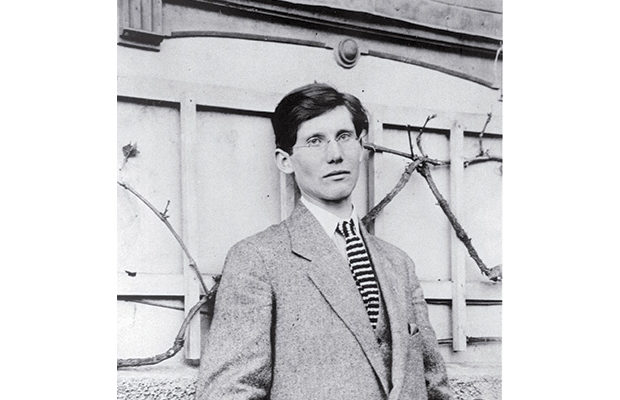

Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, c. 1910

Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, c. 1910

Feature

In Le Corbusier’s Footsteps

“For Jacob Brillhart, drawing is a way of seeing. Fresh from Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Brillhart determined that he would follow the time-honored tradition of a drawing trip. Later calling it “a slow grand tour for a young, restless architect,” he set out with his sketchbooks, pencils, and watercolors. Along the way, he became fascinated with what he would come to call “Le Corbusier’s early mysterious time of intellectual development and most specifically his early sketchbooks.” That early curiosity turned into a quest to follow the master as he traveled through Turkey, Greece, Italy, Spain, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany—both as an homage and as a way to see what Le Corbusier saw and learn from him. The following excerpt comes from Voyage Le Corbusier: Drawing on the Road (W. W. Norton), Brillhart’s new book about Le Corbusier’s own grand tours and the drawings they produced.”

— Beth Dunlop

Excerpted from Voyage Le Corbusier: Drawing on the Road

By JACOB BRILLHART

LE CORBUSIER [CHARLES ÉDOUARD JEANNERET] was a deeply radical and progressive architect, a futurist who was equally and fundamentally rooted in history and tradition. He was intensely curious, constantly traveling, drawing, painting, and writing, all in the pursuit of becoming a better designer. As a result, he found intellectual ways to connect his historical foundations with what he learned from his contemporaries. He grew from drawing nature to copying fourteenth-century Italian painting to leading the Purist movement that greatly influenced French painting and architecture in the early 1920s. All the while, he was making connections between nature, art, culture, and architecture that eventually gave him a foundation for thinking about design.

To learn from Le Corbusier’s creative search and to see how he evolved as an architect, one must understand where he started. He never attended a university or enrolled formally in an architecture school. His architectural training was mostly self-imposed and was heavily influenced by the teachings of his secondary-school tutor Charles L’Eplattenier, who taught him the fundamentals of drawing and the decorative arts at the École d’art in his hometown of La Chaux-de-Fonds in Switzerland.

The Acropolis, Athens, September 1911; reproduced in Voyage d’Orient, Carnet 3, p. 123. Pencil on paper.

Upon Jeanneret’s graduation from secondary school in 1907, L’Eplattenier encouraged him to leave behind the rural landscapes and broaden his world view by making a formal drawing tour through northern Italy. This pedagogy of learning to draw and learning through experience was likely influenced by the long tradition of the Grand Tour, a rite of passage for European aristocrats. Travel was considered necessary to expand one’s mind and understanding of the world. Architects, writers, and painters seized upon the idea, taking a standard itinerary across Europe to view monuments, antiquities, paintings, picturesque landscapes, and ancient cities.

The experience ignited in Jeanneret an enormous desire to see and understand other cultures and places through the architecture and urban space that shaped them. In Italy he expressed his first real interest in the built environment, primarily studying architectural details and building components.

Barn in landscape, Jura, Switzerland, October 15, 1902. Pencil and watercolor on paper, 4 3/4 by 6 1/4 inches.

Shortly after his return, he set off again, for Vienna, Paris, and Germany, becoming increasingly interested in cityscapes and urban design. Periodically he returned home to recharge and reconnect with L’Eplattenier. During his travels, the sketchbook emerged as Jeanneret’s premier tool for recording and learning, and drawing became for him an essential and necessary medium of architectural training. Between 1902 and 1911 he produced hundreds of drawings, exploring a wide range of subject matter as well as means and methods of recording.

