Christo and Jeanne-Claude on-site at The Gates, Central Park, New York City, 2005. It was their last project together before Jeanne-Claude’s death in 2009.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude on-site at The Gates, Central Park, New York City, 2005. It was their last project together before Jeanne-Claude’s death in 2009.

Feature

Christo’s Next Chapter

ON A DRIZZLY AFTERNOON SOMEWHERE between winter and spring, Christo is thinking about summer. He is at his home in SoHo, in the cast-iron building he and his late wife, Jeanne-Claude, moved into in 1964. “Phil Glass installed our bidet,” he says, “and Gordon Matta-Clark put in the closet.” Much has happened since then: Christo and Jeanne-Claude completed twenty-two projects, all in the public eye and at an extraordinary scale. Over the years they have stacked, wrapped, covered, shrouded, and surrounded buildings, monuments, Roman walls, beaches, bridges, islands, trees, barrels, even bales of hay—and more. But today, Christo is looking forward as much as he is looking back.

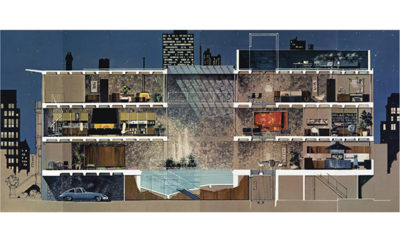

For the last two years, he’s been hard at work on the twenty-third project, to be open for a mere sixteen days, June 18 through July 3—a luminous, golden-hued floating walkway connecting the shore of the Alpine Italian Lago d’Iseo to the mountainous island that sits in the middle of it. The setting is stunning—a long, deep, narrow lake with dark blue-gray-green waters, ancient towns, and a landscape that is simultaneously lush and rugged. The project has—as is always the case with Christo—a simple, straightforward name that tells the basic story: The Floating Piers.

Jeanne-Claude died of a brain aneurysm in November 2009. She and Christo, both born on June 13, 1935, sometimes referred to themselves as “lunar twins,” almost as an explanation for the seamless connection between them. The couple—he Bulgarian by birth (his full name is Christo Vladimirov Javacheff) and she, French—met in Paris in 1958 and almost immediately began producing the work that would define them. Jeanne-Claude’s death came four years after the last project they would see to completion together, The Gates: a total of 7,503 saffron-orange free-flowing banners affixed at both sides to stanchions that marked a twenty-three-mile-long journey along the walkways of New York’s Central Park in the deep of winter, brilliant against a landscape that in the course of sixteen days went from bleak and dreary to sunny and crisp. “Jeanne-Claude always said ‘I’d love to have snow,’ and snow we got, some rain, but snow,” Christo says, almost as if in epitaph.

Some years passed. “By 2014 I said, ‘Look, I will be eighty years old soon, I need to see things happen.’” That is when Floating Piers was resurrected. Like many projects by Christo and Jeanne-Claude, this one has deep roots, going back to 1970 when they envisioned a two thousand-meter inflated pier in the gulf-like Río de la Plata in Buenos Aires, Argentina. That was never realized, but Christo and Jeanne-Claude loved the idea of a walkway in the water. Much later, in 1996, they sought to build fabric-covered piers leading from two artificial islands in Tokyo Bay to Odaiba Park. By then they had wrapped the Pont Neuf and a coastline in Sydney, Australia; covered a portion of the Newport, Rhode Island, oceanfront; and surrounded eleven small islands in Biscayne Bay with bright pink polypropylene, making them look like so many outsized water lilies. Still, one could only look at and not walk on Surrounded Islands. “But this was still one project that was nourished in our hearts,” Christo says.

Images of the lakes of northern Italy lingered in his mind. He gathered a crew that included Wolfgang Volz, the photographer who has documented a significant share of his and Jeanne-Claude’s work and who also functions as project manager for the Piers, his nephew and operations manager Vladimir Yavachev, and his registrar and curator Josy Kraft, and began to visit the lakes, systematically: Como, Garda, Maggiore. It was Iseo that captured their attention and became the site of Floating Piers.

