JOSEF ALBERS MUSEUM QUADRAT BOTTROP, 1976 © 2016 JOSEF AND ANNI ALBERS FOUNDATION/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/TIM NIGHSWANDER PHOTO

JOSEF ALBERS MUSEUM QUADRAT BOTTROP, 1976 © 2016 JOSEF AND ANNI ALBERS FOUNDATION/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/TIM NIGHSWANDER PHOTO

Feature

Bright and Beautiful

IN THE 1930s, JOSEF AND ANNI ALBERS made the first of many trips to Mexico. There’s a picture of Josef Albers taken by Anni at Mitla in Oaxaca about 1937. He’s in profile, and behind him, filling the rest of the frame, are the frenetic, step-fret forms of the stone mosaics that drew archaeologists to the Zapotec site. The photo—these people and this place— conjures the radiating ziggurats of Josef ’s lithographs and paintings, and the meandering yet purposeful patterns of Anni’s screen prints and weavings, and suggests the depth of influence this region and its culture had on the artists.

With their first visit to Mexico, Josef and Anni Albers began collecting pre-Hispanic art and over the next three decades they honed their eyes and focused their interests. By 1966, when they first gave part of their collection to the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, the Alberses had assembled more than fourteen hundred “Small-Great Objects,” as Anni called them, including Mayan and Aztec figures, Andean pottery and textiles, and hundreds of Chupícuaro and Tlatilco clay figurines, as well as artifacts from other ancient cultures spanning the Americas.

Jennifer Reynolds-Kaye, curator of Small-Great Objects: Anni and Josef Albers in the Americas at the Yale University Art Gallery (February 3 to June 18), discusses the Alberses’ approach to building their remarkable collection and how the collection, in turn, shaped their own activities as artists, writers, and educators.

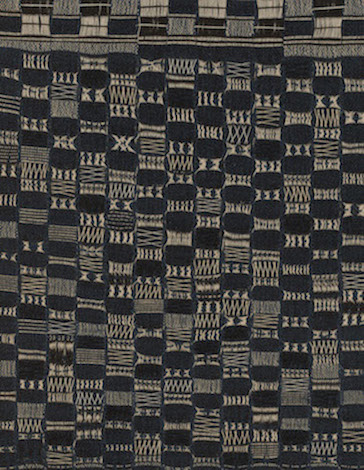

Anni Albers, Thickly Settled, 1957. Cotton and jute. Yale University Art Gallery, Director’s Purchase Fund. © 2017 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Standing female figurine, Mexico, Guanajuato, Chupícuaro, 400–100 B.C.

Jenny Florence: When did the Alberses first encounter pre-Hispanic art?

Jennifer Reynolds-Kaye: The earliest that we know is in 1908, when Josef visited the Museum Folkwang, which was in Hagen. So they were looking at pre-Hispanic art in Germany, even before they had left [for the United States in 1933]. In the 1900s, 1920s, some of the best collections of pre-Hispanic objects and Andean textiles were in Berlin and in other cities in Germany.

So long before they had set foot in the Americas. When did they first visit Mexico?

Their first trip to Mexico was from December 26, 1935, to January 21, 1936, and they visited Mexico City, Oaxaca, and Acapulco. That’s their first trip. I have more documentation from the second trip and onward, but that’s the first time they went there.

Was the second trip more significant?

It’s more that the heart of my archival work was the letters that the Alberses sent to Bobbie and Ted Dreier—Ted Dreier was one of the founders of Black Mountain College—and they sent letters back and forth in the ’30s, primarily, and those had not been fully mined until this exhibition. They were a great glimpse into what the Alberses were thinking, what they were collecting, who they were meeting with, where they were staying—a day-to-day record of both Josef ’s and Anni’s perspectives.

