Paul Clemence Photo

Paul Clemence Photo

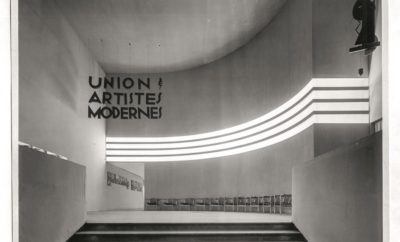

Architecture

A Conversation with the Pompidou’s Christine Macel

ART AND ARCHITECTURE have always been part of Christine Macel’s life. The director of this year’s Venice Biennale, she grew up with an architect father, started her career in New York City as an intern at the Guggenheim Museum SoHo, and is currently chief curator at the Musée National d’Art Moderne at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, where she founded (and still heads) the department of contemporary art. As she was readying herself to tackle the challenge of putting together the Biennale at the historic Arsenale and Central Pavilion in Venice, MODERN had a chance to catch up and talk about her recollections of the opening of the Pompidou, and about museum architecture and the relationship between art and unexpected spaces.

Jacopo Salvi Photo/Venice Biennale

PC: As the Centre Pompidou, the iconic museum building by Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano, is celebrating its fortieth anniversary this year, could you speak a bit about your memories of the project going up and of your first visit there?

CM: The opening of the Pompidou in 1977 was a massive event. I went with my parents. I was only eight, but my father is an architect, so I was used to looking at architecture a lot and even going on the construction sites of his buildings. But, strangely, it’s not the building itself I remember as much as the works inside, which gave me a definite shock. I have a very strong memory of Chopin’s Waterloo [1962] by Arman, a piano cut into pieces on a wood panel. I was totally fascinated, and always associate contemporary art with this gesture of freedom and great inventiveness. I also remember the work of Ben, a French Fluxus artist who had transformed his own shop and gallery in Nice into an installation called La Maison (The House), not to mention—for reasons you might imagine, given my age at the time—the hyperrealistic nude couple by John De Andrea.

One of the artists to be included at this year’s Venice Biennale, Edith Dekyndt, presented her installation titled One Thousand and One Nights at the Brussels-based WIELS art center in 2016. It featured a carpet of dust collected over the course of a year on which a spotlight was shined, shifting positions throughout the day. Sven Laurent Photo/Courtesy the artist and Galerie Greta Meert, Carl Freedman Gallery, Galerie Karin Guenther, Konrad Fischer Galerie

PC: How do you think the project has aged?

CM: It’s a building that needs a lot of care, a budget every year to maintain itself, so it is not an easy one to deal with. Soon after it opened it was already too small and the curators had to move into buildings nearby. But despite its natural aging and several changes through the years, to me it remains a very fresh building. I never get tired of it. It keeps a vivid energy of the ‘70s.

PC: How do you think the Rogers and Piano design has affected the typology of museums and how we think about museum spaces?

CM: Their idea of a museum opened to the outside— with the Pompidou’s initial Forum opened to the Piazza on all sides—was a key idea. It created a totally different relationship between the public and culture. Previously, museums had been intimidating, with entrances designed to create a feeling of grandeur. In my mind, the success of the Pompidou is based on its positioning toward the public, both on an architectural and a curatorial level.

PC: Architecture critics have very strong opinions on museum architecture, but often without actual feedback from two of the most important users: visitors and curators. From your long experience as a curator, what are some of your thoughts about museum architecture?

CM: I like museums that have their identities without trying to compete with the art itself—and that offer the works the space they need—and also architecture that is thought about from the human point of view. Good museum architecture should be strong but generous. That is why I love Renzo Piano’s museums so much, particularly, for instance, the Fondation Beyeler, which I believe perfectly addresses all of these criteria.

PC: How does architecture affect and inspire your curatorial decisions and approach to exhibitions?

CM: As you may guess, it is a crucial point. I always go to see a space before thinking about an exhibition, because the space gives the framework—and it also has a strong impact on the narrative you want to develop or the choice of artists you imagine dealing with. For example, when I curated the exhibition What We Call Love: From Surrealism to Now at IMMA [Irish Museum of Modern Art] in Dublin, I had to adapt a space with small rooms and a long corridor, which appeared at first to be difficult to work with, but in the end, gave the show a very interesting rhythm.

Christine Macel curated the 2011–2012 exhibition Danser Sa Vie at the Centre Pompidou. © Centre Pompidou

PC: You have curated two Biennale national pavilions before at the Giardini (for Belgium in 2007, and France in 2013). But now, of course, as director of the entire event, it is a much larger undertaking. What has been your approach to conceptualizing the presentation at Arsenale and the Central Pavilion?

CM: The Central Pavilion in the Giardini cannot be touched so you have to use it as it is. The real challenge is the Arsenale, which has to be entirely rethought and reconstructed for each show. I have asked Jasmin Oezcebi, who is an architect I respect a lot for her eye and her skill in building minimal and subtle museographies, to work with me. She recently designed the Picasso and Giacometti show at the Musée Picasso in Paris and it was marvelous. For the Biennale I gave her a map and general ideas, and she has done, I think, a wonderful job, balancing the needs of each work, creating a recognizable architecture but with discreet gestures, and keeping the whole show open and fluid. And that is not easy.

PC: You have worked in many distinguished cultural venues all over the world. What is one that inspired you in a special way?

CM: Historical buildings with a story always inspire me. It is much more challenging than the white cube. So I would say that my stronger memories are linked to unexpected spaces. Of course, I also immensely enjoyed designing the Danser Sa Vie exhibition of 2011 to 2012 in the huge two-thousand-square-meter space on the sixth floor of the Pompidou— and collaborating with architect Maciej Fiszer on it. But the real challenges come from unexpected spaces, such as when I curated the Festival du Printemps de Cahors in 1999 and 2000, in Cahors, a small city on the Lot River in France, where I had to deal with inside and outside spaces for about fifty artists and design a path through the city. Or when I curated Nel Mezzo del Mezzo in Palermo involving more than sixty artists in five different venues—all historical buildings, including an amazing chapel where kings used to be coronated. That space itself gave the inspiration to include two artists working with a spiritual dimension, Rachid Koraichi and Younes Rahmoun: the result was an indescribable feeling of harmony that would never have been reached in a white cube.

The Centre Pompidou (right), which opened in 1977, made culture more readily available to the public through the design of an inviting piazza, the Place Georges Pompidou. Paul Clemence Photo