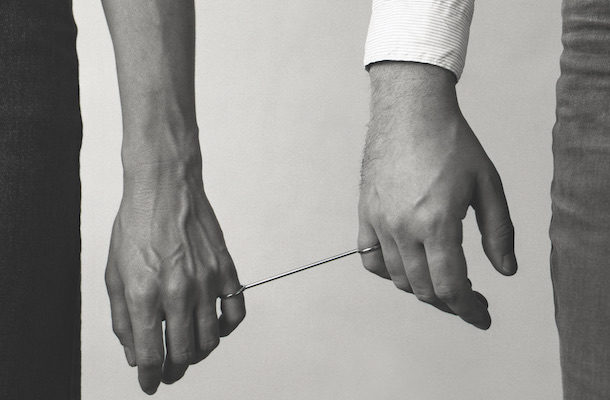

Ring für zwei Personen (Ring for Two Persons), Otto Künzli, 1980. OTTO KÜNZLI PHOTO.

Ring für zwei Personen (Ring for Two Persons), Otto Künzli, 1980. OTTO KÜNZLI PHOTO.

Feature

Two for the Show: Jewelry’s Power Couples

JEWELRY IS THE MOST INTIMATE ART FORM, characterized by a symbiotic relationship with the human body. It functions by touch, embracing one’s ears, neck, chest, wrists, and fingers. Jewelry is seductive. Not surprisingly, many jewelers fall in love with one another. In fact, some of the most notable jewelers of the past seventy years—including several of the field’s superstars—have chosen to marry. Might it be the allure associated with jewelry that attracts these artists romantically? Or simply a common aesthetic and shared passion? Whatever the reasons, making jewelry evidently makes for love. Some jewelry-making couples who cohabitate also collaborate, while others are amorous partners but create artworks autonomously. However one looks at it, the work they generate, either alone or together, would not be the same without the closeness of their relationships. Unlike contemporary jewelry couples, most of whom met in art school, mid-century modernist jewelers found their mates in distinctive ways.

Helen Britton and David Bielander

Helen Britton and David Bielander in their Munich studio, 2017. Dirk Eisel and Corinna Teresa Brix Photo.

Australian Helen Britton and her Swiss-born husband, David Bielander, were brought together by forty chickens. Around 2000, while both were students at the Academie der Bildenden Künste, München, they met at a school dinner where the dough-wrapped poultry was being roasted in an underground pit. They’ve shared their lives ever since, fifteen of those years in a joint Munich workshop with Japanese jeweler Yutaka Minegishi. All three work in the same studio—one spacious by European standards—allowing the trio to exchange ideas but still maintain their autonomy. Although all three possess common attitudes toward jewelry’s ever-expanding parameters, they hold different aesthetic positions on whether to use found objects or natural materials, carving or assemblage. Connected by a mutual fascination with one another’s disparate cultures and nostalgia for their respective birth homes, Britton, Bielander, and Minegishi additionally share a love of food, music (Bielander and Minegishi are both seasoned musicians, often performing together), and flea markets. When Britton and Bielander were married in 2012, Minegishi was their sole attendant. Although they have rarely shown as a group, in 2015 Galerie Rosemarie Jäger in Hochheim, Germany, featured the three of them in its Couples in Jewelry series, titling the exhibition The Bride, The Groom, and The Best Man.

Cardboard series bracelets by David Bielander, 2015. Patinated silver, white gold. Dirk Eisel Photo.

While differing stylistically, Bielander’s and Britton’s respective practices both address transformation, questioning what is real as opposed to artificial. Being a meticulous thinker, Britton seeks to organize the chaos of urban environments into some semblance of order. She converts the visual cacophony of construction sites and the detritus of industry, along with most cities’ paradoxically persistent thrusts of nature, into colorfully dense assemblages of both appropriated and fabricated elements, much of it inspired by costume jewelry, which she adores. Bielander, on the other hand, inverts our sense of perception with trompe-l’oeil jewels and objects, such as “sausage” necklaces made up of elements cut from bentwood chairs, “cardboard” bracelets and “paper” bags fabricated from precious metals, and “slugs” of patinated silver.

Helen Britton amidst an array of her brooches, 2016. Dirk Eisel Photo.

There are many other noteworthy couples working in jewelry today, such as Germans Norman Weber and Christiane Förster, Georg Dobler and Margit Jäschke, and Bettina Dittlmann and Michael Jank; Italians Annamaria Zanella and Renzo Pasquale; Israel-born Attai Chen and his German-Iranian partner, Carina Shoshtary; and Stockholm-based Adam Grinovich and Annika Pettersson, and Beatrice Brovia and Nicolas Cheng. Brovia and Cheng, like the others, maintain separate practices, but since 2011 have collaborated on a joint project that focuses on interdisciplinary material research and craft discourse through installations, objects, and jewelry. All in all, whether by a common intellect and aesthetic sensibility, compatible theoretical bent, physical attraction, or simply the mystery of love, one fact is certain: couples who make jewelry turn each other on.

Toni Greenbaum is an art historian specializing in twentieth- and twenty-first-century jewelry and metalwork.

This article has been updated to correct two errors that appeared in our Summer print issue: the proper photograph is shown with the discussion of Sam and Carol Kramer; and the caption to the image of Gijs Bakker and Emmy van Leersum’s Clothing Suggestions has been corrected.