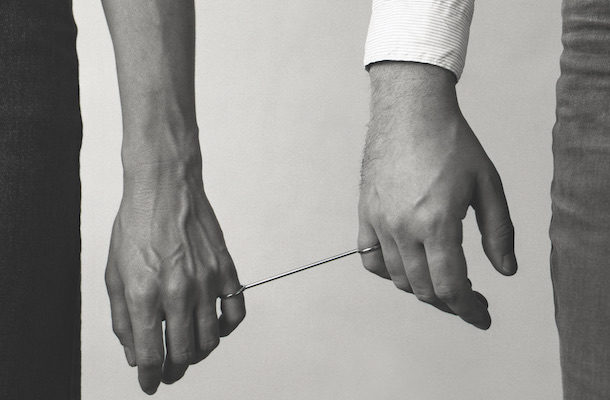

Ring für zwei Personen (Ring for Two Persons), Otto Künzli, 1980. OTTO KÜNZLI PHOTO.

Ring für zwei Personen (Ring for Two Persons), Otto Künzli, 1980. OTTO KÜNZLI PHOTO.

Feature

Two for the Show: Jewelry’s Power Couples

JEWELRY IS THE MOST INTIMATE ART FORM, characterized by a symbiotic relationship with the human body. It functions by touch, embracing one’s ears, neck, chest, wrists, and fingers. Jewelry is seductive. Not surprisingly, many jewelers fall in love with one another. In fact, some of the most notable jewelers of the past seventy years—including several of the field’s superstars—have chosen to marry. Might it be the allure associated with jewelry that attracts these artists romantically? Or simply a common aesthetic and shared passion? Whatever the reasons, making jewelry evidently makes for love. Some jewelry-making couples who cohabitate also collaborate, while others are amorous partners but create artworks autonomously. However one looks at it, the work they generate, either alone or together, would not be the same without the closeness of their relationships. Unlike contemporary jewelry couples, most of whom met in art school, mid-century modernist jewelers found their mates in distinctive ways.

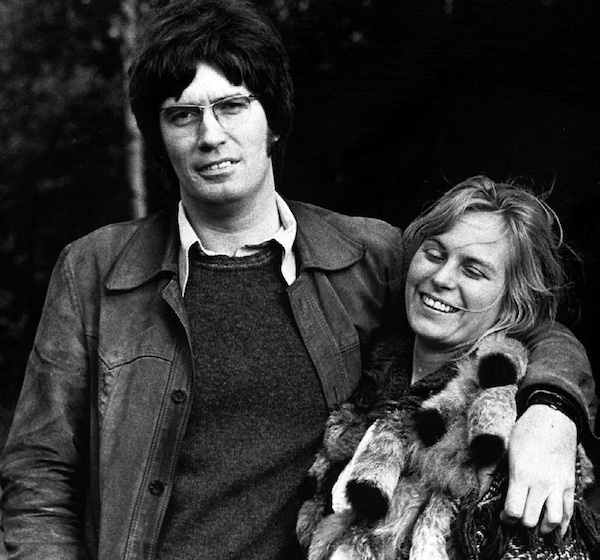

David Watkins and Wendy Ramshaw

David Watkins and Wendy Ramshaw at Hampstead Heath, 1974. Courtesy Toni Greenbaum.

Neither David Watkins nor Wendy Ramshaw set out to pursue jewelry, and, in fact, neither formally studied the discipline. Watkins was a jazz musician and composer, before adding sculpture, and later jewelry, to his repertoire. As a jeweler, he is best known for large, rigid, technologically advanced neckpieces and bracelets that embody the rhythmic syncopations of bebop while defining the spatial relationship between the human figure and its immediate surroundings. As a designer, he is noted for special-effects models used in the production of the 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey and medals for the 2012 London Summer Olympics. Ramshaw is famous for her lathe-turned and multi-layered ring sets—inspired by the machinery in Watkins’s studio—and architectural iron gates, such as those in London’s Hyde Park.

