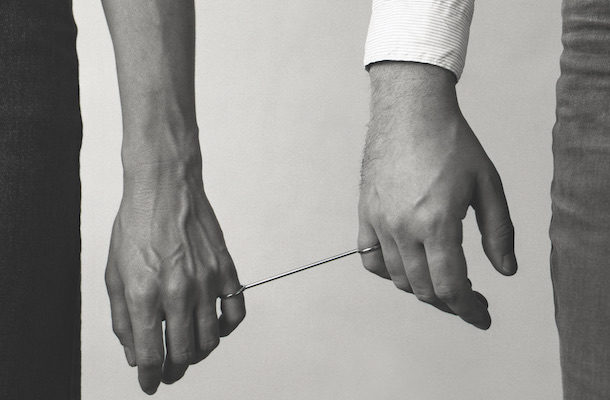

Ring für zwei Personen (Ring for Two Persons), Otto Künzli, 1980. OTTO KÜNZLI PHOTO.

Ring für zwei Personen (Ring for Two Persons), Otto Künzli, 1980. OTTO KÜNZLI PHOTO.

Feature

Two for the Show: Jewelry’s Power Couples

JEWELRY IS THE MOST INTIMATE ART FORM, characterized by a symbiotic relationship with the human body. It functions by touch, embracing one’s ears, neck, chest, wrists, and fingers. Jewelry is seductive. Not surprisingly, many jewelers fall in love with one another. In fact, some of the most notable jewelers of the past seventy years—including several of the field’s superstars—have chosen to marry. Might it be the allure associated with jewelry that attracts these artists romantically? Or simply a common aesthetic and shared passion? Whatever the reasons, making jewelry evidently makes for love. Some jewelry-making couples who cohabitate also collaborate, while others are amorous partners but create artworks autonomously. However one looks at it, the work they generate, either alone or together, would not be the same without the closeness of their relationships. Unlike contemporary jewelry couples, most of whom met in art school, mid-century modernist jewelers found their mates in distinctive ways.

Otto Künzli and Therese Hilbert

Therese Hilbert and Otto Künzli at their 2016 duo exhibition &: Hilbert & Künzli at the Gewerbemuseum, Winterthur, Switzerland. Miriam Künzli Photo.

Munich-based Otto Künzli and his wife, Therese Hilbert, although “alongside and with one another” for more than forty-five years, are aesthetically dissimilar. As Hilbert states: “Our work is, and always has been, very different in spite of all we have in common.” They were both born in Zurich in July 1948 (within three days of one another) and have consistently shared a like material sensibility. As children they each had a fascination for sharks’ teeth, which both avidly collected, just as they now collect stones—volcanic rocks in Hilbert’s case and prehistoric implements for Künzli. The couple met around 1965 at the Schule für Gestaltung in Zurich, where both were studying with legendary Swiss goldsmith Max Fröhlich. They began sharing their lives in 1971, marrying the following year and moving to Munich. They both enrolled at the Academie der Bildenden Künste, München, where they studied goldsmithing with Hermann Jünger, graduating in 1978. They have shown together periodically at galleries around the world. But until &: Hilbert & Künzli—their 2016 blockbuster exhibition at the Gewerbemuseum in Winterthur, Switzerland—their only duo museum presentation was at the Schmuckmuseum Pforzheim, in Germany, in 1979.

Fox by Otto Künzli, 2010. MDF and alkyl linoleum paint. Courtesy Gallery Funaki.

Künzli is one of the most radical jewelers and influential teachers in the field. He was among the first to question the very essence of jewelry—what it is, what it has been, what it means, and what it can be. Throughout his career, Künzli has made works that have become contemporary icons. He has a particular fondness for jewels that speak of love’s comforts as well as its complications, exemplified by a necklace comprising forty-eight interlocking gold wedding rings spanning the years 1881 to 1981, which he amassed by placing advertisements in Munich newspapers. Hilbert, meanwhile, addresses the charged confluence between submission and protection, gentleness and aggression, love and hate. Of her, Künzli has stated: “[Therese’s] works originate from a spirit of opposition between hard and soft—a dialogue between sensitivity and self-defense.” Although the two perpetually exchange ideas and discuss their activities, Hilbert requires privacy. In this regard Künzli notes: “Only too often has a piece been left half-finished because I poked my nose in at the wrong time.”

Stern (“Star”) by Therese Hilbert, brooch, 1985. Silver, stainless steel. Otto Künzli Photo.

There are many other noteworthy couples working in jewelry today, such as Germans Norman Weber and Christiane Förster, Georg Dobler and Margit Jäschke, and Bettina Dittlmann and Michael Jank; Italians Annamaria Zanella and Renzo Pasquale; Israel-born Attai Chen and his German-Iranian partner, Carina Shoshtary; and Stockholm-based Adam Grinovich and Annika Pettersson, and Beatrice Brovia and Nicolas Cheng. Brovia and Cheng, like the others, maintain separate practices, but since 2011 have collaborated on a joint project that focuses on interdisciplinary material research and craft discourse through installations, objects, and jewelry. All in all, whether by a common intellect and aesthetic sensibility, compatible theoretical bent, physical attraction, or simply the mystery of love, one fact is certain: couples who make jewelry turn each other on.

Toni Greenbaum is an art historian specializing in twentieth- and twenty-first-century jewelry and metalwork.

This article has been updated to correct two errors that appeared in our Summer print issue: the proper photograph is shown with the discussion of Sam and Carol Kramer; and the caption to the image of Gijs Bakker and Emmy van Leersum’s Clothing Suggestions has been corrected.