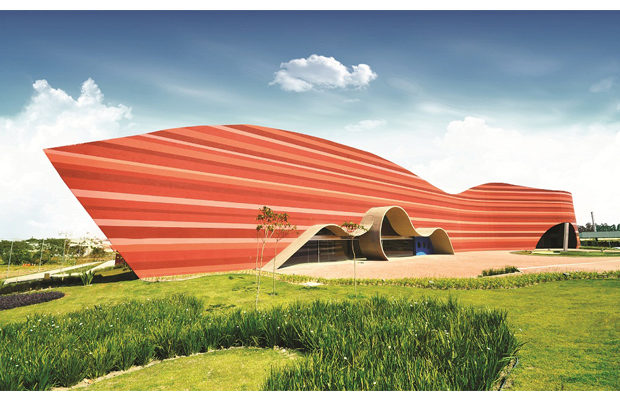

The Jacareí Cultural Center, 2015, in the city of Jacareí, Brazil, is one of Ohtake’s most recent projects.

The Jacareí Cultural Center, 2015, in the city of Jacareí, Brazil, is one of Ohtake’s most recent projects.

Feature

Ruy Ohtake: Brazil’s Living Architectural Legend

THE BRAZILIAN ARCHITECT RUY OHTAKE has the courage of his convictions. When one speaks to him, as I have been lucky enough to do several times, there are no sound bites, no statements, no public relations talk. It’s just an architect speaking genuinely, with the self-assurance that comes from hard work and a job well done. At 77 Ohtake retains a refreshing natural enthusiasm, as excited today to talk about his designs as he might have been as a recent graduate speaking about his first project.

Ohtake is one of Brazil’s most prolific architects and has designed buildings across the country over five decades, with more than 420 built projects (close to three hundred of them in the city of São Paulo alone)—an architectural feat to be celebrated anywhere, but especially in a country that has been plagued with political and financial turmoil. He has designed cultural institutions, residential and office towers, hotels, banks, transportation hubs, an aquarium, sports arenas, houses, and even an elevated mass-transit expressway (with guard rails painted canary yellow). In São Paulo, a megalopolis of intense architectural cacophony, he has without a doubt left his mark.

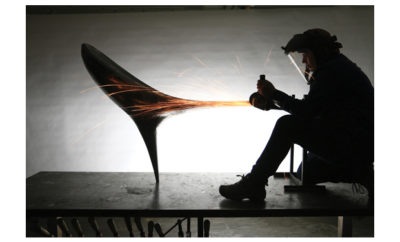

Ruy Ohtake at the Tomie Ohtake Institute.

His Hotel Unique is seen by many as the quintessential symbol of the upward wave Brazil has been riding since the beginning of the century. Its design encapsulates many of Ohtake’s conceptual ideas, in particular the use of sculptural shapes and bold color to create surprise. “To give room for the unexpected to happen,” Ohtake comments, “that was one of the lessons from Oscar,” referring to the legendary Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer, whom he considers a mentor (alongside his former teacher, architect João Batista Vilanova Artigas).

The Unique is shaped as a half-circle. Ohtake tells of the dispute that arose over the guestrooms that would have a wall delineated by the arcs of the semicircle: “The marketing experts said that would be a problem, that guests would not want that. But I argued with them, and an agreement was reached that there would be a provision for built-in armoires in front of the sloping walls—but that first we would test what the reaction would be without them. The original design was a success, and today those rooms are considered the VIP rooms, with higher prices and in high demand, usually with a waiting list.”

The Sacomã Bus Terminal, 2007, in São Paulo.

In discussing his use of concrete in the building—it pushes the structure to its limits while creating a dynamic play of volume and void—Ohtake defines his attitude toward design: “I am interested in creating shapes that can surprise people, that are daring, that use cutting-edge engineering technology to innovate space.” A true believer that form precedes function, he states: “We see this happening all the time: landmark historic buildings being re-adapted for new uses. A well-designed building will have significance even after the original function it was created for is outdated.”

After voluptuous shapes, color is the element most associated with Ohtake’s work. And not just any color—bright, strong, vivid colors. Even though Brazil is primarily tropical and sub-tropical with exuberant flora and fauna and a rich and diverse culture, its architectural establishment has leaned toward natural, neutral, sedate earth tones more aligned with European tastes. So when Ohtake started splashing his projects with deep purples, carmine reds, bright yellows, and even pinks, some reaction was unavoidable. But the architect was not intimidated: “If you want to create something new, original, you have to be aware that it could be controversial. But once the projects are ready, it stops being an issue,” he says. “Color is part of our lives. Color is universal—everyone responds to color!”

The extreme sculptural forms and bold colors of São Paolo’s iconic Hotel Unique epitomize Ohtake’s work. On the rooftop patio, a swimming pool is tiled a deep red. In some guest suites the floors sweep upward to meet the ceiling.