Three views of Her Knight (from Room of Dreams) by Wendy Ramshaw, 2002. Set of sixteen rings in yellow and white gold on an anodized aluminum stand. George Gammer Photo

Ramshaw and Watkins met around 1961 at the University of Reading in England, where Ramshaw, who originally concentrated on textile design and illustration, introduced Watkins to applied art. They married in 1962, and Ramshaw, who was fabricating inexpensive copper and brass jewelry for local shops at the time, began to experiment with the acrylic and spray paint she found in Watkins’s studio. The following year the couple had their first two-person show, for which Watkins made quasi-figurative sculptures in wood and metal, and Ramshaw constructed stabiles and painted abstract floral images. Within the year they also embarked on the first of two commercial ventures, Optik Art Jewellery, consisting of screen-printed acrylic adornments inspired by the op art movement in painting and progressive clothing of couture designers such as Yves Saint Laurent and Paco Rabanne.

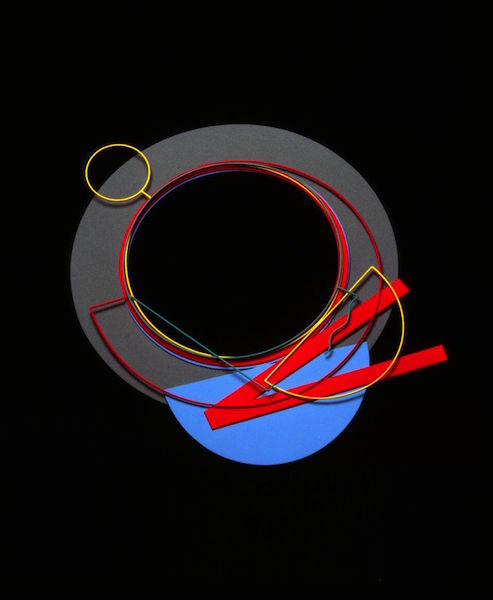

Diver by David Watkins, 1985. 4-part combination neckpiece, neoprene over wood, steel. David Watkins Photo.

Around 1965, after Optik Art Jewellery suspended operations, Watkins and Ramshaw established Something Special Ltd., for which Ramshaw made necklaces from sizable, colored wood beads that were carried by the boutiques of fashion icons, such as Mary Quant, as well as “flat pack” paper jewelry—meant to be assembled by the purchasers—which she designed with Watkins. Although Something Special closed around 1967, the flat pack concept was revisited in 2000 with their book The Paper Jewelry Collection: Easy To Wear and Ready To Make Pop Out Artwear. By the early 1970s Watkins and Ramshaw had embarked on their own independent careers as studio jewelers, although, over the years, they have been the subject of several two-person museum exhibitions. Distinguished British jewelry historian Graham Hughes saw fit to honor them in his 2009 book David Watkins Wendy Ramshaw: A Life’s Partnership.

There are many other noteworthy couples working in jewelry today, such as Germans Norman Weber and Christiane Förster, Georg Dobler and Margit Jäschke, and Bettina Dittlmann and Michael Jank; Italians Annamaria Zanella and Renzo Pasquale; Israel-born Attai Chen and his German-Iranian partner, Carina Shoshtary; and Stockholm-based Adam Grinovich and Annika Pettersson, and Beatrice Brovia and Nicolas Cheng. Brovia and Cheng, like the others, maintain separate practices, but since 2011 have collaborated on a joint project that focuses on interdisciplinary material research and craft discourse through installations, objects, and jewelry. All in all, whether by a common intellect and aesthetic sensibility, compatible theoretical bent, physical attraction, or simply the mystery of love, one fact is certain: couples who make jewelry turn each other on.

Toni Greenbaum is an art historian specializing in twentieth- and twenty-first-century jewelry and metalwork.

This article has been updated to correct two errors that appeared in our Summer print issue: the proper photograph is shown with the discussion of Sam and Carol Kramer; and the caption to the image of Gijs Bakker and Emmy van Leersum’s Clothing Suggestions has been corrected.