a general overview of the inventory of countless vendors, I ran smack into the person who had phoned. Plans to hook up there rarely materialized with all the distractions. Cell phones would have helped. Some professional prospecting teams back then used walkie-talkies.

I was generally on a mission to find something to help round out an interior design project, but most people went to the flea market without an agenda and that was the fun of it. If I did become passionate about a find that I thought was perfect for a job, or was something I wanted for myself, having a mover or someone with a vehicle available at a moment’s notice was invaluable. Still, there were many times that saw me begging a cabbie to let me shove a table into his car. If worst came to worst, I’d drag things onto the subway.

The French term pêcheurs de lune, or fishermen for the moon, is a romantic way to describe some dealers. They sold what they could find. Week after week they would lay out questionable items, but once in a while a gem would materialize in the form of a tiger’s-eye ring or a Navajo basket. There were a few obsessive vendors, such as one fellow—a hoarder—who camped on 28th Street surrounded by a chaotic array of magazines, books, prints, photographs, and old suitcases. When he did agree to part with something, after the sale his regret was expressed so loudly you could hear his lament all the way to 29th Street. But more often than not the dealers were good-natured and had a clear idea that a Charles Eames chair, a Heywood-Wakefield night table, or a Greene and Greene cabinet were classic designs and their value would remain intact.

As an artist and interior designer my work is hard to pigeonhole. I identified with the outsider art dealers and the work of the creative people they sold. Drawings, silk screens, paintings, and sculptures that were totally unique or had cubist, expressionist, or figurative qualities were snatched up by collectors with vision. Now we have outsider art fairs worldwide.

A few of my friends made careers out of scouring the markets. They were known as “pickers” and had the ability to know the intrinsic value of something from experience, and, more importantly, because they possessed a keen eye. One specialized in clothing and if there was a 1920s beaded dress to be had, she was there to snatch it up. Another colleague knew a real Danish ceramic object from a poor man’s version. There were as many picking specialists as there were categories to pick.

I’ve had the pleasure of visiting flea markets and working on projects in France, England, Turkey, Spain, and many other locations around the globe. I took a moment to go through the pages of my book, The Art of the Interior, to try to remember where some of the key elements featured in the interiors had come from. Looking at photos of one of my earliest projects, which incorporates a series of 1940s wall sconces with plaster-framed mirrors, brought me back to the day when my contractor and I spotted the sconces lying on the asphalt of a Sixth Avenue parking lot. Salvaged architectural details discovered in markets—iron gates, wooden doors, stained glass, vintage sinks, tubs, glass door handles—turn up in so many of my designs. You name it and it can most likely be found. You just have to know where to look.

Invariably urban development encroaches on valuable real estate sites. This is what happened to the Chelsea flea: in 2006 a residential tower opened on the site of the main lot. Two years later the parking garage market on 25th Street, where the organizers behind the Chelsea flea had first set up shop in 1976, was shuttered.

Today it seems almost unnecessary to move from your computer screen, what with all of the websites that have replaced the markets, pickers, and open-air dealers. But by no means is the experience of the flea market dead. Several years in advance of the Chelsea flea’s demise, that market’s operators had the prescience to open a new flea, to the north and west of the old area, in Manhattan’s Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood. Before writing this piece, I called some friends to see if they would like to join me at the Hell’s Kitchen Flea Market. Surprisingly, they jumped at the chance, and the unique experience of the flea market—the fun, frustration, and elation—still worked its magic.