His fondness for color may have started early, as he is the son of acclaimed Brazilian artist Tomie Ohtake (who died earlier this year at 101), herself an exquisite colorist. But his aesthetic incorporates an interesting mix of influences, including the excesses of the eighteenth-century Brazilian baroque, the graphic iconography of Joan Miró, and the subtlety of Mark Rothko. He speaks with great admiration of Aleijadinho, one of Brazil’s foremost baroque sculptors and architects, who created both carvings and churches with grand gestural lines and sparkling interiors covered in gold leaf. Architect and cultural producer Denise de Alcantara-Hochbaum, who has spent years in São Paulo, observes: “Ohtake’s very personal architectural vocabulary really stands out in the gray cityscape of São Paulo.”

Beauty, too, is of great importance to Ohtake— and another important legacy from Niemeyer: “He gave us freedom to value beauty, to be poetic and to have pride in creating beauty, something that was not popular with the modernist dogmas back then,” Ohtake says. (And one could argue that it remains the case today, when concept seems to override the basic desire for beauty.) But even with such strong convictions regarding architecture’s power of seduction, Ohtake believes that the architect’s most important commitment is to a building’s presence in the city and to the end user.

The Tomie Ohtake Institute, named after Ohtake’s mother, one of Brazil’s most important artists, who died in February 2015. Tomie Ohtake was known for her abstract paintings and the boldly colored compositions of her sculptures.

Thus one of the most meaningful projects of his career stands far from the glare of the glass curtain walls of São Paulo’s business center. Instead, it is right at the heart of Heliópolis, the city’s largest favela (and Brazil’s second largest, after Rio de Janeiro’s Favela da Rocinha), with more than 120,000 inhabitants. Since 2003 Ohtake has developed a close relationship with the community through design and architecture. He was asked to come and help and agreed to do so, but only if all involved participated. At first it was to be a simple beautifying initiative—painting the humble dwellings assorted colors—but it quickly became much more. Ohtake persuaded the paint manufacturer, Suvinil, to go beyond just donating the paint and labor for the job, and instead to train the local residents to do the work properly, giving them a new set of skills.

For Ohtake, it was about empowering them. In his words: “I learned that the architect must have the professional side, where he gets the job and then delivers it, but with some clients the citizen side is just as important—there has to be a dialogue with the community.” That is easy to say, of course, and can sound slightly patronizing, but walk a couple blocks in Heliópolis and it is clear that Ohtake literally walks the talk, with appreciative residents stopping him every few meters to say hello or ask him in for a cafezinho or a sip of cachaça.

The “Redondinhos,” government-funded residential buildings in Brazil’s second largest favela, São Paulo’s Heliópolis, were designed by Ohtake after he had worked with the community for several years.

Twelve years, three municipal administrations, and many projects later, the latest installment of the collaboration, the “Redondinhos” (or “round ones”), government-financed residential condominium towers for the lowest income (minimum wage) population of Heliópolis, is moving ahead, with two new towers being completed this summer and phase three to be delivered by year’s end. In many aspects, from the density to the unit square footage to the location of the playground, the favela’s usually disenfranchised population has had a say, assuring that the design fits their needs rather than being imposed from above. Ohtake’s “work is very diversified but one constant element is that he is always committed to how the space will be used,” Hochbaum says. “He designs with the same vigor a project dealing with urban occupation in the slums as he does a sophisticated cultural venue like the Tomie Ohtake Institute.”

When architect E. Perry Winston, who specializes in affordable housing and teaches an international graduate planning workshop in Pratt Institute’s Programs for Sustainable Planning and Development (PSPD), had a chance to visit São Paulo with a group of students in 2013, they met with Ohtake. “He showed us not only his educational and low-income housing projects in Heliópolis but also his outstanding architectural solution to Hotel Unique, which sits in a low-rise residential neighborhood,” Winston says. “The visit broadened the scope of our workshop and demonstrated a sensitive, community-oriented approach to new architecture in low-income neighborhoods.”

Architecture can be polarizing—particularly when one stands out the way Ohtake does—and there are some who dismiss his work. But Ohtake remains open to the dialogue. “I welcome the critics,n as long as they come without prejudices,” he says. “The only problem is when criticism comes from preconceived notions. Because in the end architecture happens when it’s built; one has to experience it to know it, before any judgments.” At a time when Latin American architecture isthe subject of much research and discussion, from MoMA’s current exhibition Latin America in Construction: Architecture 1955–1980 (to July 19) to the many Lina Bo Bardi exhibits around the globe, it is the perfect moment to explore and experience the work of this architect who has so successfully trod an independent path—and is in constant creative evolution.

Paul Clemence is a photographer, writer, and blogger who specializes in architecture.