All images courtesy of Chicago Cultural Center. Except as noted, all photography by James Prinz.

All images courtesy of Chicago Cultural Center. Except as noted, all photography by James Prinz.

Exhibition

The Influence of African American Designers in Chicago

Design, like a number of industries, hasn’t always been an inclusive one, often overlooking the significant achievements of many players—particularly women and African Americans—who have shaped the field. A new exhibition in Chicago is righting this wrong by taking a closer look at the contributions of African Americans to design—from graphics to products to transportation. “Our main goal was to survey all of the archives that we knew about and utilize them to serve this very broad study of the experience and work of African-American designers in Chicago over much of the twentieth century,” Daniel Schulman, director of visual art for the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs and curator of African American Designers in Chicago: Art, Commerce, and the Politics of Race, explained in a recent interview. The exhibition addresses the “failure of design historians to look at the history of the participation of African Americans in various design fields,” he added.

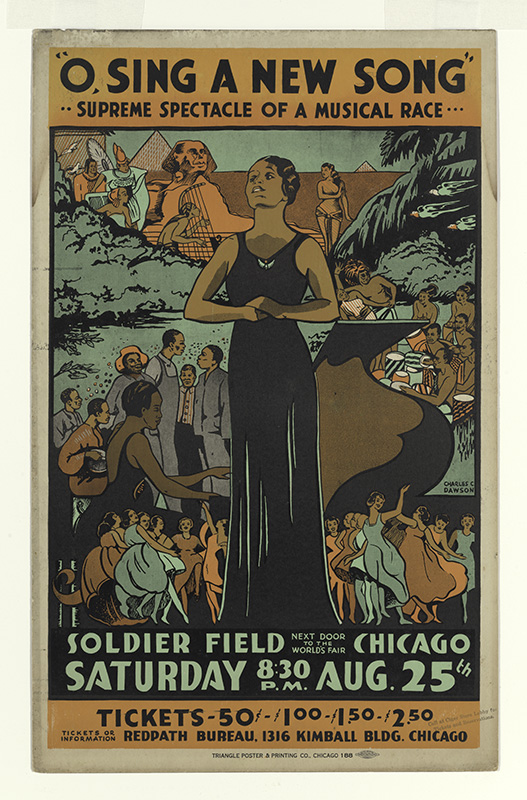

“O Sing a New Song,” by Charles C. Dawson, 1934. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Reba and Dave Williams; image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Long in gestation, the project came out of meetings between Victor Margolin, professor emeritus of design history at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and Charles Harrison, who worked as the director of product design at Sears and became the first African-American executive at the company in 1961. Harrison introduced Margolin to a “constellation of African American designers in Chicago,” which led to the discovery of lost and forgotten archives. These archives, along with oral histories conducted by Margolin, form the foundation of the show’s scholarship. Chicago was the perfect ground zero for the study, due to its importance in the early twentieth century as a manufacturing center and its established African-American consumer market. “There was no research in this field whatsoever outside of what Victor had done,” remarked Schulman, underscoring the importance of the exhibition. “Issues of representation both in terms of imagery and in terms of who’s doing the designing and who these designers are working for is being unveiled here in a coherent way for the first time that we know of.”

Patty-Jo doll by Jackie Ormes, 1947. Courtesy of Nancy Goldstein.

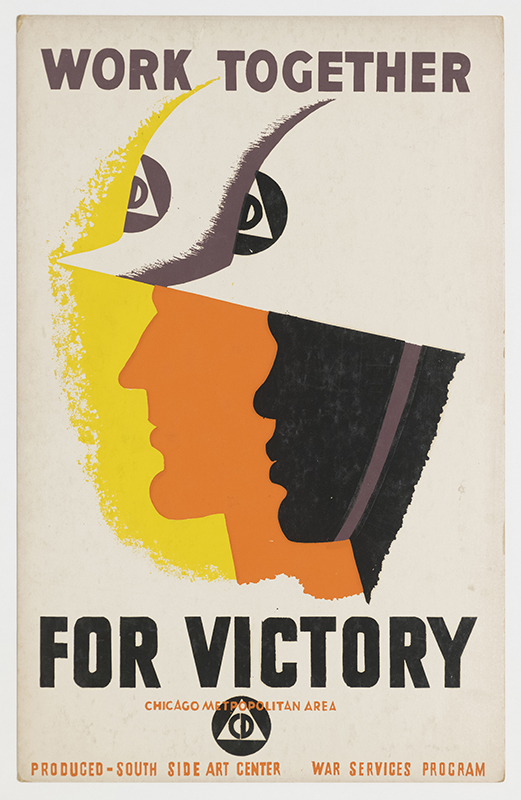

Though there are some finished products, the show consists mostly of ephemera: letters, cartoons, sketches, working mechanicals—displayed in cases and vitrines created by exhibition designer David Hartt. Charles Harrison is heavily represented, along with cartoonist Jay Jackson, designers Charles Dawson and Emmett McBain, among many others. One of the most significant pieces in the exhibition is a rare doll designed by Jackie Ormes. Even though it was aimed at a broad market of African-American girls, “the production standards of Ormes were so high that it priced it out of the range of most consumers,” Schulman explains. “Ormes was a talented and tireless champion for women as entrepreneurs and as people who could change perceptions and influence lives,” he added. The influence of the Chicago Bauhaus, too, is prevalent, especially in the work of Eugene Winslow and Thomas Miller. Winslow even wrote about how deeply influenced he was by the universal principles of design promoted by the Bauhaus, giving him a broader perspective on his work and opening him up to new ways of approaching society and industry. Even though many of these designers worked in atmospheres rife with racism, Bauhausian concepts—free of nationalist interests—were a liberating revelation for African-American design students. Though not encyclopedic, the exhibition’s variety offers a thorough look at the role Chicago-based African-American designers played in creating an image for advertisers, manufacturers, and consumers, who “were both black and white,” Schulman says.

Together for Victory by an unknown designer, c. 1942. William McBride Papers, Vivian Harsh Collection, Chicago Public Library.

Looking forward, Schulman and his colleagues plan to release a book that will draw from the exhibition’s research. “It’s a deep and complex area of study and I think we just scratched the surface,” Schulman says. “We wanted to offer this as a starting point for people to have the archival material to prompt new questions.” With this trove of material now available for researchers, along with Chicago’s growing design scene (including the fledgling Chicago Design Museum and the city’s architecture triennial), African American Designers in Chicago situates itself as an important addition to a larger, national conversation between designers, historians, and manufacturers about the contributions of minorities in all fields of design.

African American Designers in Chicago: Art, Commerce, and the Politics of Race is on view at the Chicago Cultural Center through March 3, 2019.