Donald Judd in 1990 at his former residence Eichholteren, a Swiss inn he remodeled. Courtesy Judd Foundation; © FBM Studio; image: Franziska & Bruno Mancia

Donald Judd in 1990 at his former residence Eichholteren, a Swiss inn he remodeled. Courtesy Judd Foundation; © FBM Studio; image: Franziska & Bruno Mancia

Exhibition

Domesticity by Design

IT COULD BE SAID THAT TWO EPISODES WERE CRITICAL in shaping artist Donald Judd’s approach to furniture design. The first was a false start: in 1968, having been asked to make a coffee table, Judd, by then well known for his iterative, minimal, and rigorous rectangular volumes, retrofitted an artwork, an experiment that corrupted the work and yielded a bad table. “Due to the inability of art to become furniture,” he wrote, “I didn’t try again for several years.”

Copper armchair designed by Judd in 1984, fabricated in 1998. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, gift of Byron R. Meyer. Photo by Katherine Du Tiel.

Judd’s next significant attempt came after he’d decamped with his kids and some art but little else from New York to Marfa, a small town in remote West Texas. When he set about cultivating “the necessary domesticity” in their new home, a two-story former quartermasters’ office, he found in Marfa’s few stores only bogus antiques and kitsch. Out of what he saw as necessity, Judd created his own furniture, beginning with a bed for his children. Made of pine one-by-twelves direct from the lumberyard and consisting of a large platform with a bisecting wall, it resembled a refined shipping pallet. “I liked the bed a great deal,” Judd wrote, and over some twenty years he produced a genus of desks and chairs, beds and benches, shelves, tables, and stools, in plywood, wood, and metal, that illustrated how little form is truly essential to function.

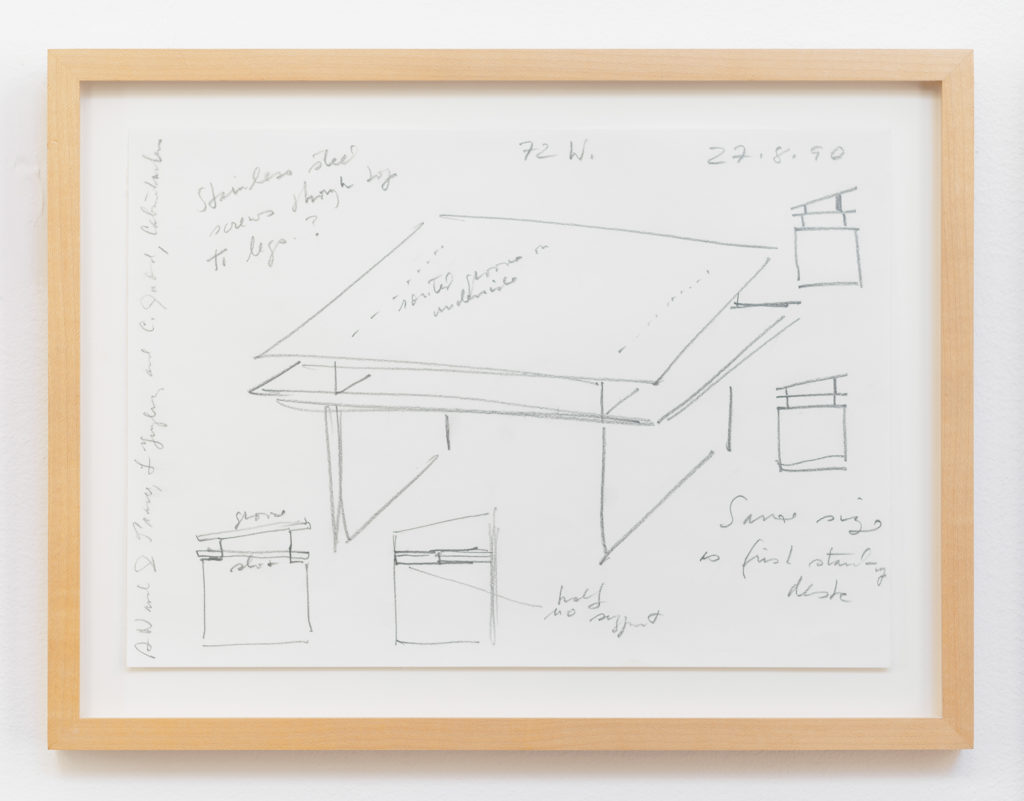

Sketch for a birch plywood standing writing desk, August 27, 1990.© Judd Foundation

An upcoming exhibition at SFMOMA, Donald Judd: Specific Furniture (July 14–November 4), considers Judd’s furniture design as a practice independent of his artistic production and, through sketches, photographs, and some thirty pieces spanning the 1970s to the early 1990s, it also affirms a distinct philosophy and guiding values. Punctuating the exhibition are examples of historical designs by Gustav Stickley, Alvar Aalto, Rudolph Schindler, Gerrit Rietveld, and Mies van der Rohe (whom Judd called “the last architect capable of elegance in a traditional sense”) that Judd admired and collected. “My interpretation is that he was surrounding himself with objects that he felt satisfied a certain set of criteria,” says curator Joseph Becker, “the same set of criteria that he held his own work against.”