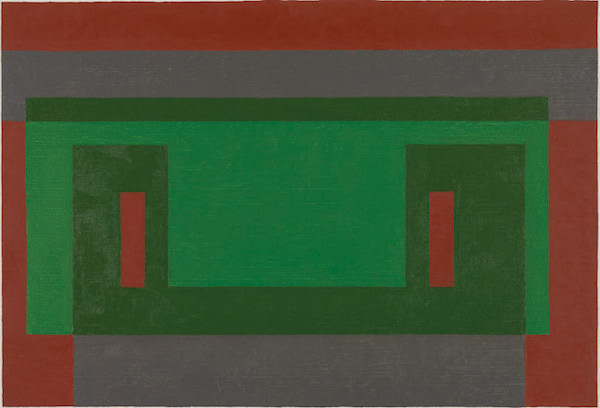

Leaf-green Wall, painting by Josef Albers 1958. YALE UNIVERSITY ART GALLERY, GIFT OF ANNI ALBERS AND JOSEF ALBERS FOUNDATION, INC., 1977 © 2016 THE JOSEF AND ANNI ALBERS FOUNDATION/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK

What was it about this kind of art that first attracted them?

It’s hard to say exactly. In their letters they were writing more about impressions of the sun and having time to work, and those friendly back-and-forths [with the Dreiers]. But I think what first drew them were a few things. One is the idea that these clay objects were fully clay. The Alberses held a “truth to materials” idea from the Bauhaus on and they were interested in the stoniness of stone, the clayness of clay. I think they also marveled at the way these objects had survived, and in such pristine condition in many cases. So this idea of timelessness and aesthetic truth being pulled through from far in the past.

Color and variations on a theme are two things that I think they were also drawn to. Those three hundred Chupícuaro figurines have the same basic head, body, and arms, but they are all slightly different, there’s variety. It’s very reminiscent of Josef ’s Homage to the Square series in that there’s a basic visual formula and he’s able to create different effects based on how the colors are working together.

And Anni was really blown away by the textiles. The fact that they had survived, the techniques, the patterns. It was something that she really connected with.

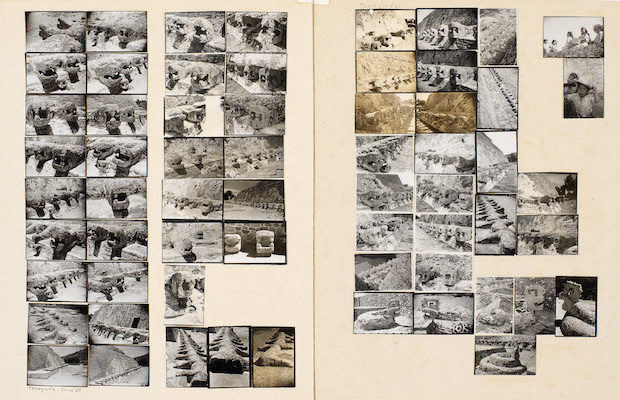

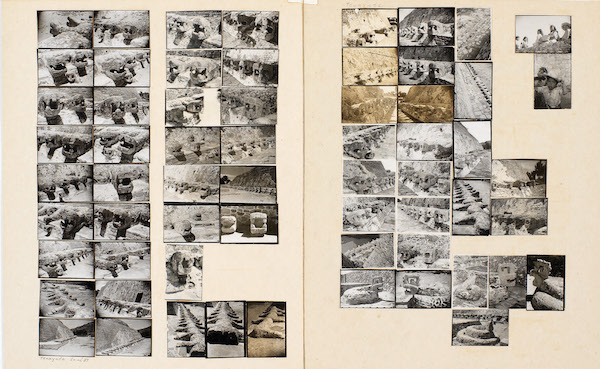

Monte Albán ’35/ Monte Albán, photo-collage by Josef Albers 1935–1939. JOSEF ALBERS MUSEUM QUADRAT BOTTROP, 1976 © 2016 JOSEF AND ANNI ALBERS FOUNDATION/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/TIM NIGHSWANDER PHOTO

How did they begin to collect the objects and where did they acquire them?

