COURTESY BRUCE CAMPBELL

COURTESY BRUCE CAMPBELL

Design

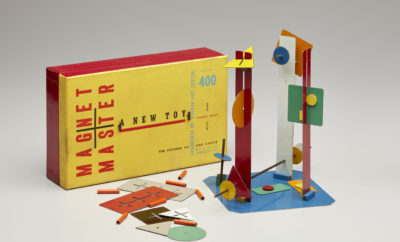

Bruce Campbell: Making Sculpture Kinetic

ONE OF BRUCE CAMPBELL’S FAVORITE POETS is E. E. Cummings, and the last line of Cummings’s poem “[anyone lived in a pretty how town]” reads: “sun moon stars rain.” This one line held particular appeal for Campbell and made him start thinking about how he could depict these things and conditions in his wirework, which until this time had primarily depicted animals and, through them, the concept of movement. He was not trying for scientific accuracy but wanted to portray these ideas through the mechanics, the movement, and the materials used in the work. Says Campbell: “How could I depict an eclipse, a meteor shower, or the orbit of the planets in a way that would engage the viewer?”

COURTESY BRUCE CAMPBELL

Campbell (born in Huntington, New York, in 1946) was the son of an electrical engineer who liked to build and fix things in his small garage workshop. He enjoyed working there with his father. He also says that he loved being outdoors, and “I loved working with my hands, spending time carving and chiseling wood, molding clay, and making small implements out of coat hanger wire, experimenting with the properties of metal when heated and hammered.”

As a child, Campbell says, he was always curious to know how things were made and was constantly taking things apart to see how they functioned. He worked with old tools and found objects, salvaged from the past. “I had some old license plates from the 1920s and found that the metal was heavier than that used today,“ he says. “When the rust is removed and they are heated flat, the patina is quite beautiful. I also loved the fact that these plates had a former life and identity.” He feels the same way about his sculpture bases, preferring old wood to new.

Campbell does not use motors, allowing observers to crank his kinetic pieces at a speed that allows them to engage them personally, rather than watching a motorized piece move at a predetermined, repetitive pace. “When I have a show I get particular pleasure watching people turn the crank of my kinetic sculptures,” he says. “Everyone does it differently and it is fun seeing them try to figure out why a certain piece is moving. This is why I do not want motors to power the works.”

“There is an inherent beauty in everything. Look what Joseph Cornell did with discarded items he found along the road.” This attitude was encouraged at Blair Academy, the private boys school he went to in rural New Jersey and in a project to restore an old house there. He went on to receive a BA in advertising design from Syracuse University, and after two years in the Army, received an MFA in graphic design from Indiana University.

COURTESY BRUCE CAMPBELL

Campbell became a graphic designer of renown, and although his home has long been in Vermont, he took weekly train trips to meet with design clients in New York City. He had first started working on wire sculpture in the early 1990s, and he carried his tools with him on the train. Soon they outweighed his other luggage, especially when his work became more complex around 2001, after introducing the concept of movement to his sculptures. The parts are made by hand without lathing or milling machines. Says Campbell, “I do not want the perfection of highly machined parts but instead prefer to have the hand of the maker evident.” Both objects and concepts animate Campbell’s work: with salvaged wood for a base, cotter pins, nuts, and coat hanger wire become butterflies and falling rain. The title of one work, Portable Universe, reflects his early studio mobility.

Campbell was named design director for the Library of America in 1981. He has designed books for the Metropolitan Museum of Art for thirty years, as well as for the Whitney Museum, the National Gallery of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Art Institute of Chicago, among many others. His work has won numerous awards. His sculpture is currently shown at David Walter Master Craft Gallery in Brattleboro, Vermont, the River Gallery in Essex, Connecticut, and the Cate Charles Gallery in Providence, Rhode Island.