© PIERRE PAULIN/GEORGE MEGUERDITCHIAN PHOTO, © CENTRE POMPIDOU, MUSÉE NATIONAL D’ART MODERN

© PIERRE PAULIN/GEORGE MEGUERDITCHIAN PHOTO, © CENTRE POMPIDOU, MUSÉE NATIONAL D’ART MODERN

Exhibition

A PIERRE PAULIN RETROSPECTIVE IN PARIS

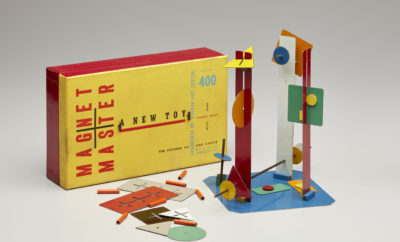

IN THE 1960S AND 1970S PIERRE PAULIN enjoyed a global reputation as the best known of a new wave of postwar French designers and interior architects. Among his many furniture designs, his Mushroom, Tongue, and Ribbon chairs achieved cult status. In 1968 the Museum of Modern Art in New York acquired his F300 lounge chair and F577 Tongue chair for its permanent collection, and in 1969 he received the Design Award of the American Institute of Interior Designers, Chicago. The full fifty-year arc of his career, spanning the second half of the twentieth century, is the subject of a major retrospective on view at the Centre Pompidou in Paris until August 22.

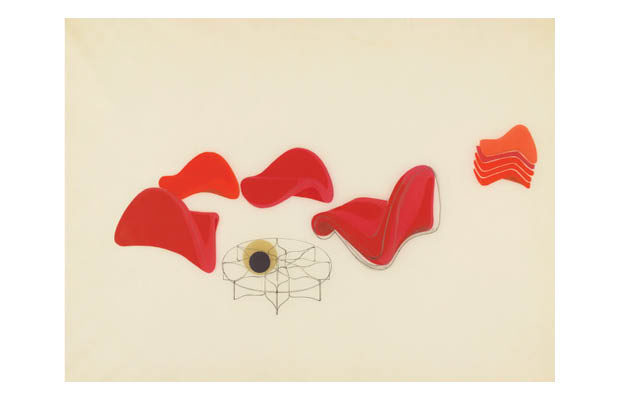

Eclectic and experimental, Paulin’s style reflects multiple influences—the functionality and human scale of Le Corbusier; the pragmatism of Charles Eames; the plain, almost severe, purity of Alvar Aalto; and Scandinavian and Japanese architecture and design. A common thread is the coupling of opposites—austerity and sensuality, plain materials and playful colors, hard surfaces with softened edges and curvaceous forms. He pushed the boundaries with new materials, pioneering the use of slip-on stretch jersey fabrics, polyurethane foams, and molded plastic as upholstery over light tubular steel frames.

Born in 1927, he trained as a ceramist at the famous Vallauris pottery near Cannes and as a stonecutter before entering the Camondo design school in Paris and then linking up with Marcel Gascoin and the avant-garde Union of Modern Artists grouped around Robert Mallet-Stevens. He first came to public view in 1953 with a metamorphosing daybed and a suite of affordable living room furniture that won acclaim at the Salon des Arts Ménagers, the Paris equivalent of the Ideal Home show. Taken on by the Galeries Lafayette department store as an in-house designer, he later worked with a series of design studios and manufacturers and also won prestigious private and public commissions, including the refurbishment of the private residence in the Élysée Palace for President Georges Pompidou in 1971 and the Élysée offices of President François Mitterrand in 1984. When Paulin died in 2009, President Nicolas Sarkozy issued a communiqué in his honor, calling him the “man who made design an art.”

The Pompidou show’s curator, Cloé Pitiot, has brought together more than a hundred pieces of furniture, drawings, maquettes, and archival material, much of it drawn from an exceptional donation of Paulin’s work and documents made by his heirs to the museum in 2015. Iconic pieces are mixed with others that have rarely, if ever, been shown to the public, including some early examples from the 1950s, prototypes for designs such as the Carpet chair, and projects that never made it into production. “Paulin researched the use of stretch fabrics that could be slipped on like a swimming costume. It was a revolutionary idea,” Pitiot says. “In the ‘60s, with models like the Tongue and Carpet chairs, he got rid of chair legs, he pioneered low-level living, the idea of sitting on the floor, living on the floor. It was a new way of life. In the ‘70s he worked on all these elements to develop a total look. Everything was thought out, from door knobs to furniture to lighting. It was a really novel approach.”

Organized chronologically, the show illustrates Paulin’s successive collaborations with innovative European furniture and lighting manufacturers such as Thonet, Disderot, and Artifort. Also on display are more classically inspired pieces created in the 1980s for the Mobilier National—the French state agency charged with furnishing government offices and official residences; and a re-creation of the living room at La Calmette, the retirement villa Paulin built for himself in the Cévennes mountains of south-central France in the 1990s.

In a user-friendly nod to his focus on bodily comfort, a selection of recent editions of his furniture is installed in a rest area/video room halfway through the show, where visitors can pause and enjoy the practical application of the designer’s maxim: “Design is a collective practice at the service of the public.” centrepompidou.com