Iseo is a deep lake, shaped like a scythe and nestled into its mountain setting, its dark water one of those colors that no one ever seems to put a name to. The lake, Christo says, was a principal departure point for the Roman army, and sketch maps dating to 1510 have been attributed to Leonardo da Vinci. As northern Italian lakes go, it is less famous and less glamorous, but it is set apart from the others by its 1,969-foot-tall mountain-island, Monte Isola.

Ordinarily, this island is only accessible by private boat or ferry. The fabric-covered walkways of Floating Piers are a color Christo selected—he calls it dahlia yellow—that changes throughout the day, chameleon-like. “In the morning it looks deep red, very beautiful,” Christo says. “When it’s wet, it’s reddish-orangish, but at midday, it’s a brilliant gold, almost pure gold.”

Technically speaking, the project involves two hundred thousand high-density polyethylene cubes (manufactured in a round-the-clock marathon in the nearby city of Brescia) pushed into place by tugboats, then connected to each other by some two hundred thousand screws, and secured by 140 cement anchors that weigh five tons each and were dropped into place by giant industrial balloons—an act that Christo calls “so poetic.” Beyond the engineering and manufacturing, every project also has life-size tests, “for aesthetical purposes,” Christo says. In the case of Floating Piers, a full-scale mock-up was floated into the Black Sea near Bulgaria.

All of this, put together with the more than seven hundred thousand square feet of fabric, will saturate (with color at least) the towns on either side of the floating walkway and connect them, allowing pedestrians to “literally walk on water,” Christo says, adding, “when you walk, you feel the water beneath you. It’s very sexy.” The fabric will start in Sulzano, cross to Monte Isola, wrap partway around the island, then cross the water again to a tiny privately owned island called San Paolo, touching down, and then crossing back again to Monte Isola.

Through September 18, the Museo di Santa Giulia in Brescia is showing an exhibition entitled Christo and Jeanne-Claude: Water Projects. Curated by Germano Celant, the show is at once dramatic and didactic (in the good sense of the word): using preparatory drawings, plans, collages, photos, film, and scale models, it clearly traces the trajectory of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s work—starting with the stacked oil barrels that closed the Rue Visconti in Paris for eight hours in 1962—and explores in detail the artists’ water-based projects.

The exhibition tells the fuller story of a Christo and Jeanne-Claude project—from the search for a site, to the detailed engineering drawings, to the political and environmental wrangling that leads to approval. Plans for The Gates started in 1979, and the still-to-be-realized Over the River (in Colorado) began its path to approval in 1992. Wrapped Reichstag took from 1971 to 1995. (By contrast, with an application from the British engineering firm—it contained just a single phrase saying “designed by the artist Christo”—The Floating Piers had a comparatively easy path.)

Each project yields as many as five hundred drawings, photographs, engineering plans, and other documents, along with, for a number of the bigger projects, a documentary film. From start to finish, the process is part of the art. As is the artist: “I love the physicality of the real thing,” Christo says. “I don’t know how to drive. I don’t like to talk on the phone. I don’t have the slightest idea about computers. I don’t even have a stool in my studio. Also I like to work with people, with humans.”

Still to come are Over the River, for which a shimmery pale permeable fabric will be hung over a forty-two-mile stretch of the Arkansas River, and The Mastaba in Abu Dhabi, in which Christo will stack 410,000 multicolored oil barrels into a flat-topped, slope-sided permanent sculpture (the artists’ only one). Christo and Jeanne-Claude first visited Abu Dhabi in 1979, but the stacked barrels go back to the Rue Visconti installation in 1962. Through November, an exhibition at the Maeght Foundation near Saint-Paul de Vence, France, features a three-thousand-barrel sculpture in the museum courtyard along with paintings, sculpture, photography, and scale models.

“Every project is a slice of our lives, an adventure,” Christo says. “Still today, alone and without her, I’m enjoying the journey because every project is so unique on every level.”