Anni writes in her book Pre-Columbian Mexican Miniatures about how they started by going to archaeological sites where kids would approach them and offer to sell them a little ceramic figurine they had found. So it began as an informal, very affordable collection, and they were starting in markets and archaeological sites. But over time it ramped up. Moving from North Carolina to New Haven helped in that there was proximity to the New York art market, and they were getting invitations from the André Emmerich Gallery and others. And we have a handful of receipts that indicate that they were spending a good amount of money. And when they weren’t buying things outright, they were oftentimes exchanging Josef’s artwork for pre-Hispanic pieces.

In his “Truthfulness in Art” lecture Josef said, “Let us be no all-eater, no all-reader, no all-believer, let us be selective instead of being curious.” How did this notion of selectivity inform the Alberses’ collecting?

I think you can tell from the composition of the collection that they weren’t trying to create a comprehensive history of pre-Hispanic art. They were being selective in their interest in small hand-held figurines, mostly Tlatilco and Chupícuaro. It’s a very idiosyncratic process where they honed in and by training their eye they developed this connoisseurship. They were able to determine what was authentic and what was inauthentic.

They really juxtaposed themselves against someone like Diego Rivera, who was embracing any object he could get his hands on, and they’d said no, we’re being selective, we’re being thoughtful about this.

So it began informally and as it grew more formal, they became more discerning collectors and had a better appreciation of what they were looking for.

Yes, and part of that training the eye was through Josef’s photography, this intense looking at an object from all angles and capturing that in his photographs and later showing that as photo-collages.

I read that they didn’t display the objects in their home, which struck me because so many other artist- or designer-collectors of the mid-twentieth century displayed their collections. But the Alberses stored their pieces. How do you think they saw their collection?

That’s a good question for Nicholas Fox Weber [executive director of the Albers Foundation]. My primary work has been thinking about what they collected, and connecting it with what they photographed or wrote about. I haven’t found any documentation or letters that describe where they kept them or how they stored them. We have these photographs that were taken to encourage other museums to acquire the pieces, but I think they were private about it and I’m not sure why. The photo-collages [of the pre-Hispanic objects and sites] were never shown, and I don’t think the photographs were necessarily on display either. Is it a radical act to bring all this out into the open?

Untitled photogragh by Josef Albers of a Pre-Columbian figure in the Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City. JOSEF AND ANNI ALBERS FOUNDATION © 2017 JOSEF AND ANNI ALBERS FOUNDATION/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK

Tell me about the photo-collages. Are these very different from Josef Albers’s Bauhaus photo-collages?

There are two different focuses. I’m thinking about these photo-collages as showing a collector’s impulse. Wanting to capture a three-dimensional object in a two-dimensional medium. That’s my reading of the photo-collages of the pre-Columbian objects at the museum. He also made photo-collages of archaeological sites—there will be a few of those in the show. He brings together images from different time periods, too, so there could be one contact print from 1936, another from 1939. Time and place are put together in an interesting way in some of those pieces.

And he never exhibited the photo-collages that he made of the pre-Hispanic art and sites?

Not that we’re aware of, because they were found in [the Alberses’] house in boxes. I think it was surprising to see the quantity of photo-collages and also the variety of subject matter.

You write in the exhibition catalogue that Josef Albers disliked museum labels that put objects in historical context. Is this something you were thinking about when you approached your own exhibition?

Oh, yes. That’s something I’m managing right now. I’m trying to reduce the amount of text and labels, but inevitably we have to have labels. It’s the nature of the museum. But I proposed that and thought, what are strategies to have very minimal signage? I’m very sensitive to that desire that Josef had, but I’m coming up against the requirements of the museum.

