Architecture

Doing Right by Wright

SAVING AMERICA’S ARCHITECTURAL TREASURES

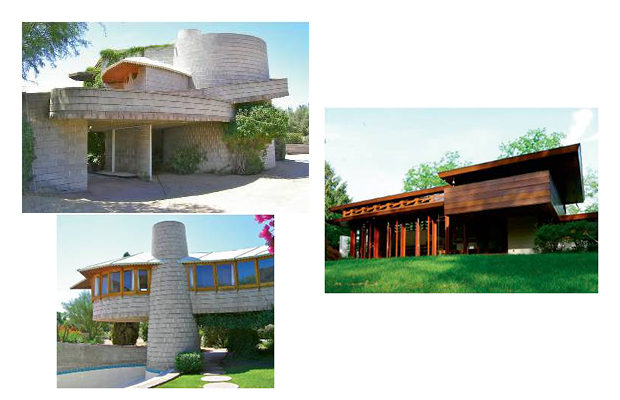

The David and Gladys Wright House in Phoenix, Arizona, shares its circular design plan with the Guggenheim Museum in New York, which it presages by six years.

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT is inarguably the most important American architect of the twentieth century, but that distinction has not always protected his legacy. A larger-than-life figure who lived to be ninety-one and completed nearly five hundred buildings in his seventy-five-year career, Wright moved from the Prairie school to his own self-defined organic design and defined American architecture for more than half a century. Today hundreds of thousands of tourists visit and admire the more than fifty Wright sites that are open to the public, but chances are they little realize that roughly one hundred of the architect’s buildings—one of every five built—have been destroyed.

The good news is that no Wright buildings have been demolished in the last forty years, thanks in a large part to the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy, the twenty-four-year-old organization that most recently worked tirelessly to save the dramatically situated earthquake-damaged Ennis House in Los Angeles, one of Wright’s masterworks. It had been put on the market by its nonprofit owner because the repair costs were too high and happily rescued in 2011 by Ron Burkle, who now owns it.

Not all Wright buildings are as fortunate. Several notable ones are at risk and require urgent intervention, most prominently, the David and Gladys Wright House in Phoenix, Arizona, which is described by architecture historian and Wright scholar Neil Levine as “one of the two or three most important existing and intact houses by Wright still in private hands.” Notable for its circular plan, which presages the Guggenheim Museum in New York by six years and is said to have influenced it, the David and Gladys Wright House stands in a desirable neighborhood on a sizable lot, making it especially vulnerable to demolition. It is a classic example of a Wright house that has fallen into the wrong hands. On the death of the original owners, the house was sold to a realtor—someone the family trusted and thought would care for it. But when that person took possession of the house, she quickly sold the Wright-designed carpet that came with it, never moved in, and resold the house to developers. Janet Halstead, the director of the Wright Building Conservancy says, “We pointed out to the developers that the house was one of the most important buildings of Wright’s late career. But they are making it difficult to show it.” The best scenario says Halstead would favor a preservation-minded individual to purchase the house. Short of that, the conservancy would settle for a sensitive lot split—subdividing the property into two parcels, one for the Wright house, which could possibly continue as a museum, and another where a new house could be built. Two recent articles about the house, have appeared in the New York Times, thus raising awareness of its legacy and plight. Commenting on the house’s dire situation, Levine says: “Had it not been in private hands and in such an ambiguous ownership position when I and my colleagues at the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy drew up the list of the ten to twelve most important Wright buildings for our World Heritage List nomination (soon to be presented to UNESCO) we would have certainly included it.”

UPDATE: As MODERN went to press, a full-price offer had been made on the house by an anonymous buyer, who plans to restore and preserve it.

The Bachman Wilson House in New Jersey is one of Wright’s Usonian houses.

Although the current owners have faithfully preserved and protected the Bachman Wilson House, upstream development has caused it to flood multiple times in the past five years.

Another endangered Wright house also linked to the Guggenheim, is the Bachman Wilson House in New Jersey. It is one of Wright’s Usonian houses and was built while he was working in New York on the Guggenheim. Its owners, Sharon and Lawrence Tarantino, have been more than dutiful stewards, going above and beyond what is expected of any Wright homeowner. As architects with experience preserving modern buildings, including a few of Wright’s, they have greatly improved the house since taking possession in 1988. They painstakingly researched such details as the red pigment of the concrete floors, among other things, to restore it to Wright’s original vision. Yet, in spite of their obvious talents and their loving touch, they cannot protect the house from what ails it most—the threat of flooding from upstream overdevelopment that has drastically altered the hydrology at the site, causing the house to flood not once but on several occasions in the past five years. With the blessing of the conservancy they plan to move the house when the right buyer with the right site comes along. Details about the house, including costs for moving and reassembling it, can be found on the website www.bachmanwilsonhouse.com.

Another threatened Wright building, not a residence but no less important, is the A. D. German Warehouse in Richland Center, Wisconsin, which bears the distinction of being Wright’s only warehouse and the only structure located in his birthplace. It is notable for its decorative Mayan-inspired frieze, a motif Wright would later explore in his western work. In August the Richland Center City Council voted against purchasing the German Warehouse and its surrounding properties but expressed support for its private acquisition and redevelopment. Larry Woodin, the president of the conservancy, says the building lends it itself well to reuse by multiple tenants who could share the space. A buyer is being sought.

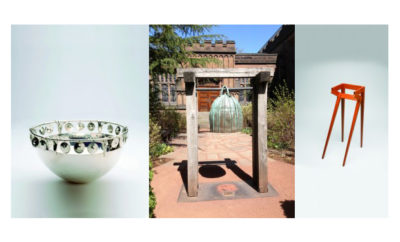

Although it sustained earthquake damage, the Ennis House in Los Angeles is among those saved by a preservation-minded owner.

The three buildings mentioned here are important not only as individual works of art but also for their connection to Wright’s greater body of work. The David and Gladys Wright House and the Bachman Wilson House, for example, contribute greatly to our understanding of the Guggenheim Museum—what Wright was doing at that time, what ideas he had brewing. And the German Warehouse provides an early glimpse of a Native American decorative motif that Wright would take up in such buildings as the Hollyhock House, one of his great residences.

With the announcement in September that the Wright archive has been acquired by the Museum of Modern Art and Columbia University and is moving to New York, greater access to Wright’s work will be had by a larger audience. Wright is famously thought of as a midwestern architect who later went out west. With the archive’s move to New York, it shifts the focus to his East Coast work in the nick of time, and it should build a greater appreciation for Wright’s surviving buildings, large and small.