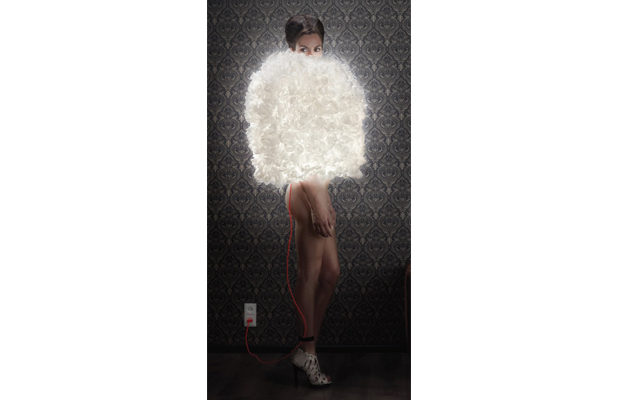

Wanders’s hybrid lighting fixture-fashion accessory Phoebe 3 floor lamp (made in an edition of three) is part of the Portraits exhibition at Friedman Benda in New York this spring.

Wanders’s hybrid lighting fixture-fashion accessory Phoebe 3 floor lamp (made in an edition of three) is part of the Portraits exhibition at Friedman Benda in New York this spring.

Design

The Wonders of Wanders

THE INIMITABLE DUTCH DESIGNER MARCEL WANDERS TALKS ABOUT HIS WORK AND WHAT HE CALLS ROMANTIC HUMANISM

MARCEL WANDERS has been prodigiously busy of late. The Dutch designer debuted a new lounge chair for Louis Vuitton in December. His Grandfather clock created for Christofle was introduced in January, as was a porcelain dinnerware collection (Blue Ming) for Vista Alegre that is a riff on the traditional Delft blue. His Monster Garden carpet, which he made in collaboration with the French textile firm Pierre Frey, is currently on view at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris; his work was also represented in an exhibition at the Design Museum Gent in Belgium. Wanders is at work on a prefabricated house—it is called Eden—for Revolution Prefabricated Properties, and recently completed the Kameha Grand Zurich Hotel.

In the last year his firm Moooi opened a New York showroom and, at Milan’s Salone del Mobile, launched Moooi Carpets. And most notably, Wanders is currently the subject of an exhibition at the New York design gallery Friedman Benda until April 9. MODERN caught up with Wanders as he inaugurated his rug collection at the Glottman showroom in Miami for a conversation that ranged from his carpet collection and the Friedman Benda exhibition to his philosophy about design.

His work always displays a particularly high level of design and detail and a love for unexpected, whimsical touches, whether at the scale of a teacup or an entire building. Often, especially in his hotels and other interior design projects, there is a feeling not unlike Alice’s in Wonderland—where what you thought would be small is big and what you thought should be big is small. Wanders also often invokes historical material culture, be it art or craft, reinterpreting it in ways that are both innovative and human.

Zliq sofa by Wanders for Moooi, 2012, in Jacquard old blue upholstery.

Beth Dunlop/MODERN Magazine: First, I thought we should talk your newest enterprise, Moooi Carpets. Can you tell me a little about those?

Marcel Wanders: So, we launched the Moooi Carpets last April in Milano. Basically we have found the technology where we can do high definition printing in any colors you want on carpets, which is kind of a unique feature. There is some existing printing of carpets, but mostly only in a few colors, like eight colors maximum. We do photographic printing, and this allows us to have a wide variety of designs for carpets and very different designs. And as you can see, the texture, the color, the quality are all super.

And there’s really nothing like it on the market. We can also do it for wall-to-wall, broadloom, which is kind of unique. We have a whole range of designers who’ve made designs for these carpets—or for broadloom—and by broadloom I mean there could be a corridor fifty meters long that starts with roses and ends with lilies.

MM: So you can turn your house into a garden if you want to.

MW: I feel so excited about it because it’s not a design for carpet. We created a new canvas for design. It is a new canvas.

MM: What was the inspiration for one of your favorite carpets, the Eden Queen.

MW: Now I love my country. We’ve had some amazing still life painters through the years, and I’m making a book about those painters now. This particular rug is a combination of flowers from different paintings. But it’s not a painting where we just put together a lot of flowers from different painters, just to mix them. We made our own bouquet.