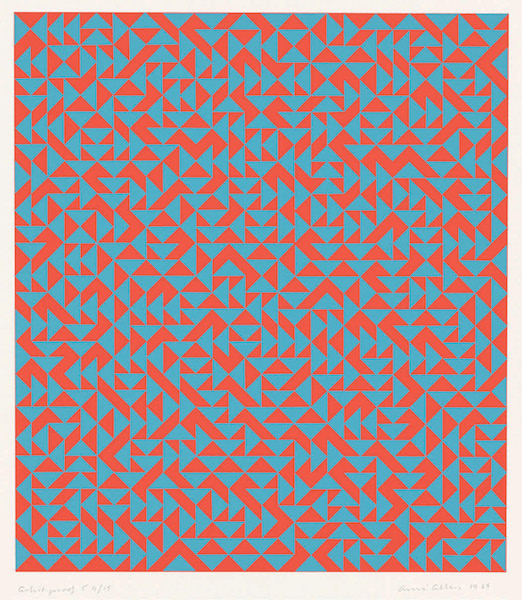

Triadic C, screenprint by Anni Albers, 1969. YALE UNIVERSITY ART GALLERY, HENRY S. F. COOPER, JR., B.A. 1956, CONTEMPORARY PRINT FUND © 2016 JOSEF AND ANNI ALBERS FOUNDATION/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK

What kinds of material are in the exhibition?

We’re focusing on objects, primarily, so we’re bringing out a selection of the fourteen hundred pieces that the Alberses collected that are at the Peabody and at the Albers Foundation and reuniting those with some of the sketches and with Josef’s photographs and photo-collages, some of the Variant and Adobe works, and work from various other series, including Homage to the Square. We have Anni’s textiles and also selections [from the Harriet Engelhardt Memorial Collection] that she made for Black Mountain College, along with some necklaces that she designed based on [necklaces found at] Tomb 7 at Monte Albán. And we’re very lucky to have on loan from the Smithsonian [American Art Museum], Anni’s Ancient Writing, which will be a highlight. It hasn’t traveled in a long time. It’s a sister piece to Monte Albán, which was in the [2015] Black Mountain College show [Leap Before You Look].

And how was the Alberses’ work informed by the collection? How did Josef digest the material into his own artistic practice and pedagogy?

The main teaching and theorizing that I’ve been able to document is from that “Truthfulness in Art” lecture that he gave at Harvard. That, to me, is the key to unlocking his perspective on the art that he collected and that he photographed and the principles he extracted for his own work. There is some visual resonance between what they saw and collected in works like Tenayuca (the original painting Tenayuca is at SFMoMA). And of course there are the Variant and Adobe works. There’s a photo-collage in which Josef puts two adobe windows next to each other, and visually and formally that was very similar to the format that he created for the Variant and Adobe work from which we’ll have examples in the show. And that’s often thought of as the predecessor to the Homage to the Square series.

And what of his ideas of “fallibility of perception,” which you also write about in the catalogue.

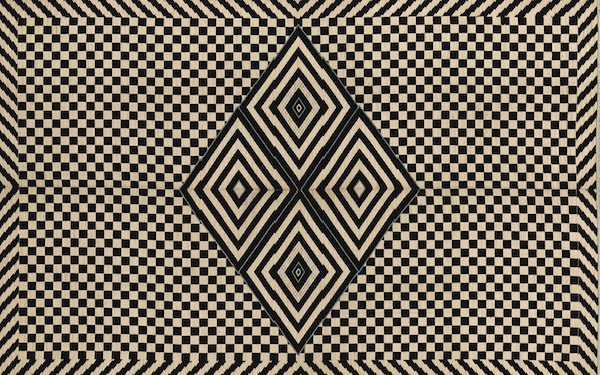

Yes, to me that is central to [his book] Interaction of Color and also something that you see particularly in Andean textiles, the masterful way [the Andean artisans] were able to create a confusion between foreground and background, or some of the textiles with series of diagonal lines that could be simultaneously the wing of a bird or ocean waves. There are these moments where the pattern is unresolved and it’s continually resolving in your eye. I don’t think Josef writes explicitly about Andean textiles, but I think that you can make those connections intuitively.