Cathedral façade and details, Siena, Italy, 1907. Pencil, ink, and watercolor on paper, 10 by 13 5/8 inches.

With each trip he gained a broader view. As his interests shifted and expanded, so did his process of documenting what he saw. To his repertoire of perspective drawings of landscapes, beautifully detailed in watercolor, he added analytical sketches that captured the core of spatial forms and became a means of shorthand visual note taking. All the while, he frequently returned to old and familiar subjects to study them through different lenses in order to “see.”

Giuliano Gresleri, architectural historian and author of Les Voyages d’Allemagne: Carnets and Voyage d’Orient: Carnets (which include reproductions of Jeanneret’s notebooks during his travels to Germany and the East), said, “What distinguished Jeanneret’s journey from those of his contemporaries at the École and from the tradition of the Grand Tour was precisely his awareness of ‘being able to begin again.’ Time and again, this notion stands out in the pages of his notebooks. The notes, the sketches, and the measurements were never ends in themselves, nor were they a part of the culture of the journey. They ceased being a diary and became design.”

Tabernacle detail (design by Andrea Orcagna) at Orsanmichele, Florence. Pencil and watercolor on paper, 5 3/4 by 4 3/4 inches.

In 1911 Jeanneret completed the capstone of his informal education, a second drawing tour that Le Corbusier eventually coined his “Journey to the East” (actually the title of a book of essays and letters that he wrote during his travels there, published in 1966). By this time, he was interested in understanding more than just the monuments: he looked at the architecture and everyday culture. He had mastered the art of drawing through the daily practice of observing and recording what he saw. Through this rigorous exercise of learning to see, he had developed a vast tool kit of subject matter, means of authorship, drawing conventions (artistic and architectural), and media. More important, through drawing he came to understand the persistencies in architecture—color, form, light, shadow, structure, composition, mass, surface, context, proportion, and materials. As he reached Greece (halfway through his Journey to the East), Jeanneret not only proclaimed that he would become an architect but was working toward a theoretical position about design around which he could live and work….

Versailles, France, 1908–1909. Ink and watercolor on paper, 12 1/4 by 15 3/4 inches.

In the end, however, travel drawing was Jeanneret’s education and his rite of passage. Embodied in his sketchbooks is an incredibly comprehensive means of visual exploration and discovery. Though he never had a formal architectural education, his intense curiosity to understand the world through drawing and painting and writing is what made him such a dynamic architect, one from whom we can still learn today. The lessons he learned formed the basis of his general outlook and provided content for his later seminal text, Vers une architecture. They also prepared him to become Le Corbusier.

One expects most architects in training to go out and draw buildings. Jeanneret, however, was curious about everything. While his primary focus shifted from trip to trip, he drew flora, fauna, people, objects, art, patterns, and furniture, as well as landscapes, cityscapes, interior and urban space, facades, architectural and construction details, monuments, and everyday architecture. Nonetheless, each time period can be broadly defined by distinct interests and subjects of study. When learning to draw in La Chaux-de-Fonds, he looked primarily at the natural world, drawing landscapes, flora and fauna, geometries and patterns related to the decorative arts. During his first formal drawing trip, to Italy, he continued exploring the decorative arts by drawing the surface and ornament of building components—mainly objects as opposed to places.

German house, 1910; reproduced in Les Voyages d’Allemagne, Carnet 2,pp. 125–126. Pencil and watercolor on paper.

When he arrived in Vienna and Paris, his interest shifted to interiors, to medieval urbanism, and to cityscapes as landscapes. In Germany he studied public squares, urban spaces, and the iconic buildings that anchored them. By the time he set off on his Journey to the East, he had enlarged his attention to the culture and urban spaces of the entire city, as if he were seeing it from ten thousand feet above. Yet his youthful curiosities remained: he drew peasants’ houses, people, food, simple pots, plants, animals, insects, and furniture.

ALL IMAGES FONDATION LE CORBUSIER © F.L.C