The Zio buffet by Wanders, 2013, was featured in Moooi’s presentation at via Savona 56 during Milan’s Design Week in 2014.

MM: It would be so extraordinary to have this as a centerpiece of a room because you would really feel like you had flowers in your life—and joy in your life—at any moment. I think that’s one of the wonderful aspects of your work—that level of joy and discovery and moment of innocence when you see something for the first time and get that sense of history and personal reflection all together. Can you talk a little about what propelled you?

MW: Yeah, we follow the unexpected. Meaning that sometimes you see something for the first time and you are surprised by what it is. It’s something you recognize in a way, you understand it’s a chair, but it feels softer—and then it’s surprising because there is some innovation in it. And it’s surprising, it makes you happy.

We try to make works that are new but also at the same time you feel you can recognize them from the past—from your soul, from your family, from our culture. We do that in very different ways and this is one of them.

Crystal Fire by Wanders for Moooi Carpets, 2015.

MM: I think design as an art form, as a discipline, is so important because it does more than architecture—it truly reflects culture and can and should reflect culture.

MW:It should but it doesn’t always.

MM: It doesn’t always but it should, and I think it’s so important to commemorate who we are and where we are.

MW: This is really one of the most important subjects of my work. We’ve had one hundred years of modernism. We’ve had a few years of postmodernism; but I think if I look at the world, I look at my heart, if I read people’s minds, we are beyond postmodernism.

If I look to theater, if I look to art, if I look to poetry, I see we are onto something that is different….I would call it some kind of romantic humanism. It’s holistic, and I feel we are entering a new stage of culture. But if I look to design, strangely enough, designers are happily-ever-after back in modernism. After postmodernism they have gone back to modernism, and it’s weird to me. I don’t get it. I’m really fighting that notion and am really trying to make us understand that, yes, with design it’s very comfortable to be in modernism because it’s rational and we can explain everything; but it’s not where we should be. If we really want to support our culture, if we really want to step into the life we are living today, and we want to be relevant as an art form, then we have to find new territory.

Wanders’s installation at Friedman Benda includes large abstract figural mirrors such as Merrick, 2016, produced in an edition of eight.

MM: You’re with the gallery Friedman Benda in New York, and you have a show there now. What work are you showing?

MW: We go a long way back with Friedman Benda. Years ago we made a Crochet chair for them, for example.

MM: We’ve run that chair on the cover of MODERN. I believe the High Museum in Atlanta has one in its collection.

MW: It’s an amazing piece. We’ve been working with Friedman Benda over the years and we thought it was a nice moment to do a special presentation, a special exhibition. I’m super excited about it. There are some really cool things.

MM: Did you do pieces specifically for the show?

MW: Yeah, we have a few things that have been seen before, but most of the work is brand new. It’s a very diverse group of work. There is video art, there are furniture pieces, and there is sculpture, so it’s a very broad spectrum.

The signature version of Wanders’s Charles chair for Moooi, 2014, is called Composition 14.

MM: There’s an aspect of your work that may be more peculiar to Dutch design than to design coming out of other cultures but not unique to Dutch design, namely, that in your work—as in the Crochet chair —you take an old, old craft that was really women’s work and you make it something that is entirely contemporary. And you couldn’t do it without today’s technology and that’s true in the carpets too.

MW: We make new things, you know, but in connection to our past, to our culture. To me that’s super important. And whether in the past I find high art or I find stuff that my Grandma did, I think they are all very relevant, right? I love to play with these things, juxtapose them, and give them a new life. I think it adds to a piece. I think that if we did something super new, completely new (and we could), it would probably be very uninteresting. I mean it gets interesting because it’s already a part of us, we are connected to it. It’s like it resonates with our culture, with our heart. That is value to me. That is how a piece can live with people for a long time. A lot of works today are made for the future. The most important dogma of modernism is that the past is irrelevant to the future. So what does that mean for the things we create today?

MM: They’re obsolete the moment you make them.

MW: And that is exactly what this culture has done. We have created a throwaway society based on that fundamental dogma, and it’s something we cannot sustain, we cannot live that way.