Serape, Mexico, Querétaro, late 19th to mid-20th century. YALE UNIVERSITY ART GALLERY, HARRIET ENGELHARDT MEMORIAL COLLECTION, GIFT OF MRS. PAUL MOORE

What about Anni? How do the collections emerge in her work?

With Anni one of the things I’m noticing between the work she collected and the work she made was an interest in triangles that you see picked up from the Andean textiles, a ceramic vessel that she selected, and pieces like Triadic C, where triangles are being used in really interesting ways. I wouldn’t say that this was the source but it was a point of synergy in her work. And with the Andean textiles, the different types of open weave, the way they were able to do the double weave. I haven’t been able to delve as fully into the specific techniques and where I see them in her work and in the things she collected, but I think she was really interested in collecting a broader range—counter to [the way they collected] the three-dimensional objects, which they were very specific about. For the teaching [Engelhardt] collection she created for Black Mountain College, she was trying to express the different possibilities of that intersection between warp and weft.

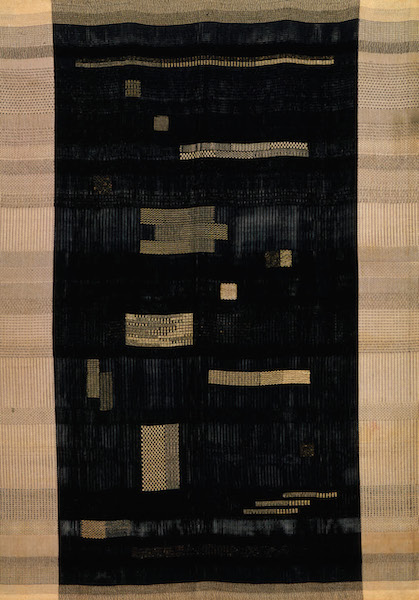

And what about Ancient Writing?

She made Ancient Writing and Monte Albán in 1936, so right on the heels of their first trip. Monte Albán is a beautiful landscape, very reminiscent of the Zapotec site Monte Albán. For me, Ancient Writing is slightly different in that it’s more about textiles as a portable and durable form of communication, which is something that she was interested in, and then textiles as part of an architectural heritage. That’s a core part of the show. She writes about this in her book On Weaving.

Ancient Writing, weaving by Anni Albers, 1936. SMITHSONIAN AMERICAN ART MUSEUM, GIFT OF JOHN YOUNG © 2016 JOSEF AND ANNI ALBERS FOUNDATION/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK

It seems like she also learned a lot during those trips to Mexico, seeing women weave traditional textiles on backstrap looms . . .

Yes, and I’ve been so confounded by that! How did they do that with a bunch of sticks? It’s really amazing technology.

And one of the objects in the collection is a back-strap loom with an unfinished weaving on it.

Yes, there are certain pieces in her private collection that look like they are unfinished. I think this idea of them being unfinished was really attractive to her. There are some ancient Andean textiles that look like they were just removed from the loom. They still have all this unfinished warp, and there’s this sense of the process. There’s evidence that Anni might have been actively undoing some of the textiles to learn how they were made.

What do you see as the legacy of the collection?

For me, the Alberses were really educated by this art, and this material could be used by the Peabody Museum or the Yale Art Gallery in teaching about textiles or about pre-Hispanic objects. I think that was the legacy that they intended for it. Also, part of their legacy could be in the photo-collages. The Alberses were [in Mexico] in the thirties, which was the height of archaeology there, and I think that that could be part of the scholarly legacy as well, encouraging people to look at these photos.

One question that I’m still working through is how the Alberses’ investment or engagement in pre-Hispanic art either fit into or challenged a reevaluation of “primitive art” in modernism. That’s a question that I haven’t figured out yet and I’m hoping that the dialogue created by the show will help work through this a little bit. Also, how does this work fit into the history that’s being told right now about this moment and this idea of a global modernism? This material still feels very fresh to me and there’s still so much to work on.